WHY THE DEVIL WEARS PRADA

Most Hollywood movies are not particularly memorable, even the good ones, and it is rare for a feature film to make the kind of impact on popular culture that will outlast its run in the theaters and the next round of award ceremonies.

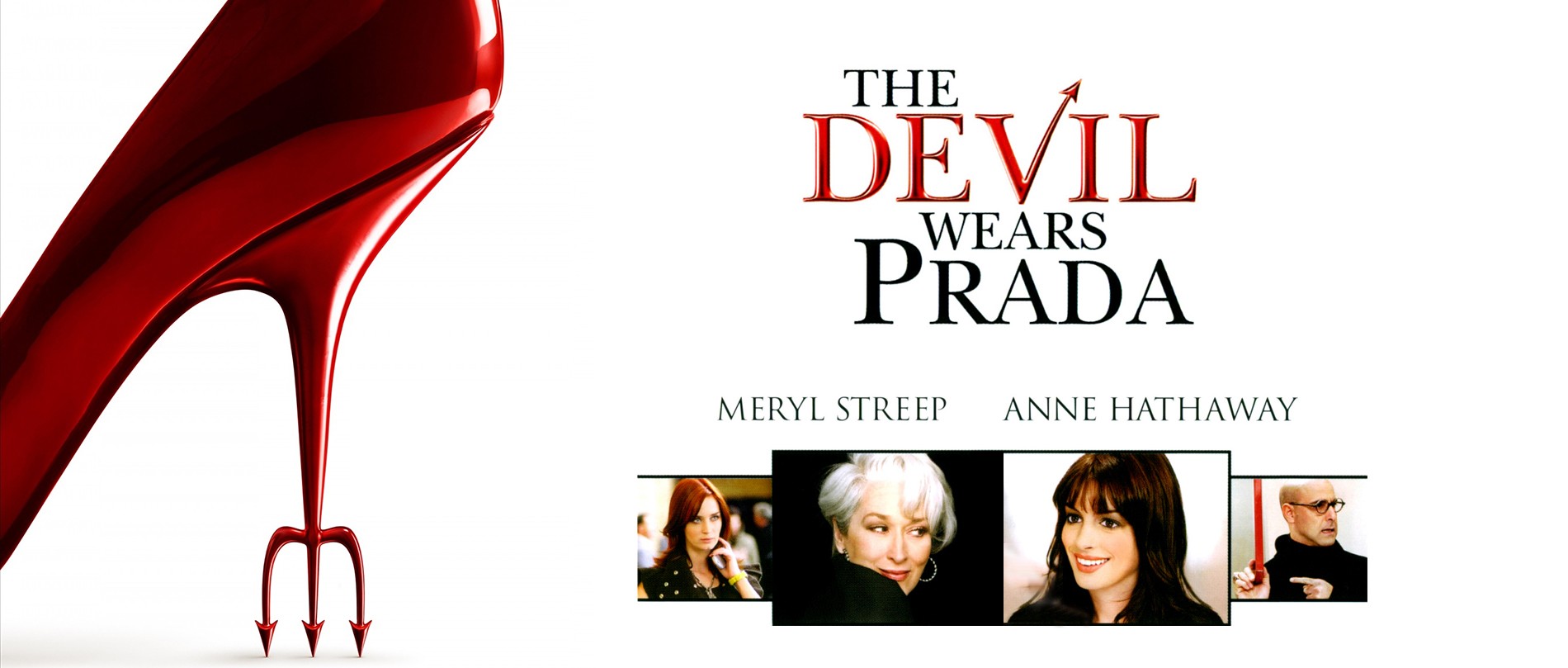

But one movie that has made a lasting impression, and continues to be considered one of the most iconic films of the last twenty years – and in the opinion of one quirky critic, the “best movie ever” – is the 2006 comedy-drama, The Devil Wears Prada, starring Meryl Streep and Anne Hathaway, which, according to reports this week, is about to be turned into a musical.

In the movie version, Hathaway plays Andy Sachs, an aspiring young journalist who sidesteps her contempt for the fashion industry to get a job as assistant to Miranda Priestly, editor-in-chief of a major fashion magazine, played by Streep.

The film focuses on the gulf that separates these two women, and particularly their very different attitudes towards the world of fashion.

The most memorable moment follows Sach’s involuntary disparaging chuckle as Priestly struggles to choose between two seemingly identical belts for a photoshoot – because they are “so different”.

In the short exchange that follows it becomes clear that Sachs cannot see the point in trying to detect the apparently meaningless differences between items of clothing or accessories, and why these things matter so much to those immersed in fashion.

Priestly gazes at Sachs contemptuously, noting her bright blue sweater. “OK, I see,” she says, “you think this has nothing to do with you. You go to your closet and you select that lumpy, loose sweater, for instance, because you’re trying to tell the world that you take yourself too seriously to care about what you put on your back. But what you don’t know is that that sweater is not just blue. It’s not turquoise. It’s not lapis. It’s actually cerulean.”

“And you’re also blithely unaware of the fact that in 2002, Oscar de la Renta did a collection of cerulean gowns, and then I think it was Yves Saint Laurent who showed cerulean military jackets, and then cerulean quickly shot up in the collections of eight different designers. And then it filtered down through department stores, and then trickled on down into some tragic Casual Corner where you no doubt fished it out of some clearance bin.”

“However, that blue represents millions of dollars and countless jobs, and it’s sort of comical how you think you made a choice that exempts you from the fashion industry when, in fact, you’re wearing a sweater that was selected for you by the people in this room from a pile of stuff.”

The idea behind this startling put-down – which has incidentally been hotly disputed by fashion industry insiders – is that there is a trickle-down effect in the clothing world that ordinary non-fashion obsessed individuals are utterly unaware of, but their ignorance does not change the fact that what appears on fashion runways, however ridiculous these displays may appear to the uninitiated, influences what ordinary people wear down the line.

Ultimately, we are all affected by things that go on far away from us, in arenas that are seemingly totally disconnected from our day-to-day lives.

Priestly’s monologue came to mind as I delved into a fascinating Kedushat Levi explanation of the Torah’s cryptic introduction to Rebecca in Chayei Sarah.

When we first encounter Rebecca, she is presented to us as follows (Gen. 24:15): וְהִנֵה רִבְקָה יֹצֵאת אֲשֶר יֻלְדָה לִבְּתוּאֵל בֶּן מִלְכָּה אֵשֶת נָחוֹר אֲחִי אַבְרָהָם – “And behold Rebecca emerged, who was born to Bethuel, son of Milcah, wife of Nahor, Abraham’s brother.”

Rather than telling us that Rebecca was Bethuel’s daughter, the Torah describes her as having been “born to Bethuel”, deliberately detaching her from her biological father, while the remainder of the verse expressly connects her to Abraham.

For the Kedushat Levi the explanation is simple. Everything boils down to cause and effect, even when we don’t relate an effect to the cause.

Rebecca was chosen by Eliezer to marry Isaac based on her superlative kindness towards him, an unknown stranger in need of assistance.

But where did Rebecca’s kindness come from? Her father was so nondescript that he barely registers in the narrative at all, while her brother Laban was evidently an unpleasant and unscrupulous villain. Rebecca certainly did not learn how to be kind from them.

But just as when fishing out a cerulean sweater from some clearance bin, we are unaware of the remote fashion industry world that resulted in that particular sweater being in that bin, the same is true in the spiritual realm.

When someone does a mitzvah, it has trickle-down energy that affects people and places well beyond that person’s immediate surroundings. The mitzvah brings a spiritual vibe into the world-at-large, and the knock-on effect results in numerous mitzvot by others, even people who have nothing to do with the person who did the mitzvah.

Moreover, if the source of the mitzvah is the equivalent of a top-rated fashion designer, namely an exemplar of that particular mitzvah, the effect of his mitzvah is magnified exponentially.

For example, as a result of one extraordinary person’s life-changing charity and generosity in New York, someone else will help a friend with carpool or collect their dry-cleaning in Los Angeles, and another person will volunteer to visit the sick in hospital in Jerusalem. The world will have become a different place, with “chessed” energy abundant and dynamic.

The Midrash says that as a result of Abraham’s extraordinary kindness, human kindness changed forever. Which means that although Rebecca may have been Bethuel’s biological daughter, her amazing kindness marked her out as Abraham’s spiritual heir, and therefore as a perfect wife for Isaac.

This crucial detail of who Rebecca was is underscored by the Torah’s introduction of her as having been born to Bethuel, but actually being more closely related to Abraham, whose kindness emanated through her in everything that she did.