WILL IT WORK LIKE A CHARM?

If one is to believe the blurb, Heichal Hatorah Kollel in Manchester UK “is one of the foremost institutions of higher rabbinic scholarship in Europe.” Founded in 2002, the Kollel is headed by Rabbi Michoel Ber Weissmandl, a nephew of his namesake, the Holocaust whistleblower whose desperate and concerted attempts to alert the world to Nazi atrocities from behind enemy lines tragically fell on deaf ears.

Truthfully, I had never heard of Heichal Hatorah until just a couple of days ago, when someone forwarded me an email attachment – a “segulah” (mystical protective charm) text to hang on the inside of my front door, apparently distributed by the esteemed Kollel in the midst of this horrific coronavirus outbreak that has overwhelmed us all.

But whilst I appreciated the sentiment behind the gesture, I nonetheless felt the need to investigate this phenomenon further before printing out the attachment and putting it on my front door. After all, practical Kabbalah is not a simple matter, and although I fully understand the idea that “desperate times call for desperate measures”, I have an instinctive aversion to religious humbug and spiritual mumbo-jumbo, particularly if they prey on people’s fear and vulnerability in challenging times.

The only point of reference I had to work with as to the origins of this protective charm was a note at the top of the printout citing it as a literary product of the illustrious “Yismach Moshe”, Rabbi Moshe Teitelbaum (1759-1841) of Ujhely, today Sátoraljaújhely, Hungary.

Rabbi Teitelbaum is the forebear of one of the largest of all contemporary Hasidic sects – Satmar – although, in his day, his following was dwarfed by the far larger Hasidic groups of his colleagues. Nonetheless, he was widely respected and revered, and enjoyed a warm relationship – despite various disagreements – with the powerhouse rabbinic leader of his era, Rabbi Moshe Sofer of Pressburg (Bratislava).

The Jewish Encyclopedia – a comprehensive Jewish reference work published in 1906, now available as a free online resource – has a small article about Rabbi Teitelbaum, which inter-alia records the following anecdote: “In 1822, [Rabbi] Teitelbaum was suspected of having supplied amulets to certain Jewish culprits who had been cast into prison for libel, in order to assist them in escaping. When called upon to vindicate himself, he declared that the amulets in question served only as substitutes for the mezuzah, and that their only purpose was to protect their bearers against demons.”

Apparently, Rabbi Teitelbaum was very fond of composing and distributing amulets and charms, and not just for the benefit of Jewish felons. According to Rabbi Yekusiel Aryeh Kamelhar, an early twentieth-century pioneer of Orthodox Jewish historical scholarship, although Rabbi Teitelbaum, initially an opponent of Hasidism, was later a dedicated follower of the Hasidic mystic, the Seer of Lublin (1745-1815), in reality he was a throwback to a much earlier mystic, the fiery Kabbalist Rabbi Naphtali Katz (1649-1718), who, as a rabbi in Frankfurt, was arrested and imprisoned in 1711 after a fire ravaged that city’s Jewish neighborhood, accused of having relied “on the efficacy of his cabalistic charms [thereby preventing] the extinction of the fire by ordinary means.”

Numerous stories abound regarding the effectiveness of Rabbi Teitelbaum’s amulets and charms, and after his passing these holy texts were passed down generation to generation, used to ward off evil and to protect those vulnerable to sickness or other types of physical danger.

But unlike the obscure Kabbalistic jargon of amulets distributed by other eminent mystics, Rabbi Teitelbaum’s protective texts are by-and-large coherent and intelligible, containing well-known verses and familiar mantras, which allows one to read them and derive their meaning, even if one has zero training in Jewish mystical teachings.

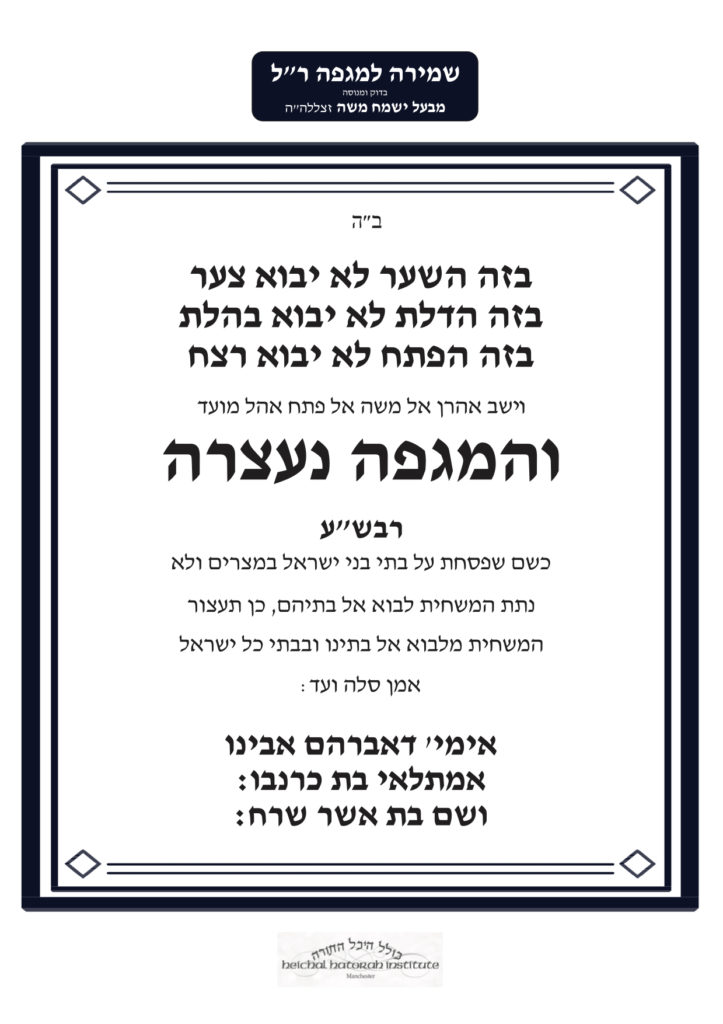

The Heichal Hatorah text is no exception to this rule, and moreover, it has irrefutable provenance as a Rabbi Teitelbaum protective charm composed specifically for use during a lethal epidemic.

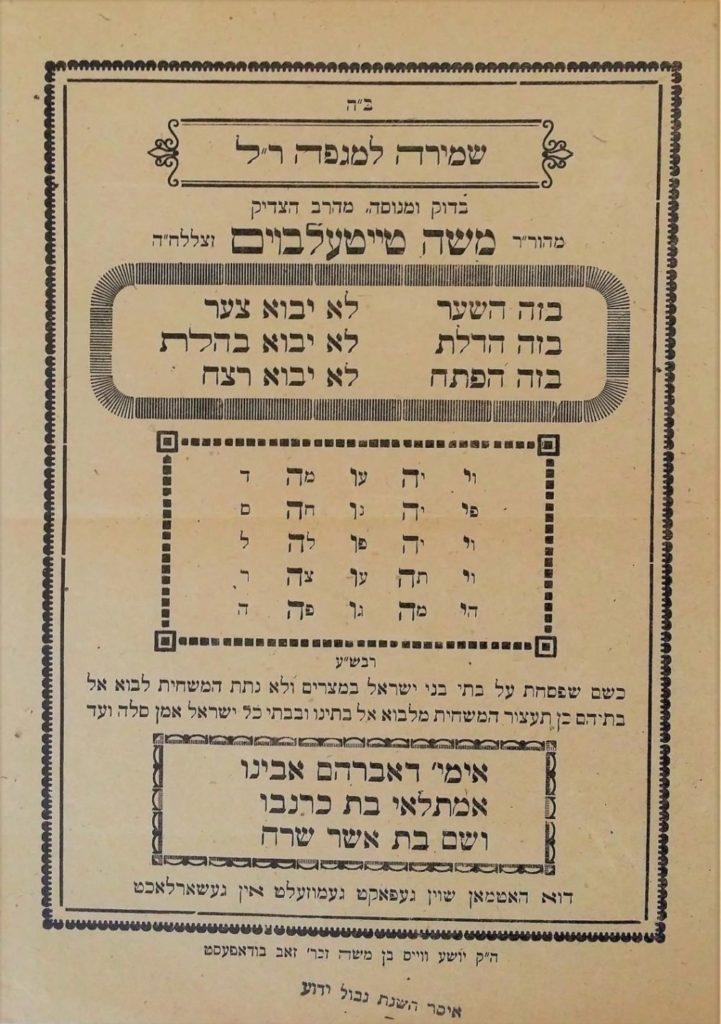

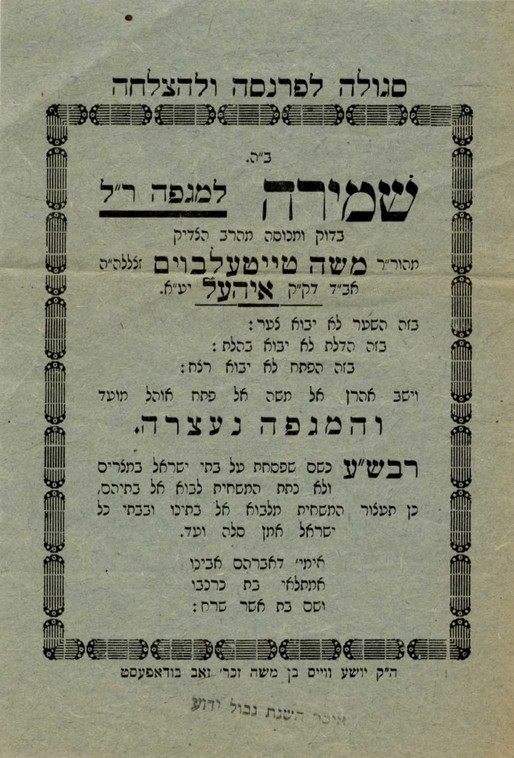

In December 2017, Rafaeli Auctions in Israel held an auction selling Judaica and Hebraica; Lot 159 was listed as an unknown, undated “leaf” for protection against “the plague”, composed by “the Admor Rabbi Moshe Teitelbaum, Yismach Moshe”, and printed in Budapest by the interwar Jewish printer, Joshua Weiss.

A similar handbill, also printed by Weiss, probably in the 1930s, was sold more recently (Lot 355), in January 2020, by TZolman’s Auctions. Both texts are identical to the text sent out by Heichal Hatorah, although the Rafaeli handbill has an additional Kabbalistic word arrangement inserted, involving the Tetragrammaton name of God (see images below).

The most remarkable aspect of the protective text I received from Heichal Hatorah is how unremarkable it is. I present here a full translation followed by some elucidation and explanation:

With God’s help

Into this gate, may no anguish enter;

Through this door, may no terror enter;

By this entrance, may no killing enter.

“Then Aharon returned to Moshe at the entrance to the Tent of Assembly, and the plague was ceased!”

Master of the Universe, just as You skipped over the houses of the Israelites in Egypt and did not allow the destroyer to enter their homes, so too may You prevent plague from entering our homes and the homes of all Yisrael, Amen, forever-and-ever.

Mother of our patriarch Abraham,

Amatlai daughter of Karnevo;

and Asher’s daughter whose name was Serach.”

The opening lines of this protective text are very familiar; they contain the earliest-attested text of what is known as Birkat Habayit, the general protective blessing formula for a Jewish home. This is hardly a Kabbalistic incantation, rather it is the kind of prayer one would and should readily utter every day in order to formally request God’s protection for one’s home and household.

The verse that follows (Num. 17:15), marks the end of the plague that struck the Israelites after they had accused Moshe and Aaron of murdering Korach and his followers, when Aaron used incense to achieve atonement, bringing an end to the divine punishment that had resulted in so many deaths. Once again, this seems entirely appropriate as a reference to the end of a deadly decree, and the fact that it will come about via an act of atonement.

The text then deviates into an improvised prayer for salvation from the raging “plague” currently ravaging one’s location, requesting that it skip over one’s home – just as God passed over Jewish homes in Egypt on the night of the Exodus, when every Egyptian home witnessed a death, while every Jewish home was spared (see: Ex. 12:27 and Ex. 12:23). Yet again, this reference falls well within the paradigm of normative prayer, invoking an event in biblical history as the springboard for divine mercy, illustrating how God saved His people in similar circumstances in the past, and asking Him to act similarly for us in the present.

The text does end on a more Kabbalistic note, invoking the names of two ancestors of the Jewish nation: Amatlai, daughter of Karnevo, mother of our patriarch Abraham; and Serach, daughter of Asher, the son of Jacob.

Abraham’s mother is not mentioned in the Torah, not by name, nor, indeed, at all. Nevertheless, she is identified by name by the second-generation Babylonian Talmudic sage, Rav Chanan bar Rava in the name of Rav (his father-in-law), in tractate Bava Batra (91a). Interestingly, Rav Chanan was very concerned that one might confuse Abraham’s mother with Haman’s mother: “Rav Chanan bar Rava says in the name of Rav: The mother of Abraham [was called] Amatlai bat Karnevo. The mother of Haman [was called] Amatlai bat Orevati. And your mnemonic, [to ensure that you don’t confuse them with each other, is that a raven (orev) is] impure, [which will help you remember that Orevati is the grandmother of the] impure [Haman, while a sheep (kar) is] pure, [which will remind you that Karnevo is the grandmother of the] pure [Abraham].”

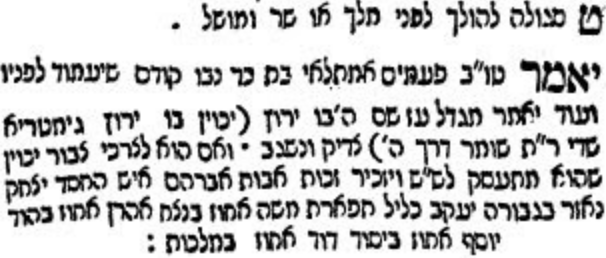

Rabbi Chaim Yosef David Azulai (Chid”a; 1724-1806) records (see illustration) that the name “Amatlai bat Karnevo” should be invoked for safety before approaching a figure of authority, which I assume must mean that the impending meeting could end with one’s unexpected violent death, God forbid. Rabbi Teitelbaum clearly took this one step further and added the name to his protective text as a means of protection from an unpleasant death via a fatal disease.

Finally, the protective text cites a verse in Bamidbar (Num. 26:46) that mentions Serach, daughter of Asher. The Midrash describes Serach in some detail, focusing on her virtuous character that resulted in her longevity. Her family seems to have known that her wonderful personality endeared her to Jacob, because she was the person chosen by Jacob’s sons to inform Jacob that his long-lost son Joseph had not actually died all those years earlier, but was still very much alive. Concerned that the shock of this revelation might result in Jacob’s death, Serach decided to hint the information to him while he was praying, composing rhyming lyrics that she innocently sang as he meditated before God.

Overwhelmed by her considerate act, Jacob blessed her with a long life, and indeed, it was Serach who informed Moshe where Joseph was buried on the night the Jews finally left Egypt so many years later, so that Moshe could disinter him for reburial in Eretz Yisrael.

It would appear, although I have no source to prove it, that Rabbi Teitelbaum’s invocation of Serach’s name is connected to her longevity, which was a gift based on her virtuousness – once again an allusion that falls well within the bounds of normative Judaism.

On the basis of all of the above, I see no reason why this protective text should not or cannot be used as a prompt to protect ourselves against an epidemic. Hanging the text on the inside of one’s front door will certainly give you useful cues for prayer, and for strengthening your confidence in God’s providence.

But even as we benefit from Rabbi Teitelbaum’s protective text, we should remember that his greatest feat was his incredible Torah scholarship and diligence in Torah study. Rabbi Yosef Shaul Nathansohn (1808-1875), chief rabbi of Lemberg (Lvov), in his laudatory introduction to Rabbi Teitelbaum’s posthumously published book of halachic responsa Heishiv Moshe (Lvov, 1866), records that in his youth the author “knew 800 pages of Talmud by-heart, with all the information methodically and perfectly organized.”

When a great and learned person such us Rabbi Teitelbaum of Ujhely invites us to use a particular set of texts as a way of elevating our chances of invoking God’s protection in difficult circumstances, I am more than pursuaded to take him seriously. May we all merit God’s protection at this very difficult time, and may we see redemption and salvation, very soon and in our days. Amen.

With thanks to Michael Bernstein and Shlomo Zuckier