WHAT CAN YOU SEE?

A good friend of mine sent me a YouTube link this week with an accompanying message: “You need a lot of time for this, but if you are into Holocaust history, this is one of the most incredible documentaries I’ve ever seen – and I’ve seen many!”

The documentary is Shtetl, produced and directed by Marian Marzynski – a Polish Jew spirited out of the Warsaw ghetto as a child, who then survived by being masqueraded as a Christian orphan and cared for by nuns.

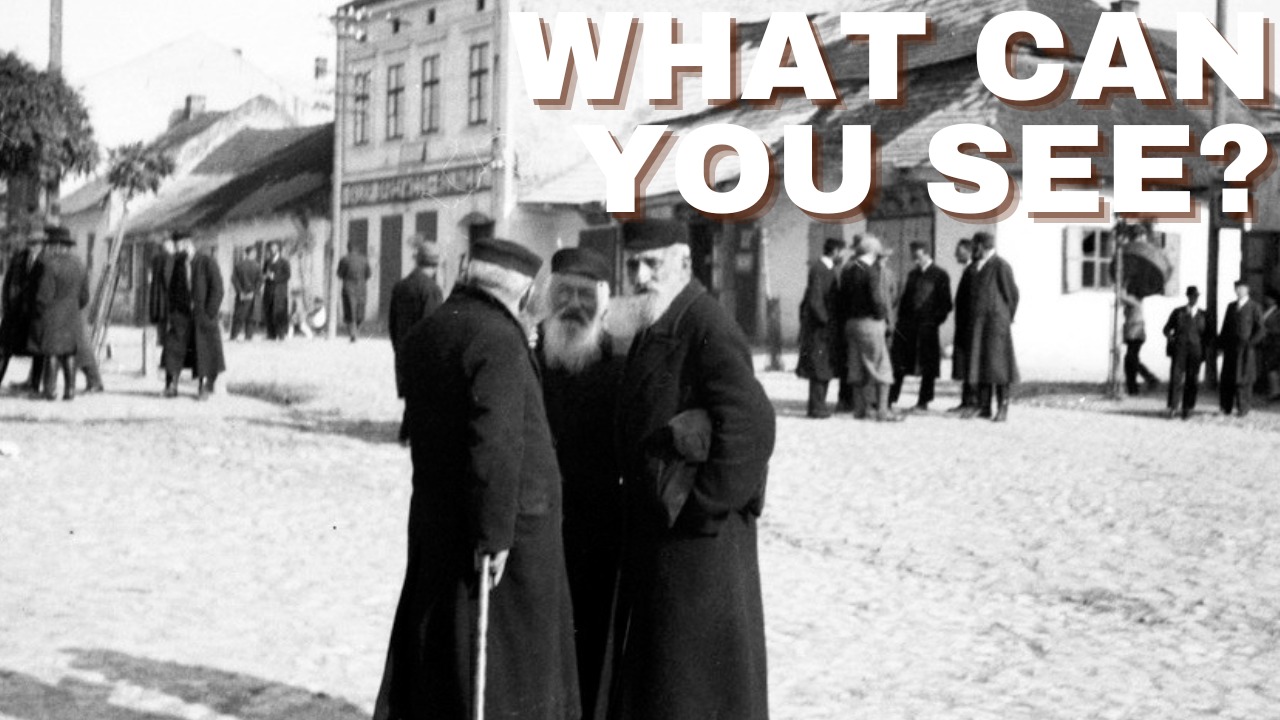

Shtetl, released by PBS in 1996, was originally envisaged as a documentary that would reveal the true nature of Jewish life in a minor Polish town, or “shtetl” – one that is now devoid of any Jews or Jewish character. For this purpose, Marzynski traveled to a backwater agricultural hamlet called Bransk (or Breinsk), about forty miles southwest of Bialystok in eastern Poland, near the border with Belarus.

For his first visit to Bransk, Marzynski was accompanied by a retired sales writer and gangster-history geek, American-born Nathan Kaplan, whose parents and grandparents came from Bransk. Their local contact, a mild-mannered 29-year-old gentile history buff, Zbyzsek Romaniuk, had been corresponding with Kaplan.

In response to Kaplan’s initial letter of inquiry, Romaniuk wrote: “There are no Jews in Bransk today, but I am a Pole whose family has lived here for generations, and I have an interest in Jews – I’d like to help you.”

Encouraged by this response, Kaplan quickly wrote back. “I am trying to recreate my family’s life in Bransk… I know my grandmother washed clothes in the river and walked on a cobblestone path to the mikvah. My mother was born in a one-room cabin. Would you know how those homes were furnished? Did people sleep on straw? Were there wolves in the forest? Were there bandits in the forest?”

“Dear Nathan,” came the reply, “your mother lived in very interesting times. Bransk had three marketplaces. Polish farmers from 60 villages sold corn, potatoes, eggs, horses, cattle, sheep, and poultry. In the market square, all the houses belonged to the Jews. In those houses, Jewish tailors, shoemakers, bakers, and sellers of fancy goods had their shops.”

Troublingly, Romaniuk has been targeted by local residents for his interest in the Jewish history of Bransk.

Before the onset of the Holocaust, Bransk not only had a thriving Jewish community, but Jews actually made up 60% of the town’s population. The community was mainly non-Hasidic, although there was a small Hasidic contingent.

In 1907, Rabbi Shimon Shkop (1860-1939) – later the famed spiritual leader of Lithuanian Jewry as the chief rabbi of Grodno – opened a yeshiva in Bransk together with Rabbi Ahron Shmuel Stein, whose son Rabbi Pesach Stein (1918-2002) was a postwar rosh yeshiva at the Telz yeshiva in Cleveland.

Although Bransk initially fell under Soviet control as a result of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, after the Nazi invasion of Russia in 1941 a Jewish ghetto was created, and in November 1942 all its inhabitants were dispatched to their deaths at Treblinka. In total, between 2,500 and 3,000 Bransk Jews were murdered by the Nazis.

And although Marzynski and Kaplan’s initial intent was to gather information about Jewish life in Bransk while it had still thrived before the Holocaust, very soon their inquiries took them in a totally different direction: a quest to find out which local residents were actively involved in the German effort to round up and kill Jews, and which residents assisted Jews in their attempt to survive.

Many of the Jew-betraying protagonists were still very much alive when the documentary was being filmed, and they spoke freely on camera – some of them defensively, many of them less so.

One old man tells Marzynski, “a Jew was worth as much as a rabbit is worth to a hunter; when a German saw a Jew, he shot at him like he would shoot at a rabbit – it gave him pleasure every time.” And the way he said it sounded like the pleasure was not just confined to the German.

Multiple survivor testimonies at Yad Vashem had mentioned the Hrycz brothers, who would offer Jews shelter, then grab their belongings, bludgeon them to death and throw their bodies into the river.

One of the brothers is still alive, and Marzynski visits him together with Kaplan. “I’ve heard a lot about you,” Marzynski tells him. Hrycz admits to having been arrested for killing Jews after the war, but claims it was someone else, not him, who committed the crimes.

And so it goes on, one old Pole after another: one a brazen looter, another one a blatant antisemite peddling antisemitic tropes as some kind of justification for what happened to their neighbors and “friends” – people who they did business and drank with, and in whose homes they lodged on market days, whose absence, and the vacuum their absence has left, the old Poles have a hard time even acknowledging.

Sometime later, a Bransk survivor – Jack Rubin of Baltimore, a.k.a. the “Goose King of Bransk” – returns to Bransk with Marzynski for the first time since the war ended. Rubin survived the Holocaust with the help of Bransk gentiles – whom he meets for the first time after a 50-year break and movingly acknowledges. But he also encounters raw antisemitism from a man who makes the ludicrous claim that Rubin’s father had cheated him out of 2 zlotys.

And throughout it all, Zbyzsek Romaniuk is a witness, trying to make sense of his local history in light of the countless revelations which indicate that his townspeople were at best passive accomplices, and at worst willing accessories, in the murder of Bransk’s Jewish population.

In one fascinating scene, Romaniuk engages with high-school kids in Israel after they have just returned from a Poland trip. It is absolutely clear that he – someone who is clearly not a Jew-hater – is unwilling or unable to acknowledge the egregious collaboration by so many Bransk residents in particular, and Poles in general, in the willful extermination of their Jewish neighbors, notwithstanding the compelling evidence he sees every step of the way.

Stunningly, in a letter to Marzynski after the documentary first aired, Romaniuk wrote: “this film is your vision of events, with which I cannot fully agree… It is too bad that the subject of Shtetl was mainly reduced to the Holocaust as executed by the Poles.” Remarkably, he adds: “Why does no one in the film ask the Jews if in a reversed situation they would help the Poles? I have asked such a question, and nobody said: ‘definitely yes’ – and some said: ‘probably not.’”

For me, Romaniuk’s blinkered vision is almost as disturbing as the Polish collaboration. Sometimes, you can observe something in front of your eyes, and you still don’t see it. The evidence is there, but your brain is in denial, finding rationalizations that blunt its edge or simply airbrush it away. No amount of demonstrable, empirical proof will make any difference.

Which is why every one of us needs to be on constant guard and conscious of this human failing – otherwise we can far too easily fall into the trap of denial as the go-to option, finding it so much easier than the pain which can accompany a vision of truth.

This explains the first word of Parshat Re’eh (Deut. 11:26): רְאֵה אָנֹכִי נֹתֵן לִפְנֵיכֶם הַיּוֹם בְּרָכָה וּקְלָלָה – “See, this day I set before you blessing and curse.” The word “re’eh” – “see” – seems superfluous. But it isn’t.

Moses needed the nation to know that their eyes can lie to them, and that unless they are willing to see – really see! – what is in front of them, what seems like a blessing might easily be a curse, which can result in the downfall of everything they consider important and precious.

Nothing has changed, least of all human nature. And Shtetl brought that reality into the sharpest focus.