TRUE FORGIVENESS NEEDS CLOSURE

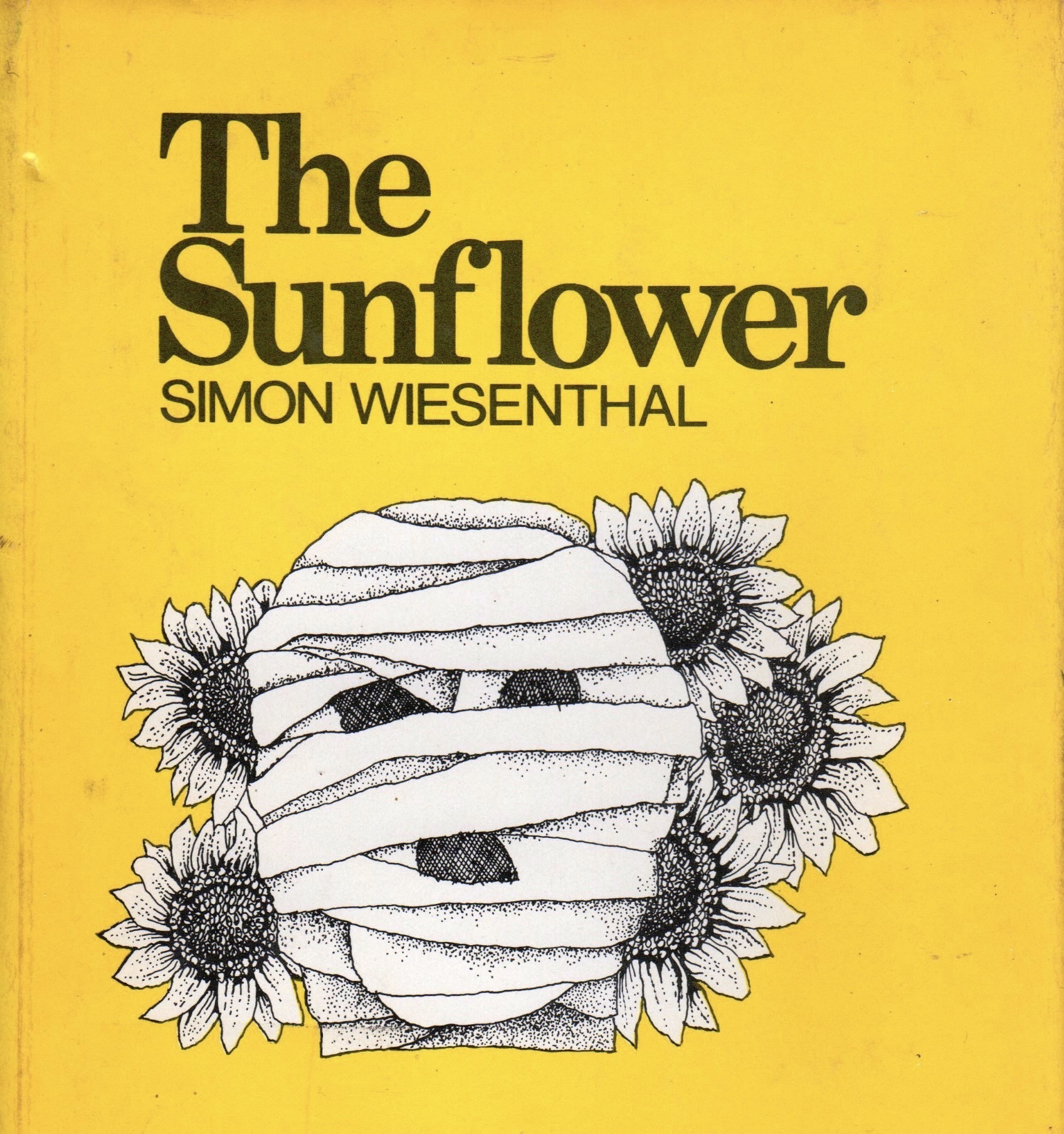

In 1976, the famous Holocaust survivor and Nazi-hunter Simon Wiesenthal published a small book called The Sunflower.

The book was inspired by a troubling and evocative memory that had plagued Wiesenthal ever since the Second World War. In 1943, while imprisoned at Janowska concentration camp on the outskirts of Lwow, Wiesenthal was suddenly spirited to the bedside of a dying 22-year-old SS soldier, Karl Seidl, who had told nurses to “bring him a Jew!”

Wiesenthal found the dying soldier wrapped in bandages covering his entire face, with only holes for his mouth, nose and ears.

Seidl spoke to Wiesenthal at great length. He described his idyllic childhood as a catholic altar boy from a loving non-Nazi home, and then spoke about his Nazi career, including his active involvement in the murder of hundreds of Jews whom he had burned alive and shot in cold blood. Now, as he lay dying, he was haunted by these heinous crimes, and felt compelled to offer a full confession to a Jew, and to obtain forgiveness from a Jew.

I am left here with my guilt. In the last hours of my life you are here with me. I do not know who you are, I only know that you are a Jew and that is enough. I know that what I have told you is terrible. In the long nights while I have been waiting for death, time and time again I have longed to talk about it to a Jew and beg forgiveness from him. Only I didn’t know if there were any Jews left. I know that what I am asking is almost too much for you, but without your answer I cannot die in peace.

Wiesenthal sat and listened to Seidl, but said absolutely nothing in response and then left him. Later that night the SS murderer died. Years later Wiesenthal went to visit Seidl’s mother to find out whether the dying Nazi’s description of his childhood had been accurate or overly idealized.

Seidl’s mother turned out to be a fine, upstanding woman, and she told Wiesenthal her son had been a normal, caring, responsible young man who was absolutely incapable of cold-blooded murder. Once again Wiesenthal was silent, this time so as not to reveal what he had heard from her son about his evil violence against Jews in Poland.

But the experience haunted him. As the years went by, Wiesenthal began to wonder: had he done the right thing?

Was my silence at the bedside of the dying Nazi right or wrong? This is a profound moral question that challenges the conscience of the reader of this episode, just as much as it once challenged my heart and mind.

In the first edition of The Sunflower, Wiesenthal reproduced the responses of ten people to whom he had posed the question. Ultimately this number increased to 53 men and women, whose responses appeared in subsequent editions.

The reactions were from a wide range of people, including Christians and Jews, Buddhists and atheists; they came from the Dalai Lama and Deborah Lipstadt, from Cardinal Franz König of Austria and Abraham Joshua Heschel, from a former West German justice minister and from a survivor of nineteen years in Chinese labor camps.

And while the answers varied, many of those who responded felt – as Wiesenthal himself had felt – that they could not forgive someone for a crime that had not been perpetrated directly against them.

This week, as I reflected on one of the most enduring puzzles of Joseph’s 22-years in Egypt away from his family, I was reminded of The Sunflower, and the answer I would have given Simon Wiesenthal had he asked me the question.

Why did Joseph not just reveal himself to his brothers as soon as he saw them, and get it over with? And although the brothers were the guilty party in this entire saga, is it not true to say that Joseph also bore some responsibility for his father’s misery? After all, are we to believe that he had never once had the opportunity to send a message home to his father, to let him know he was still alive? Certainly, as viceroy of Egypt, he could easily have been in touch. He may not to have been to blame for his father’s despair, but he was certainly not blameless.

In Maimonides’ laws of repentance (2:4) he informs us that atonement for sin requires more than just remorse. Although being sorry for what you’ve done is certainly important as an initial step, true teshuvah needs more than that – it requires a total character overhaul, so that one can say, “I am no longer the person who committed the sin; I am a totally different person.”

Maimonides even suggests (2:1) that the only way to know if one’s atonement has been successful is to find oneself in similar circumstances to those of the original sin, and this time to desist from sinning.

Had Simon Wiesenthal asked me for my response, I would have said that while Karl Seidl was clearly sorry for what he had done, he was on his deathbed, and it seems unlikely he would have been so remorseful had he not been dying. In full health he might well have killed thousands more Jews. In which case forgiveness has no meaning.

Just as Seidl’s confession was the empty plea of a dying, scared man, Wiesenthal’s forgiveness would also have been hollow and superficial.

This might explain Joseph’s decision to refrain from revealing himself to his brothers, and even from sending a message to his father at some point earlier on.

Joseph knew his predicament was no accident, and when he saw his brothers, he realized that in order for the plan to unfold correctly, it had to all fall into place properly. He could have magnanimously forgiven his brothers immediately, and in that situation, needing him for food, and shocked at his rise to such a powerful position, they would have gratefully welcomed that forgiveness.

But Joseph also knew that this would not be enough. In order to draw a line under their monstrous behavior they needed to be confronted with their sin, and not repeat it.

It was for this reason that Joseph orchestrated events so carefully, arranging for Benjamin to be suspected of thievery and taken away from his father. How would the brothers react? Would they repeat their sin?

But this time the brothers acted differently. Judah stepped forward and said to Joseph, “Spare our brother, and send him back to his father; rather take me in his place.” Only then was Joseph able to reveal his true identity, and only then could his brothers be properly forgiven.

Joseph also knew that Jacob wanted what was best for his children, and would not want his sons to have unfinished, unfinishable business. If this meant not seeing or hearing from his beloved son until that outcome was possible, Joseph knew Jacob would not just accept it, but would be happy he had been part of a process that allowed his children to reclaim their self-esteem.

In the final analysis, forgiveness amounts to nothing if it is not accompanied by true closure.

Rabbi Dunner together with Nazi-hunter Simon Wiesenthal in his Vienna, Austria, office – February 1998.