GROUNDHOG DAY AND THE JEWISH EXPERIENCE

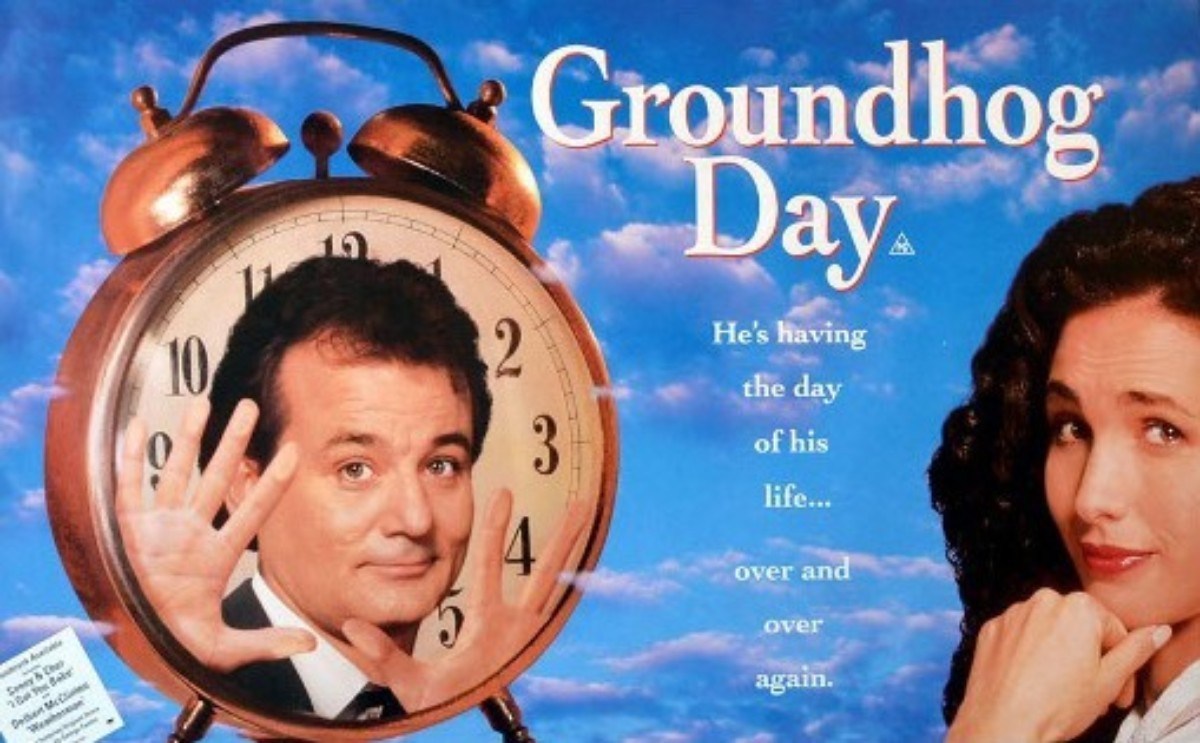

You may recall the 1993 movie Groundhog Day, starring Bill Murray and Andie MacDowell.

The premise of the movie is simple. Murray is Phil Connors, a TV weatherman assigned to cover an annual Groundhog Day event, and somehow finds himself caught in a time loop, reliving the same day over and over again.

The main thrust of the movie was an examination of what someone might do if they had the opportunity to correct their mistakes and missteps, and turn their life into a perfectly polished product, a fully-finished article with no flaws.

It has been calculated that Murray’s character repeated Groundhog Day 12,395 times during the movie, although we only get to see 38 of those days on-screen. Just to put that into perspective, 12,395 days is two weeks short of 34 years. During that time Phil Connors evolves from a selfish, self-centered narcissist into a kind, thoughtful person who can fluently recite French poetry and play piano, while saving people’s lives and acting selflessly.

And while the fact that no aspect of the day can change until he has somehow redeemed himself is presented as a curse, the predictability of each day from dawn to nightfall is his salvation. He knows exactly what is going to happen every minute of the day, with every detail fixed in a familiar montage of moving parts. The only variable is his reaction to those details and events. They will happen regardless of his response, while his attitude towards them and how he responds is up to him.

Every year at Passover we experience the Jewish religion’s version of Groundhog Day. We call it Seder Night – the annual event that commemorates the founding of the Jewish nation.

Like Groundhog Day in the eponymous movie, the timetable on Seder night is governed by a prescriptive schedule, unchanged for over a millennium.

The original Seder script was finalized during the Second Temple period, and the script we use closely follows the version created at that time. But the actual text we use – what we call the “

Every year we sit down to the Seder – we begin with Kiddush, then the Seder leader washes his hands without a blessing, we all eat a vegetable dipped in salt water, we split the middle matzah, and this goes on in hundreds of thousands of homes across the world, and has done for more than 1,000 years – all using the exact same formula. Millions of seders in every fathomable location and setting.

But just as no two Groundhog Days in the movie were ever the same, no two Seders have ever been the same. Every aspect at every Seder has followed the formula set out in the Haggadah, and we all use the exact same Haggadah, and yet, in spite of that, every Seder is different.

In the

Our challenge as those who attend the Seder is to use the familiar paraphernalia and guidelines and turn it into a unique Seder experience that improves every year. The familiar pattern becomes a platform for a better and more meaningful experience, so that in our Pesach Seder Groundhog Day experience we improve and

And actually, it is a perfect microcosm of our Jewish faith identity. The Torah is a flawless book, a gift from God to His Chosen People, the ultimate vehicle for self-improvement and for carrying out God’s mission. It is immutable. It is unchangeable.

And yet, when Moses was transported to the Beit Midrash of Rabbi Akiba he found that he could not understand one word of the Torah discussion going on there. Crestfallen, he needed to be reassured by God that the Torah taught by Rabbi Akiba was the same Torah received by Moses at Mount Sinai.

In the early twentieth century Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik published his seminal work on Maimonides, Chiddushei Rabbeinu Chaim HaLevi al HaRambam, in which he reconciled contradictory passages in Maimonides’ magnum opus Mishneh Torah. I have a feeling that if Maimonides would have read Rabbi Soloveitchik’s work he would have struggled to reconcile his own words with the incredibly novel explanations contained therein.

But in the same way that God reassured Moses that Rabbi Akiba’s Torah was the same Torah, Rabbi Soloveitchik’s explanations of Maimonides are branches of the Maimonides tree – and it does not end there. Maimonides’ own work similarly rearranged the Talmud, which was, in turn, a work produced by the Talmudic sages to unpack the Torah, so that it could be practiced and preserved as history unfolded.

That is the wonder of Judaism – it is Groundhog Day, the same, and yet every day is different, allowing us to hone it and perfect it, while at the same time preserve it and cherish it as our authentic heritage and tradition.

There is a wonderful Midrash that explores a remote facet of the Exodus odyssey. When the Jewish people departed Egypt, they took the little they had with them for the journey: some scraps of unleavened bread, a few animals for transportation, and the clothes on their back.

Miraculously the clothes they wore as they left Egypt never wore out, going on to last them throughout their years in the wilderness. The shrouds we use when burying

What a wonderful metaphor for Judaism. The clothes we were wearing when we became a nation are the eternal vestments of our identity – never wearing out, reminding us who we are and where we come from. And ultimately, they accompany us on our final journey. We wrap ourselves in our Groundhog Day, and at the same time we live out our individual lives.

Egyptian culture was the exact opposite. They mummified their dead. They were experts at preserving remains. Because in their mind all that mattered was ossifying the past. There was no development. No growth. Even as the culture thrived it was already, destined for oblivion.

Which brings me to Yizkor, the memorial service we recite on the last day of festivals and on Yom Kippur. Yizkor is not about the deaths of the people we loved. Our loved ones are not dead if they are the clothes that we wear as we go through life after they are gone. And if we wear those clothes – our parents, our grandparents – as life unfolds, not only do they never wear out, but we improve upon them.

It is possible that if our parents saw us five years, ten years, fifty years after they died, they would be like Moses sitting at the back of Rabbi Akiba’s Beit Midrash, or Maimonides reading Rabbi Soloveitchik’s book. And yet, we could tell them – we are your Groundhog Day, and we have taken that script, that model, and have improved it and perfected

Yizkor is not a morbid moment. It is our moment to revisit the Seders we had with our parents, and they had with theirs. We are not expected to remember that they died. Rather, Yizkor is a time to remember how they lived, so that we can emulate their faith and their goodness.

In March 1955, Albert Einstein was asked to eulogize his closest friend, Swiss engineer Michele Besso. Shortly afterwards he wrote a letter to the Besso family, to express his sorrow but at the same time to convey his sense of closeness to his dear departed friend, which had barely diminished.

“Now he has departed from this strange world a little ahead of me,” Einstein wrote. “But that means nothing. People like us, who believe in physics, know that the distinction between past, present and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.”

(Delivered as the Yizkor Drasha by Rabbi Pini Dunner at Beverly Hills Synagogue on the last day of Pesach, April

Image: movie poster for Groundhog Day, 1993 (public domain)