WHEN IDEALISM ONLY EXISTS AS FANTASY

The Torah portion of Balak contains a story that is so strange, so bizarre, and so unusual, that the Talmud in tractate Bava Batra (14b) tells us that it is not included in the same textual category as the rest of the Torah.

In discussing who was responsible for writing down the five books of the Torah and the book of Joshua, the Talmud records that Moses wrote ‘his book’ and the ‘episode of Balaam’, while Joshua wrote ‘his book’ and ‘eight verses of the Torah’.

It turns out that the story of Balaam and Balak is a parallel narrative, given over to Moses as a prophecy outside the ordinary parameters of the Torah narrative, and it is therefore considered in its own category.

If we had to identify the most enigmatic character in the Torah, out of all the dozens, perhaps hundreds, of characters who crop up in the five books, we would almost certainly conclude – unanimously – that the number one unfathomable character is Balaam.

How does he make any sense? Who is this mysterious sorcerer called upon by some foreign king to curse a nation by whom he felt threatened? What is the deal with him and his talking donkey? Why does Balaam pretend to do Balak’s bidding, when he knows full well that he will not be able to curse the Jews?

The Torah itself tells us very little about his background. On the face of it Balaam seems like a man caught up in a story over which he has zero control. God tells him one thing; King Balak tells him something else. And then there’s the donkey with a third opinion!

There is no clue in the text of the story which reveals malicious intent by Balam. Quite the contrary – he seems to comply with God in every way, and simply humors Balak until it is all over.

The Talmud sees Balaam very differently and refers to him epithetically as Bilam Harasha – “Balaam the wicked”. In Tractates Berakhot and Sanhedrin, the Talmudic sages detail the hidden meaning behind every one of his statements, and explain how each of them indicates he was intent on helping Balak to exterminate of the Jews, and God thwarted him at every turn.

And yet his recorded words are vivid lyrics of poetic praise for the Jewish people. We utilize two of the statements he made in our prayers, but all of them are remarkable – carefully chosen words, describing an idyllic nation whose collective purpose is God and goodness.

So who is the real Balaam? Is he Balaam “the idiot”, caught in over his head? Or is he Balaam “the wicked”, determined to perpetrate a Holocaust? Or is he Balaam the “poet”, whose lofty words resonate through history?

Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehuda Berlin, known as the “Netziv” of Volozhin (1816-1893), the superlative Rabbi and Rosh Yeshiva of the nineteenth century who presided over the premier seat of learning in Europe for decades, puzzles over a particular verse in the Torah portion of Balak, found within the praises uttered by Balaam in his attempt to curse the Jews:

תָמֹת נַפְשִי מוֹת יְשָרִים וּתְהִי אַחֲרִיתִי כָמֹהוּ

“Let me die the death of the upright; let my end be like his.”

Balaam is speaking about the descendants of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob – the Jewish people. The Netziv is puzzled by the word ‘yesharim’. What does it actually mean? And why does Balaam want to be counted as one of the ‘yesharim’ and be remembered that way?

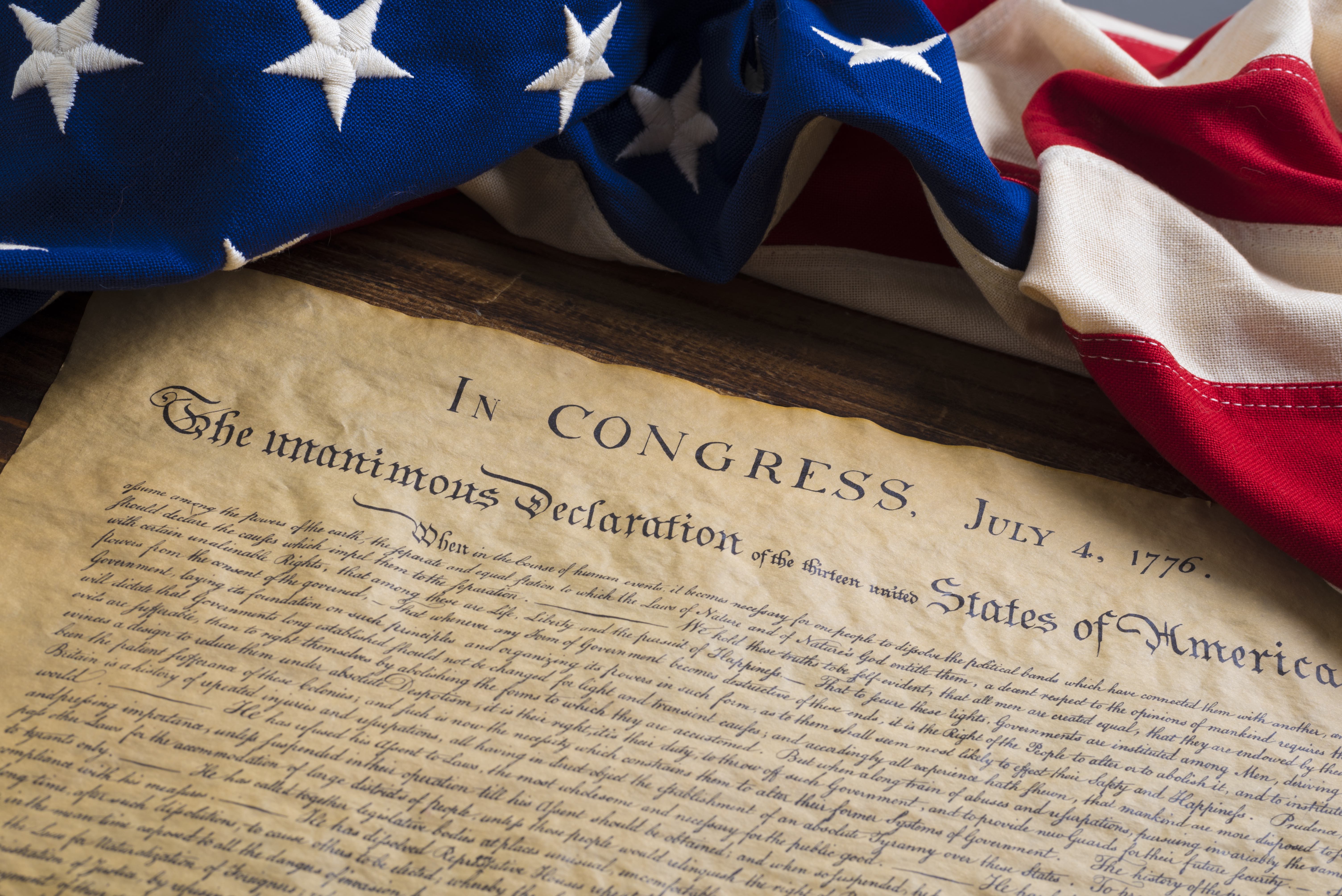

Before revealing what the Netziv has to say on this topic, let me just mention Thomas Jefferson, the quiet, cerebral farmer from Monticello, Virginia, who single-handedly composed the U.S. Declaration of Independence.

The declaration is an absolutely masterful document. Beautifully worded, crafted like an intricate sculpture, it conveys exactly what the revolutionaries intended by seceding from Britain and turning thirteen colonies into the United States of America.

In explaining the reasoning behind the secession, the declaration listed various grievances against Great Britain’s King George III, but more importantly Jefferson used this seminal document to set out the central ideal of the revolution – human rights and equality:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

That Jefferson would have begun the principle portion of his document with such a visionary statement is not just remarkable – it was the biggest upheaval of all.

The concept of a society based on equality, and on the recognition that each and every individual deserves freedom and happiness – not just well-born people, or rich people, or people of a particular religion, or color – was unheard of in 1776. That anyone who is a part of society, as long as he or she conforms to the laws of that society, can expect to be treated with respect and dignity, was utterly revolutionary.

“All men are created equal…they are endowed with certain unalienable Rights… among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

There is, however, a significant problem with Jefferson’s idealistic declaration – he was a slave owner. Some of the slaves were inherited; others he had bought. Some of the slaves he owned he later sold. Many of them were mortgaged as assets when he needed money.

None of this seems to be in the spirit of the ideas expressed in his idealistic declaration. How ‘equal’ were his slaves? What about their ‘liberty’, and their right to pursue ‘happiness’?

Apologists for Jefferson cite the fact that he lived in an age when universal slave emancipation was the fantasy of radicals, and it was perfectly normal to own slaves.

This is hardly a convincing defense. An idealist like Jefferson was surely not influenced by contemporary norms – he was, after all, an independent thinker actively breaking away from the rigid ideas of his times.

In any event, records show that other slave owners whose farms bordered his, freed their slaves – so why did he not do the same?

I think the answer is self-evident. Ideals are not facts. Ideals are ideals. We put them up on a pedestal, and then we revere them and we champion them. And often we do not quite match up to them.

Jefferson was the ultimate idealist. In many respects he reflected his ideals, but when it came to slavery – maybe he aspired to the ideal but was never able to make the break with the life he knew to be wrong.

The Netziv explains the word ‘yesharim’ so beautifully. He calls it an expression of the unconditional kindness that was the hallmark of the progenitors of the Jewish nation, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

Balaam knew about this inherited trait of kindness inherent in the Jewish nation. It was an ideal he aspired to, even though he knew that for him it was an impossible aspiration. Perhaps in old age he would finally succeed in conquering his mean-spiritedness and he would die as one of the ‘yesharim’ whose generous spiritedness he so admired.

Balaam knew what was right, he knew he didn’t match up to it, and he knew that the greatest thing that could happen to him would be for him to end his life having achieved this objective.