UPSIDE DOWN, BACK TO FRONT

A couple of weeks ago, during our Torah reading on Shabbat, the Torah reader suddenly stopped in his tracks and bent down towards the parchment of the scroll to take a closer look at one of the words he had just read. He noticed that there was ink missing in one of the letters and was wondering whether this invalidated the Torah scroll, which meant it would need to be replaced with another scroll for the reading to continue. He called me over to the bimah, and I peered at the word with total focus – glasses on, glasses off, glasses back on again. “No, it’s fine,” I told him. “The outer rim of the letter is still intact, and the letter is therefore considered whole. You can continue using this Sefer Torah.”

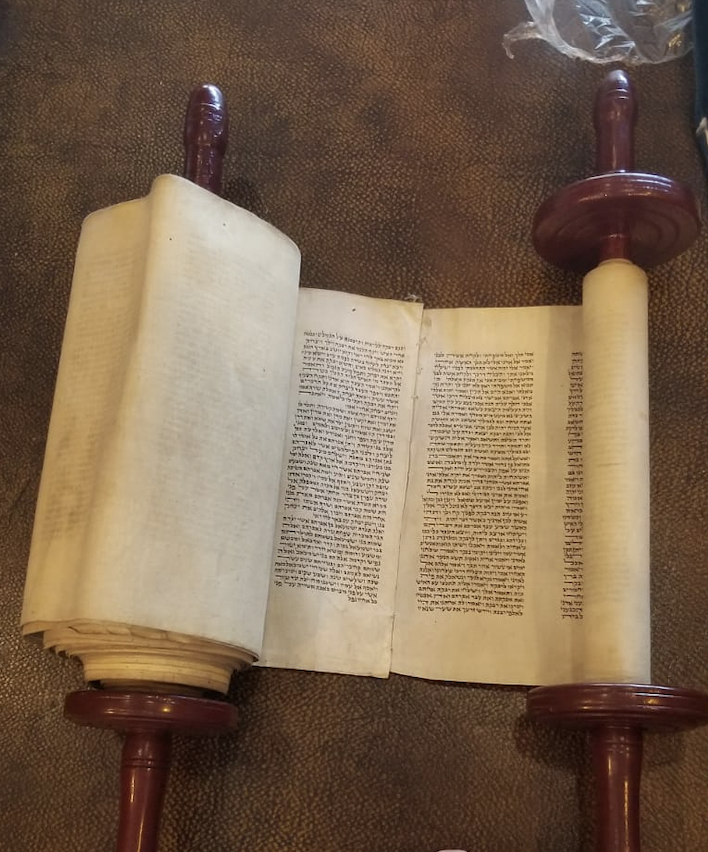

We all breathed a sigh of relief, but I made a mental note to call a sofer (ritual scribe) after Shabbat, to make sure that the letter was re-inked. As it turned out there were a couple of other letters in that column that had also faded, and we needed to re-ink them too. I’ve decided to have this scroll – which has been in my family for almost a century and was rescued from the Holocaust – fully checked using the state-of-the-art computer program which has totally revolutionized this process.

But the incident reminded me of a story I heard about a year ago – a story that astounded me, and serendipitously, it is a story connected to Parshat Behaalotecha. My late father had a close friend, a Holocaust survivor from Vienna. As a young man my father’s friend witnessed Nazis desecrating Jewish holy objects as part of their campaign of persecution against the Jews of Vienna after the 1938 Anschluss. What disturbed him most of all was the sight of Torah scrolls unfurled on the street, with Jews forced to walk on their sacred scripture while Nazi onlookers laughed and shouted abuse. Then and there he made a vow that if he ever became a man of means, he would underwrite the writing of new Torah scrolls and donate them to synagogues and yeshivas.

He survived the Holocaust years, and with a combination of hard work and God’s blessings he became an extremely successful businessman, renowned for his philanthropy as well as for his piety and devotion. Characteristically, he never forgot the vow he had made on the streets of Vienna in 1938, and over time sponsored nineteen Torah scrolls, the majority of which he donated to various institutions and synagogues around the world, although there were a couple he kept at his home.

Nineteen years ago, on Yom Kippur afternoon, while reading from one of the donated Torah scrolls during mincha, the reader suddenly noticed a cracked letter. It was a scenario not dissimilar to the one that played out at our synagogue: the rabbi went over and examined the damaged letter that had been spotted by the reader. But unlike our situation, the rabbi confirmed the worst – the letter was no good, and the Torah scroll was not fit to use for public readings. But that wasn’t the end of the story. The rabbi knew that their synagogue’s Torah was not the only one my father’s friend had commissioned and donated. He approached the family and suggested that all the donated scrolls be checked immediately.

But my father’s friend – already well in his seventies – would not hear of it. “Absolutely not, no way!” he told his family, “every single one of those Sifrei Torah was checked by four different soferim – there’s nothing wrong with them.” “But a mistake was found,” the family insisted. He shook his head. “No. They were written by the best; they were checked by the best – and they are the best. There’s absolutely no reason for any of them to be checked.” He was adamant.

Despite his firm stance, the family decided to go ahead and get them all checked anyway – although, as a mark of respect to their father, they decided to do everything to ensure that he wouldn’t find out. This strategy presented no problem for the Torahs at synagogues and institutions, but the ones at his home were rather more problematic. After much deliberation, the family decided to carefully remove the scrolls for checking while their father was out, and then to sneak them back without him ever realizing they were gone.

Remarkably, besides for the one cracked letter discovered in that one Torah on Yom Kippur afternoon, every one of the Torah scrolls they checked was totally perfect – not one cracked letter and no missing letters or words. All of the Torahs, that is, besides for one. And there was a problem – it was one of those he kept at home. The even weirder part was that the mistake they found wasn’t a mistake anyone had ever seen before.

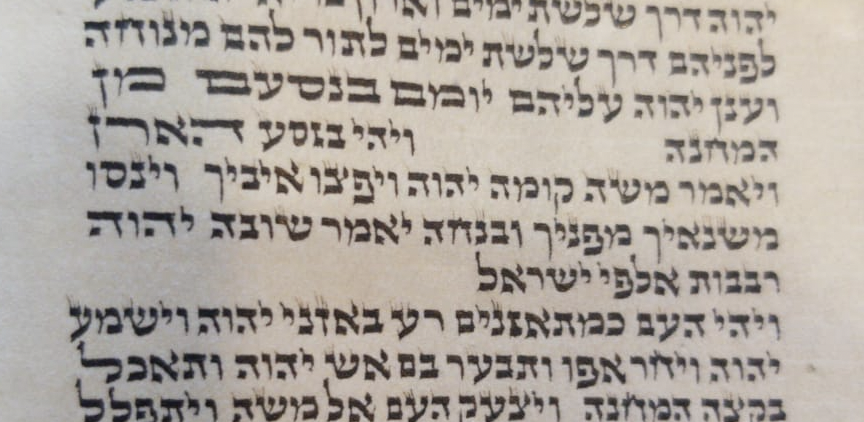

The Talmud in Shabbat (115b-116a) states that there are actually seven books in the Torah, not five. For reasons I won’t delve into here, this startling idea is based on the fact that there are two verses in Parshat Behaalotecha which are separated from the rest of the Book of Numbers by a pair of reversed, upside-down “nun” letters, which turns what is one book into three. The two verses are very familiar to us, as we recite them when we take and return Torah scrolls from and to the ark (Num. 10:35-36): וַיְהִי בִּנְסֹעַ הָאָרֹן וַיֹּאמֶר מֹשֶׁה קוּמָה ה’ וְיָפֻצוּ אֹיְבֶיךָ וְיָנֻסוּ מְשַׂנְאֶיךָ מִפָּנֶיךָ וּבְנֻחֹה יֹאמַר שׁוּבָה ה’ רִבְבוֹת אַלְפֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל – “When the Ark [of the Covenant] began to journey, Moses would say: “Advance, God, may your enemies be scattered, and may Your foes flee before you!” And when it rested, he would say: “Return, God, you who are Israel’s myriads of thousands!”

The two upside-down “nun” letters are an arresting sight, stuck in the middle of blank spaces before and after the text of these two verses. But astonishingly, in the Torah in which the mistakes were found, these two upside-down “nun” letters were missing, and instead, there were two upside-down “nun” letters in the text itself – one at the beginning of the first of the two verses, and the second in the first verse of Chapter 11. The sofer who checked the Torah was very clear: while there had been a custom to write the “nun” letters this way centuries ago, there was no way any contemporary scribe engaged to write a Torah scroll would write them this way, and if they did, the Torah was automatically invalidated and could not be used.

The family were in a quandary. What were they to do? How could they inform their father that they had disobeyed him and had the Torah checked? But silence was not an option – this was a Torah that he used, and the sofer was unequivocal: it was not fit for use! After some discussion, the family decided to gently tell their father what they had done, and to explain that the original cracked letter had convinced them that despite all of his precautions when originally requisitioning the Torahs, it was still possible for ink to peel away over time, and they wanted to be totally sure all of them were in good condition. And now – they had found this glaring error! Nervously, they met with their father to tell him what had been discovered.

He listened to them patiently. Then he smiled. “Let me tell you the story of this Sefer Torah,” he said. He sat back in his chair, with a faraway look in his eyes. “I can’t remember exactly when, but it was during the 1950s – the Jewish museum in London had an exhibition of European Jewish artifacts. I visited the exhibition and was shocked to see that there was a Torah open in one of the display cases – it was unrolled, a few columns were visible through the glass, totally against the halacha. My experience in Vienna, seeing Sifrei Torah desecrated on the streets – I just couldn’t allow a Torah scroll to be desecrated in front of my eyes again, and in a Jewish museum of all places!”

“I approached the curator and asked him to close the Sefer Torah. He refused, telling me I couldn’t tell him how to run his museum. So I said to him: I’ll buy it – that will solve the problem. He laughed. You couldn’t afford it, he said. Try me, I replied. He gave me a number, it was very high – much higher than the market value of the Torah. But without pausing for even a second, I took out my checkbook and paid for it. The staff at the museum removed the Torah from the display case and gave it to me, and I took it home. It’s an early eighteenth-century Torah, I had it restored and then checked by the best soferim, and they all assured me that it is 100% kosher. So you’re worried about the upside-down “nun” letters? Talk to the experts – they will explain it to you.” And the discussion was over.

And as it turned out, my father’s friend was right. In a detailed response to a query posed by Rabbi Pinchas Katzenellenbogen of Boskowitz (1691-1765?), the heavyweight halakhist Rabbi Yechezkel Landau of Prague (1713-1793) took an earlier rabbinic giant – Rabbi Shlomo Luria of Lublin (“Maharshal”; 1510-1573) – to task for suggesting that the correct way to separate the two verses from the Book of Numbers was to insert upside-down “nun” letters in the text itself, rather than in spaces before and after, on the basis of his interpretation of the relevant Talmudic passage and his view that adding “extra” letters to a Torah scroll would render the scroll unusable.

Rabbi Landau – best known by the title of his halakic work Noda BiYehuda – offered a respectful but erudite refutation of Maharshal’s view, but then proposed a stunning concession, clearly on the basis that there were many existing Torah scrolls in the mid-eighteenth century which would have become unusable if his ruling was followed unconditionally. “From today onwards,” Rabbi Landau said, “if a sofer is engaged to write a Sefer Torah, they should do it in this way.” From now on, he was saying, it would have to be upside-down “nun” letters in spaces before and after the verses, not in the text – if you wanted your Sefer Torah to be kosher. Which meant that those Torah scrolls written in earlier times following Maharshal’s opinion remained valid to use until age, wear and tear would confine them to genizah. Once these older scrolls were all in genizah, every remaining Torah scroll in circulation would follow the Noda BiYehuda’s opinion and the problem would be resolved.

But I’m guessing that the Noda BiYehuda hadn’t reckoned with my father’s friend, whose rescue and spare-no-expense restoration of the early eighteenth-century Torah meant that Rabbi Landau’s exception allowing a Maharshal Torah to be considered kosher could still be applied to at least one Sefer Torah – well into the twenty-first century!

My father’s friend died a few years ago, but the Maharshal Torah scroll remains very much in use. The family sent me photos of the “nun” anomaly in this kosher-to-use Torah – and I consider it a unique example of the rich range and variety within the halakhic system, a system that has kept us going as Jews for millennia, and which continues to sustain us and guide us in every aspect of our lives.

For further research, see: Shu”t Noda Biyehuda, Vol. 1, Y.D. #74; Shu”t Maharshal, #73; Kasher, Rabbi Menachem M., Humash Torah Sheleima, Vol. 29, Ketav HaTorah Ve’otyoteha, Chap. 11, pp.124-132 & pp.162-168. Thank you to Menachem Butler for providing me with a number of articles regarding this curious phenomenon.