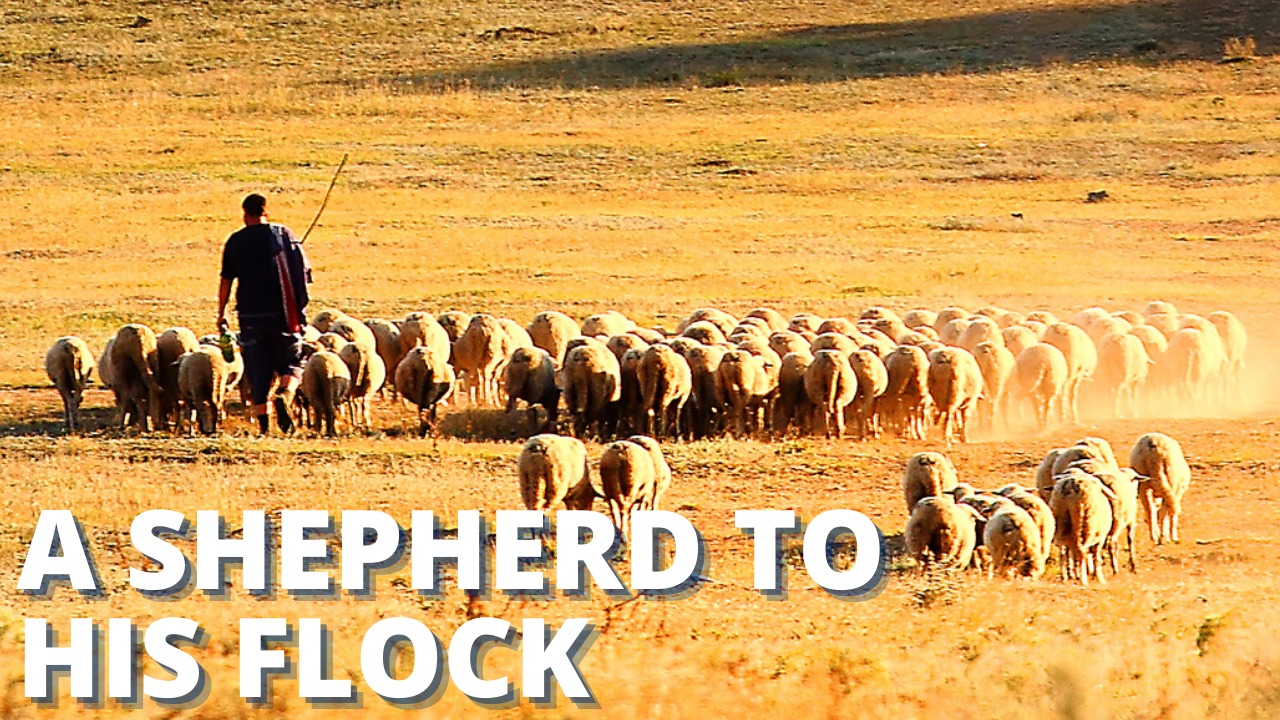

A SHEPHERD TO HIS FLOCK

Let me begin by sharing a question from the acclaimed author and lecturer, Alison Armstrong: “What if greatness is as simple as reliably being that quality day in and day out, even under stress?”

For James Clear, author of No.1 New York Times bestseller Atomic Habits, the answer is clear – true greatness is always measured in terms of consistency: “Meditating once is common; meditating daily is rare. Exercising today is simple; training every week is simply remarkable. Writing one essay doesn’t mean much; writing every day makes you a hero.”

But truthfully, this is a confounding idea. After all, when it comes to measuring greatness, what about talent? What about charisma? What about brilliance? What about wisdom? Surely these attributes are the foundation of true greatness?

One of the greatest rabbis of all time was Rabbi Moses Maimonides (“Rambam”; 1132-1204). He was the author of numerous rabbinic works; a superlative scholar of Torah, philosophy and science; leader of the Egyptian Jewish community; court physician to Sultan Saladin; and mentor and counselor to countless rabbis and communities across the Jewish world.

Maimonides regularly corresponded with his colleagues and students, often sharing intimate thoughts and personal experiences. His letters offer a revealing glimpse into the life of this extraordinary individual, but there is one letter that stands out.

In 1199, Rambam wrote to Samuel ibn Tibbon (c.1150-c.1230), his dear friend from Marseilles, France. Ibn Tibbon had expressed an interest in visiting him, but Rambam discouraged him from embarking on the trip, and explained that it would be impossible for them to spend any time together, as his overstretched daily schedule simply would not permit it.

“This is what I do each day” he wrote to Ibn Tibbon. “I live in Fustat, and the Sultan resides in Cairo – about 4 miles distance from each other. My duties to the Sultan are very heavy. I need to visit him each weekday, early in the morning. And when he or any of his children, or any of his wives, are unwell, I cannot leave Cairo as I need to stay in the palace for most of the day. Often, one or two royal officers are also sick, and I have to look after them. For this reason, as a rule, I go to Cairo very early, and even if nothing unusual happens I don’t return to Fustat until the afternoon. By then I am almost dying with hunger, but my office is already full of people – Jews and Gentiles, nobles and commoners, judges and bailiffs, friends and enemies: a real mixed multitude – all of them waiting for me to return.

“I dismount my horse, wash my hands, and ask my patients to bear with me as I eat a little – often this will be the only meal I have all day. After that I attend to my patients and write prescriptions for their various ailments. Patients come and go until evening, and sometimes for another two hours into the night. I talk to them all and prescribe medication, even as I’m lying down from sheer fatigue. By nightfall I am so exhausted I can hardly speak.

“As a result, no Jewish person can meet me privately, except on Shabbat, when the whole congregation, or most of them, come to me after morning services, and I tell them what needs to be done in the coming week. We study together until noon, and then they leave. Some of them come back and learn with me following afternoon services until evening prayers. That’s how I spend every Shabbat. And, just to be clear, what I have told you is only a part of what you would see if you came to visit.”

The most striking aspect of the letter is how this distinguished author of the most seminal rabbinic works on Jewish law and philosophy, a man who literally shone with intellect and wisdom, spent his day, from early morning until late at night, following a schedule that would have been tough enough had it been just one day each week. But it was every day.

While Rambam’s greatness was undoubtedly enhanced by his talents, charisma brilliance, and wisdom, the foundation of his greatness was doggedness – his relentless dedication to a daily schedule that was as rigorous as it was predictable.

The Midrash Yalkut Shimoni (169:7) picks up on the rather curious description of Moses as a shepherd (Ex. 3:1): וּמֹשֶׁה הָיָה רֹעֶה אֶת צֹאן יִתְרוֹ חֹתְנוֹ – “Moses pastured the flocks of Jethro, his father in law.”

The Midrash uses this verse as the trigger for a question: how does God test the righteous to see if they are great? God judges them by seeing how they do as shepherds, says the Midrash. The idea seems to be, if you can take good care of a flock of sheep, you must be a great person. Bottom line: Moses was very great because he was a good shepherd.

That’s the kind of statement which sounds cute, but doesn’t stand up to closer scrutiny. Think about it – who was Moses? He was a prince in Egypt who abandoned his privilege to save a Jewish slave being beaten. He later intervened after seeing two Jews fighting and got himself into trouble. Forced to flee Egypt, he arrived in Midian and saw Jethro’s daughters being unfairly treated. Again, he intervened to sort things out when no one else would.

Each of these events portrays Moses as a great man, standing up for the underdog even though he had nothing to gain and everything to lose. So why does the Midrash propose the idea that his greatness was derived from the fact that he was a good shepherd?

The point, I think, is simple. What makes someone great is not some one-off act of heroism, however remarkable that act may be. Rather it is a daily commitment to caring for and tending to one’s flock, come rain or shine. For forty years, every day – from early morning to late night – Moses was always there for his flock: dependable, reliable, responsible, and consistent.

And so, in answer to Alison Armstrong’s question: yes, it’s true – “greatness is as simple as reliably being that quality day in and day out, even under stress.”