VANQUISHING KHNUM THE RAM GOD

For as long as there have been historians and archaeologists, ancient Egypt has been an object of fascinated study and research. During the earliest era of human history, Egyptian influence and culture dominated the developed world, with its complex perception of the human experience and its sophisticated approach to every aspect of human existence.

And yet, unlike the cultures of subsequent world powers, such as those of the Greeks and the Romans, the impact of ancient Egypt on the world that ensued after its dramatic decline was minimal in real terms, with numerous features of its all-encompassing worldview abandoned entirely, in favor of new ideas that were precursors of many aspects of the world with which we are familiar in the twenty-first century.

The dominant view of historians is that it was an economic decline that precipitated the collapse of the Egyptian Empire. Egypt’s earliest pharaohs presided over a wealthy kingdom, and built temples, palaces, and pyramids. But Egypt’s prosperity was entirely contingent on the Nile River, which provided bountiful water to a country that is essentially a desert. All it needed was a few years of drought, amplified by military invasions and a range of bitter internal disputes, and the result was widespread ruin and irreversible decline.

But even if this explains why Egypt lost its status as a superpower, it does not explain why ancient Egypt’s approach to life and death, and to so many other aspects of the human condition, were completely discarded and replaced by the civilizations that followed on after it. From the sixth century B.C. onward Egypt was governed by a succession of foreign powers. But although these rulers left Egyptian culture largely intact, the ideas and ideals that this culture represented lost their grip, and eventually they vanished completely.

One possibility which might explain the ultimate complete collapse of Egyptian ideas and ideals is the determined approach of Judaism to replace the religion and culture of their former masters with a system that was the absolute antithesis of everything that Egypt represented. A remarkable example of this phenomenon is recorded as the very first instruction given to the nascent Jewish nation in anticipation of their impending redemption (Ex. 12:3): דַּבְּרוּ אֶל כָּל עֲדַת יִשְׂרָאֵל לֵאמֹר בֶּעָשֹׂר לַחֹדֶשׁ הַזֶּה וְיִקְחוּ לָהֶם אִישׁ שֶׂה לְבֵית אָבֹת שֶׂה לַבָּיִת – “Speak to the community of Israel and say that on the tenth of this month each of them shall take a lamb for their father’s house, one lamb per household.”

Rashi cites a Midrash which explains the reason for the Passover lamb and, in particular, why on this first occasion it had to be kept in their homes for four days before it was sacrificed. The ancient Hebrews, says Rashi, had lived in Egypt for centuries and they were completely steeped in idolatry. Consequently, the use of a lamb as a sacrifice to God and as the initiation rite of the Jewish people was no accident – it was a deliberate first step, intended to wean the descendants of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob off Egyptian paganism specifically because the sheep was a prominent Egyptian deity.

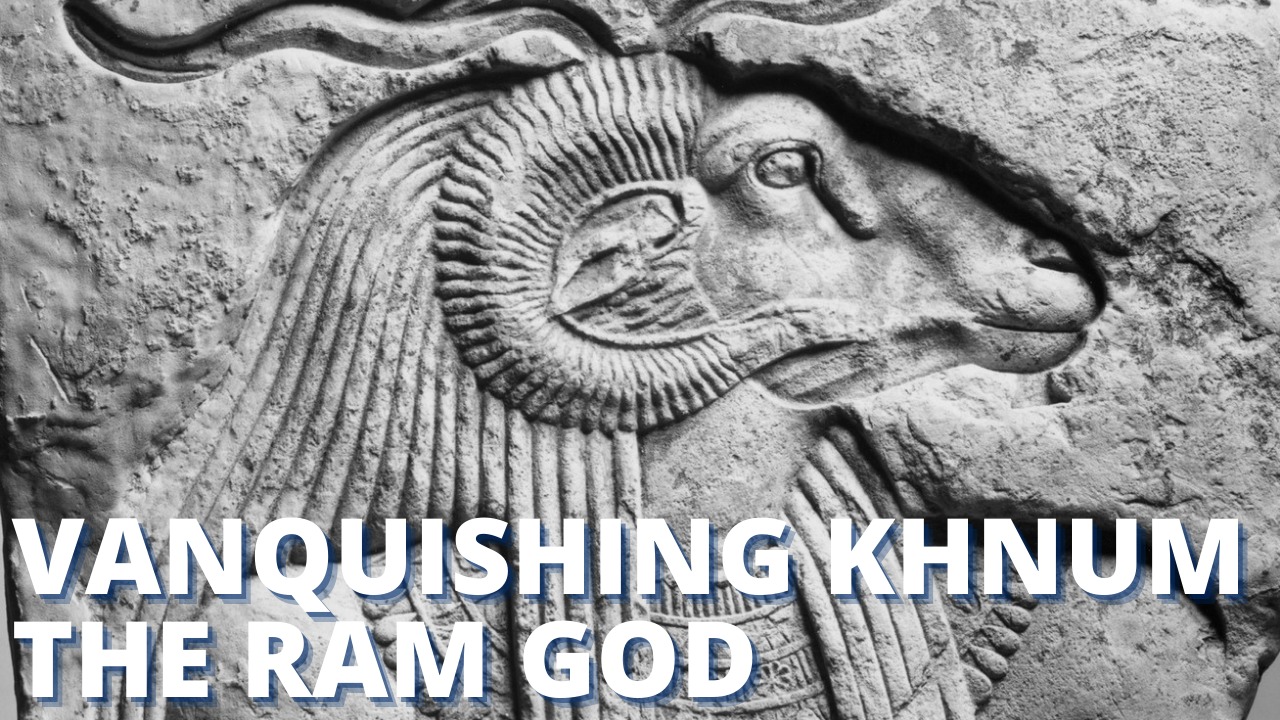

The deity in question was Khnum, usually depicted in hieroglyphics as a ram with horizontal twisting horns. Khnum was Egypt’s most dominant god before the rise of the sun god Ra, considered the god of fertility, also associated with water and the River Nile, and with procreation. Sometimes Khnum was represented as a man with a ram’s head, and it was also believed to have created the first human beings from clay, like a potter. It was for exactly this reason that Khnum – embodied by the young sheep – had to be slaughtered if the Jewish people were to emerge from Egypt the country, and Egypt the mindset.

And not only did the Jewish nation need to sacrifice this venerated symbol of Egyptian prosperity, but they were also instructed to set aside their sacrificial lamb four days before the designated date of sacrifice. At first glance, this four-day requirement seems somewhat superfluous. By the time the Jews were instructed to prepare the lamb for sacrifice and for its meat to be consumed at the first-ever Seder night, they had all observed in very close proximity as their Egyptian enslavers had endured nine devastating plagues wrought by God as part of the countdown to salvation. Surely they no longer needed to be weaned off idolatry – God had made Himself amply known via these miracles and wonders. So why the need to vanquish Khnum by preparing the lamb four days in advance?

According to Rabbi Henoch Leibowitz (1918-2008), the specific requirement to prepare the lamb four days before the fourteenth of Nissan was a consequence of the human weakness for bad habits. Of course the Jews believed in God, but they had nonetheless got into the bad habit of idol worship even as they declared their fealty to God. And when something is so deeply ingrained in a person, it is almost impossible to remove it.

Despite the evidence of God in front of their eyes, the idea that Khnum was not real or that Khnum could be sacrificed to God was not something the Jews could simply take on board from one moment to the next. Their belief in idols lingered on, and it needed to be worn down over a period of time. It was for this reason that the lamb was taken into their homes a few days before.

Even today, thousands of years after the Egyptian empire has disappeared and is no longer a material or spiritual threat to the Jewish faith, we are still instructed to spend time preparing for Passover, the festival designated as a time to commemorate our rescue from the dangers posed by this anti-God culture.

None of us are safe from bad habits, even if we believe in God. Aspects of our lives fly in the face of God-belief. Passover, but in particular the days leading up to Passover, when we get ourselves ready for this annual celebration of our most seminal moment, acts as a reminder that all of us need to be weaned off any bad habit that distracts us from our primary directive: a close and meaningful relationship with God.

We all have a Khnum hovering somewhere in the background. Passover offers us the opportunity to embrace the alternative to Khnum’s destructive force, so that we can all experience our own personal redemption.