WHEN GOD’S FIRE BURNS WITHIN

There’s a section of Parshat Eikev that is familiar to all of us who pray the Shema every day, twice a day: it’s the second paragraph of Shema, beginning with the words וְהָיָה אִם שָׁמֹעַ.

But while parts of it are very positive, with God promising wonderful things to us if we follow the Torah’s directives, there is a part of this passage that is not so pleasant: וְחָרָה אַף־ה בָכֶם וְעָצַר אֶת־הַשָּׁמַיִם וְלֹא־יִהְיֶה מָטָר וְהָאֲדָמָה לֹא תִתֵן אֶת־יְבוּלָהּ וַאֲבַדְתֶם מְהֵרָה מֵעַל הָאָרֶץ הַטּוֹבָה אֲשֶר ה נֹתֵן לָכֶם — If you don’t follow God’s precepts, the Torah warns, “Then God’s anger will burn against you, and He will close up the heavens so there will be no rain, and the ground will not give its produce – and you will quickly die from upon the good land that God is giving you.”

The key words in this pasuk are: וְחָרָה אַף־ה בָכֶם – God’s anger will burn against you. Really? Burning anger? Respectfully, isn’t ‘burning anger’ a petty human characteristic? On the face of it, it seems—for want of a better word—ungodly. So how do we explain it?

This isn’t the first time we see this phrase. Back in Shemot, at the Burning Bush, God asks Moshe to lead the Jewish people out of Egypt. But Moshe turns Him down — not once, but over and over: I’m not worthy. They won’t believe me. I can’t speak well.

Finally, he says outright: שְׁלַח נָא בְּיַד תִּשְׁלָח — do you know what, just send someone else! He sounds like a teenager who is being asked to clean his room. Excuses. Deflections. And ultimately, deliberate evasion. Send someone else, because I’m not going!

And that’s when the Torah tells us: וַיִּחַר אַף ה’ בְּמֹשֶׁה – God’s anger burned against Moshe. That’s the apparent meaning of the words – God flew into a rage, and then Moshe backs down. Immediately afterwards, Moshe agrees to go, and off he goes… and he went on to become the best leader the Jews ever had.

But the Kotzker Rebbe gives us a completely different reading — and it changes everything. In fact, it’s sensational. The בְּ in the word בְּמֹשֶׁה doesn’t mean “against,” he says. Instead, it means inside. וַיִּחַר אַף ה’ בְּמֹשֶׁה — Hashem’s burning passion, His love for the Jewish people, His pain at their suffering, His urgency to redeem them — suddenly entered Moshe.

Until that moment, the slavery in Egypt hadn’t really penetrated Moshe’s kishkes. He knew it in his head, but he didn’t feel it in his core. Now, after his encounter with God – finally! – it was inside him.

And once it was in him, everything changed. The mission God had assigned him became who he was. Twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, Moshe was the shepherd of his people — their advocate, their protector, their voice. Even if he wasn’t worthy. Even if he wasn’t particularly articulate. Even if there were others who could do the job.

Real life is like that too. A mother has a sick child. She doesn’t say: “I’m not the right person to take him to the ER, they won’t believe me, I’m not a good communicator, send someone else.” She drops everything, does whatever it takes—because she feels it in her kishkes.

That was Moshe after that moment, as described by the Kotzker. He transformed from reluctant bystander to the greatest mover-and-shaker the Jewish people has ever known.

This is the hallmark of all our greatest leaders. Yosef HaTzaddik had it — he was emotional, concerned, loving, always looking after others. And he earned their trust, whether it was Potiphar, whether it was the people running the prison and fellow prisoners, whether it was Pharaoh and the entire Egyptian nation – and eventually it was his brothers as well.

King David had it too — he was an unlikely leader: a middle child, overlooked even by his own family, yet with a burning sense of duty to the Jewish people. The Gemara in Berachot tells us that he barely slept, he was so busy with his leadership duties during the day that he had to study Torah at night.

Because here’s the truth: you can’t be an effective servant of Hashem by just doing it on the outside, but not feeling it on the inside. Until it’s in your kishkes, you’ll never be effective. But once it is — once the fate of the Jewish people is part of who you are — there’s nothing you can’t accomplish.

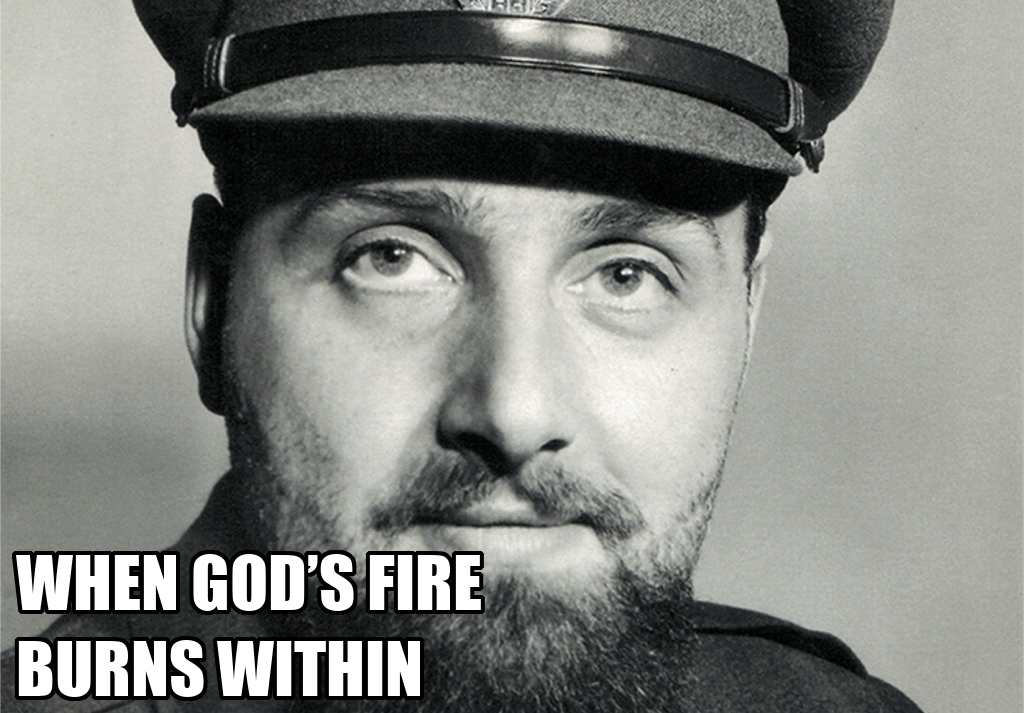

There’s one man in living memory who embodied this idea of וַיִּחַר אַף ה’ בְּמֹשֶׁה – an individual who had the burning passion of God inside him, and it resulted in him doing extraordinary things for the Jewish people. His name was Rabbi Dr. Solomon Schonfeld.

During World War II, when most of the British Jewish establishment was bogged down in cautious committee meetings and diplomatic delays, Rabbi Schonfeld — still only in his twenties — was burning with urgency to save Jews from Nazi Europe.

Rabbi Schonfeld was an unlikely choice to be a leader. When his father — the Chief Rabbi of the Union of Orthodox Hebrew Congregations in London — died in 1930, Solomon was only eighteen-years-old. And he wasn’t the oldest son. Besides, he hadn’t trained for the rabbinate. In fact, he had no formal plan for communal leadership at all.

The community was skeptical. But his mother was adamant. “I know him,” she told them. “He is a true leader. You’ll see.”

For a while, there was nothing dramatic — he went off to Europe to study – at Slabodka, at Nitra, at Konigsberg University. He came back to London and became the rabbi, quietly doing his job in the community.

But then came the late 1930s — Hitler’s Nazi Germany was suddenly persecuting and killing Jews – not only in Germany, but in Czechoslovakia and Austria. The clouds over European Jewry were getting darker and darker. And something happened to Solomon Schonfeld. וַיִּחַר אַף ה’ בְּמֹשֶׁה — The pain of European Jewry, the urgency of their plight, burned inside him.

Rabbi Schonfeld donned a self-created army uniform which mimicked a British military officer uniform, and he began doing extraordinary things. He didn’t have time for “process.” He forged papers. He bent immigration rules. He made personal financial guarantees to the British government for thousands of refugees — knowing that if he defaulted, he would be financially ruined.

In late 1938, at great personal risk, Rabbi Dr. Solomon Schonfeld crossed into Vienna, organized a Kindertransport of Orthodox children, and leveraged his authority — including personal guarantees — to bring them safely to England, even when doors were closing.

After the war, in 1946–47, he continued his rescue efforts by personally chartering a ship to bring orphaned child survivors from Poland to safety in Britain using inventive CRREC visas.

During the war, in one particularly unusual episode, Rabbi Solomon Schonfeld’s burning concern for the fate of his people drove him to attempt the impossible. In 1940, he raised £10,000 and purchased Strangers Cay, a remote island in the Bahamas, intending to use it as a refuge for Jews escaping Nazi Europe.

His logic was simple: if he owned the island, he could invite them freely, bypassing Britain’s immigration restrictions. The Colonial Office at first agreed, but another department later blocked the plan. It never happened — but the very fact that he bought an island for this purpose speaks volumes.

When asked later how he could take such huge risks, he said he could never live with himself knowing that he could have done something but didn’t. The suffering of the Jewish people was, for him, a constant, personal emergency.

This is the Kotzker’s “וַיִּחַר אַף ה’ בְּמֹשֶׁה” in modern dress. The pain and urgency of Hashem’s mission burned inside Schonfeld. There was no gap between the need and his response — no time for “I’m not the right person” or “send someone else.” Once it bunt inside him, he simply did it.

And that brings us back to the Shema. When the Torah says, וְחָרָה אַף ה’ בָכֶם, maybe it’s not only a warning of divine punishment. Maybe — as the Kotzker hinted with Moshe — it’s also an invitation. An invitation for God’s own burning urgency, His fierce love for Am Yisrael, to enter us.

If we let that fire in, it transforms who we are and what we can do — so that the bad things never happen, and the consequences of drifting away from God are never realized.

For Moshe, that moment turned a reluctant shepherd into the greatest leader in our history. For Rabbi Schonfeld, it turned a quiet young rabbi into a tireless savior of Jews. And for us — if we let it in — it can turn ordinary days into missions, ordinary choices into acts of leadership, and ordinary lives into legacies that matter.

Because once God’s burning passion is inside you… you can’t just stand by. You move. You act. You lead.