WHAT MAKES A TRUE LEADER?

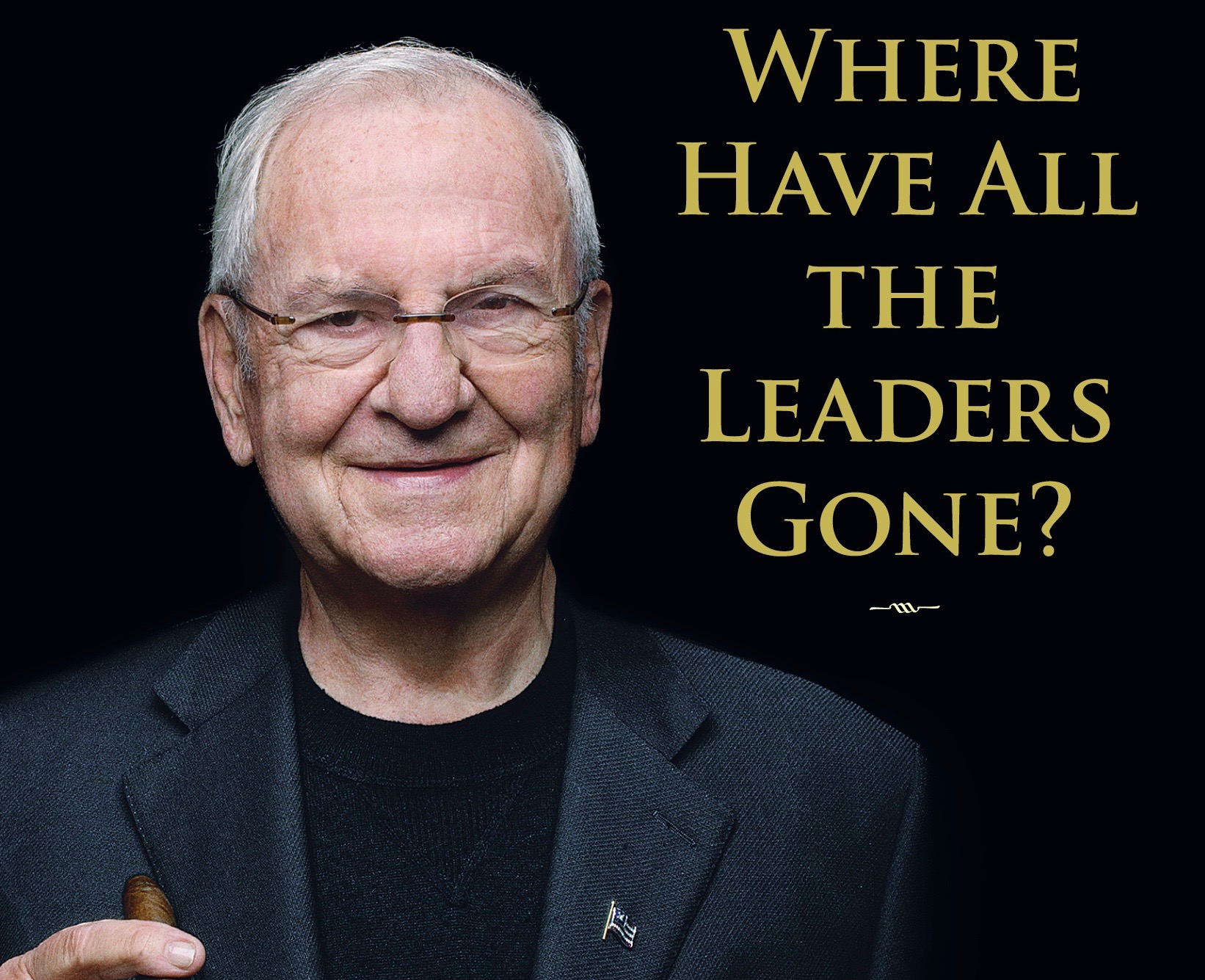

This week, motor-industry legend Lee Iacocca died at the age of 94.

Iacocca’s father, an Italian immigrant restaurateur from Pennsylvania, once told his son that “when you die, if you’ve got five real friends you’ve had a great life.”

But while that advice may have haunted Iacocca, the world is not going to judge him by how many friends he had, rather he will be evaluated on the basis of his groundbreaking successes as an inspired and inspirational business leader.

In his 2007 book, “Where Have All the Leaders Gone?”, Iacocca noted that leaders should be judged using “nine C’s of leadership”: Curiosity, Creativity, Communication, Character, Courage, Conviction, Charisma, Competence, and Common Sense.

“The job of a leader is to accomplish goals that advance the common good. Anyone can take up space, [but] the test of a leader [is simple] – when he leaves office, we should be better off than when he started.”

Any pointers from a man who revived the fortunes of not one, but two struggling motor giants – Ford and Chrysler – are worth considering seriously, but there is something missing from his list of C’s.

Rajeev Peshawaria, a leadership development lecturer used by some of the biggest names in

Remarkably, his audiences invariably complete the sentence using a variation of the same theme: “Leadership is the act of setting shared goals and inspiring/motivating people to work together towards achieving them.”

It turns out that most people believe that good leadership is defined by what a leader can get others to do, or by what they can do for others. But the history of great leaders tells a different story.

Mahatma Gandhi, the legendary Indian nationalist who led his country to independence and inspired civil rights movements across the world, had a different notion of his role as a leader, famously declaring “my life is my message”.

While Gandhi certainly possessed all of Iacocca’s C’s, the quality that really set him apart was his clear set of personal values, coupled with his relentless commitment towards achieving and upholding them. He never set out to lead others, only to lead himself, and consequently, those who followed him were not obeying orders, rather he was their role model of commitment to personal growth and the cause of Indian independence via non-violent means. Gandhi walked the walk, so his followers did the same.

The greatest leaders of Jewish history were all reluctant to lead, and their success as leaders was always a reflection of both their personal humility and their self-sacrifice.

King David’s introduction into scripture is via the recommendation of one of King Saul’s courtiers (1 Sam. 16:18), who tells the king that David is “a man of valor, a brave warrior, careful how he speaks, a man with presence, and God is with him.”

As the narrative unfolds, and Saul tries to kill him, David is always respectful and restrained, inspiring Saul’s own son Jonathan to recognize him as the true king. And yet, despite the acclaim, David resists the temptation to replace

Throughout the remainder of his life, King David demonstrated an extraordinary capacity for reflection and self-improvement, in spite of numerous setbacks and occasional failings, and is cited by the Talmud as the paradigm for repentance (Avodah Zarah 5a). Ultimately, notwithstanding his outstanding leadership qualities, King David’s elevated status in Jewish tradition is based on his personal journey, not on his charisma or communication skills.

Moses is similarly considered a model of Jewish leadership, not because he led the Jews out of Egypt, but as a result of his humility and selflessness.

Moses’ greatest nemesis was his cousin Korach, who challenged him to relinquish the leadership in favor of others equally suited to run the nation’s religious and civil affairs. After all, Korach argued (Num. 16:3), כִּי כָל הָעֵדָה כֻּלָם קְדֹשִים וּבְתוֹכָם ה – “the whole community is holy, all of them, and God is in their midst.”

Despite presiding over the most threatening challenge to Moses’ leadership, the Midrash portrays Korach as a wise and talented man. So what was it that led him astray?

The answer can be found in an exchange between Korach and Moses in the midst of the unrest. In an attempt to quell the rebellion, Moses challenged Korach to reveal his true intentions, and asked him whether he was demanding the priesthood.

The question appears redundant. Korach’s earlier statement that the entire nation was holy had surely revealed that the priesthood was exactly what he wanted. Why would Moses have asked Korach to confirm something he had already made clear?

Moses was making a rhetorical observation. To be a priest requires being holy, but not in the way Korach had portrayed it.

The Hebrew word

Aaron had never sought the role of High Priest; it had been thrust upon him, and he spent the remainder of his life trying to live up to the expectations of that role.

Similarly, Moses had been forced into his leadership

Moses was telling Korach that the very fact he had demanded a leadership position meant he was unsuited to it. While he was clearly charismatic and audacious, and no doubt checked every single one of Lee Iacocca’s leadership boxes, Korach lacked the crucial ingredient that propels someone from being a good leader to being considered an enduring example of leadership.

Korach’s selfish desire for power at any cost, even at the expense of integrity and personal growth, consigned him to the rogue’s gallery of biblical

Image: Motor-industry legend Lee Iacocca on the front cover illustration of his 2007 book, “Where Have All the Leaders Gone?”