TRAILBLAZER OF RELIGIOUS ZIONISM

It was a regular Shabbat afternoon in the early spring of 1891, and 21-year-old Moshe Reines – son of Rabbi Yitzchak Yaakov Reines – reached for the top shelf of the bookshelf in his father’s study to remove a book. Suddenly, without warning, the entire bookcase collapsed on top of him, crushing him with its weight.

The Reines family desperately tried to save his life, but to no avail; Moshe – a prodigy who had mastered the entire Talmud and was an acknowledged expert in Jewish history – was dead. Despite the shocking tragedy, his father remained totally calm, even as it became clear that Moshe’s life had been snuffed out. Without expressing any emotion, Rabbi Reines told the family to leave Moshe’s corpse in the study until after Shabbat. They all traipsed out, and Rabbi Reines closed the door and went off to synagogue for prayers.

After maariv, Rabbi Reines returned home and made havdalla for his family. Even as he recited the havdalla blessings, he was still a picture of tranquility. But moments later, once havdalla was done, Rabbi Reines turned pale, his eyes rolled back, and he fainted to the floor. Shabbat had formally ended, and he no longer needed to stay serene so as not to interfere with the Shabbat atmosphere. With the pressure off, Rabbi Reines did what any father would do when their son dies in a tragic accident – he collapsed to the ground in a heap of unbearable grief.

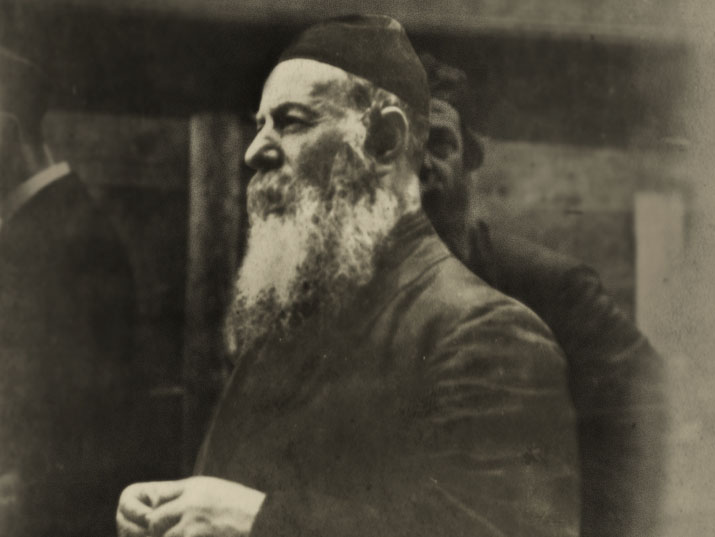

Rabbi Reines’s two-stage reaction to his son’s death made such an impression on his family, that it is still recalled with awe by his descendants. In January 2020, at an event inaugurating the gift of Rabbi Reines’s archives – a collection of 20,000 handwritten manuscript pages – to the Hebrew National Library in Jerusalem, it was the central story of a speech given by his great-granddaughter. And indeed, it is this story that encapsulates Rabbi Reines, who balanced his utter devotedness to God with a deep-seated humanity, and whose superhuman religious faith was the hallmark of his exceptional personality.

Rabbi Reines came from a background steeped in difficulty and tragedy, and at the same time enveloped in hope and optimism. His father, Rabbi Shlomo Naftali Reines (1797-1889), was part of a group – followers of the Vilna Gaon – who moved from Lithuania to Eretz Yisrael in 1809. The members of this group, led by Rabbi Yisrael of Shklov (1770-1839), were motivated by a mystical conviction that mandated living in the Holy Land in anticipation of messianic redemption. They settled in Tzfat, where living conditions were rudimentary, and supporting a family was almost impossible.

Rabbi Shlomo Naftali was an energetic, enterprising man, and he opened a printing press for Hebrew books. For a time, his publishing business was quite successful. But in 1834, local Arabs revolted against the Egyptian governor of Palestine, Ibrahim Pasha, and as part of the rebellion initiated a vicious pogrom against the Jews of Tzfat. During the riots, Rabbi Shlomo Naftali’s printing press was destroyed, and he was left destitute. Then, at the request of communal leaders, he traveled to Russia and Poland to raise money for the Tzfat community. But while he was in Warsaw Rabbi Shlomo Naftali heard the terrible news that his entire family – his wife and seven children – had been killed in an earthquake that devastated Tzfat on January 1, 1837.

As a result of this disaster, in which 1,800 people were killed, the Jewish community of Tzfat dramatically declined. On the advice of friends, Rabbi Shlomo Naftali remained in Europe and settled in the city of Pinsk-Karlin. The following year he remarried, and in 1839 had a son, whom he named Yitzchak Yaakov. This boy would go on to be an outstanding educator and leader, paving the way for Orthodoxy in modernity, both in terms of education and in terms of Jewish national aspirations.

Rabbi Yitzchak Yaakov Reines studied in the yeshivas of Volozhin and Eishishok, where he excelled as a Talmudic scholar. At the age of 19 he married the daughter of Rabbi Yosef Reizin (d.1885), a celebrated rabbinic leader – the rabbi of Telz and later Slonim. In 1867, at the age of 28, Rabbi Reines was appointed to the rabbinate of Saukenai (Shukian) in Lithuania, and in 1869 he became the rabbi of Svencionys (Shvintzian). There he began to write and publicize a highly original approach to the study of traditional Jewish texts, a curriculum which included general-knowledge topics extrapolated from Talmudic material and other rabbinic sources. But although many of his colleagues welcomed this original approach, there were those who opposed it on the grounds that it crossed the self-imposed red lines of traditional Orthodoxy.

Undeterred, in 1884 Rabbi Reines opened a yeshiva based on his innovative system. He called the yeshiva Torah Ve-Daat (“Torah and Knowledge”), and introduced a groundbreaking integrated curriculum which included Tanach, Talmud, halacha and general studies – all aimed at training rabbis who would be firmly rooted in tradition while also able to operate in the rapidly assimilating Russian-Jewish community. But vigorous opposition forced the yeshiva’s closure after four years, and it wasn’t until 1905 that Rabbi Reines was able to reopen his yeshiva, this time in Lida.

It was in Lida that Rabbi Reines first promoted the idea of embracing political Zionism, a movement led by secular Jewish nationalists actively working towards the creation of a sovereign Jewish state for the first time in almost 2,000 years. Rabbi Reines had previously been involved with the Hovevei Zion movement, which promoted Jewish settlement in Palestine. But with the advent of Zionism in the mid-1890s, many rabbis who had eagerly supported Hovevei Zion became horrified by the prospect of an irreligious Jewish state, and openly criticized Zionism and its secular leadership.

Initially, Rabbi Reines remained neutral, and he did not attend the first two Zionist congresses of 1897 and 1898. But in 1899, Rabbi Reines decided that the issue of Jewish hegemony over Eretz Yisrael was too important to be set aside for any other considerations, and he attended the Third Zionist Congress in Basel. Overwhelmed by the experience, he became a devoted and determined proponent of the Zionist cause.

He later wrote, that after returning home, a group of his anti-Zionist colleagues came to see him to persuade him to leave the Zionist movement. But Rabbi Reines firmly believed that Zionism was the only way forward for Torah-observant Jews, and he was determined to lead an Orthodox group within the Zionist movement that would become a beacon of Religious Zionism. Even the Chofetz Chaim – one of his closest friends – was unable to change his mind, and in 1901 Rabbi Reines formally launched the Mizrachi movement. With Rabbi Reines at the helm, Mizrachi immediately became the exclusive organizational home for Religious Zionists, and one of the strongest membership groups within the Zionist movement as a whole.

Rabbi Reines passed away in 1915 at the age of 76, but his legacy is broad and deep. Orthodox Judaism was only able to participate in the Zionist project as a result of his deep commitment to political Zionism, and it was his visionary leadership which ensured that at every stage leading up to and then after the creation of the State of Israel, as a direct result of the Mizrachi movement he created, Israel would be a “Jewish” state rather than just a state for Jews.

This article appeared in HaMizrachi Chanukah Edition 5782 (Volume 4, Number 7)