THE TRIUMPHANT MESSAGE OF NAOMI IN THE BOOK OF RUTH

For many Holocaust survivors, Shavuot was their first festival after liberation from concentration camp.

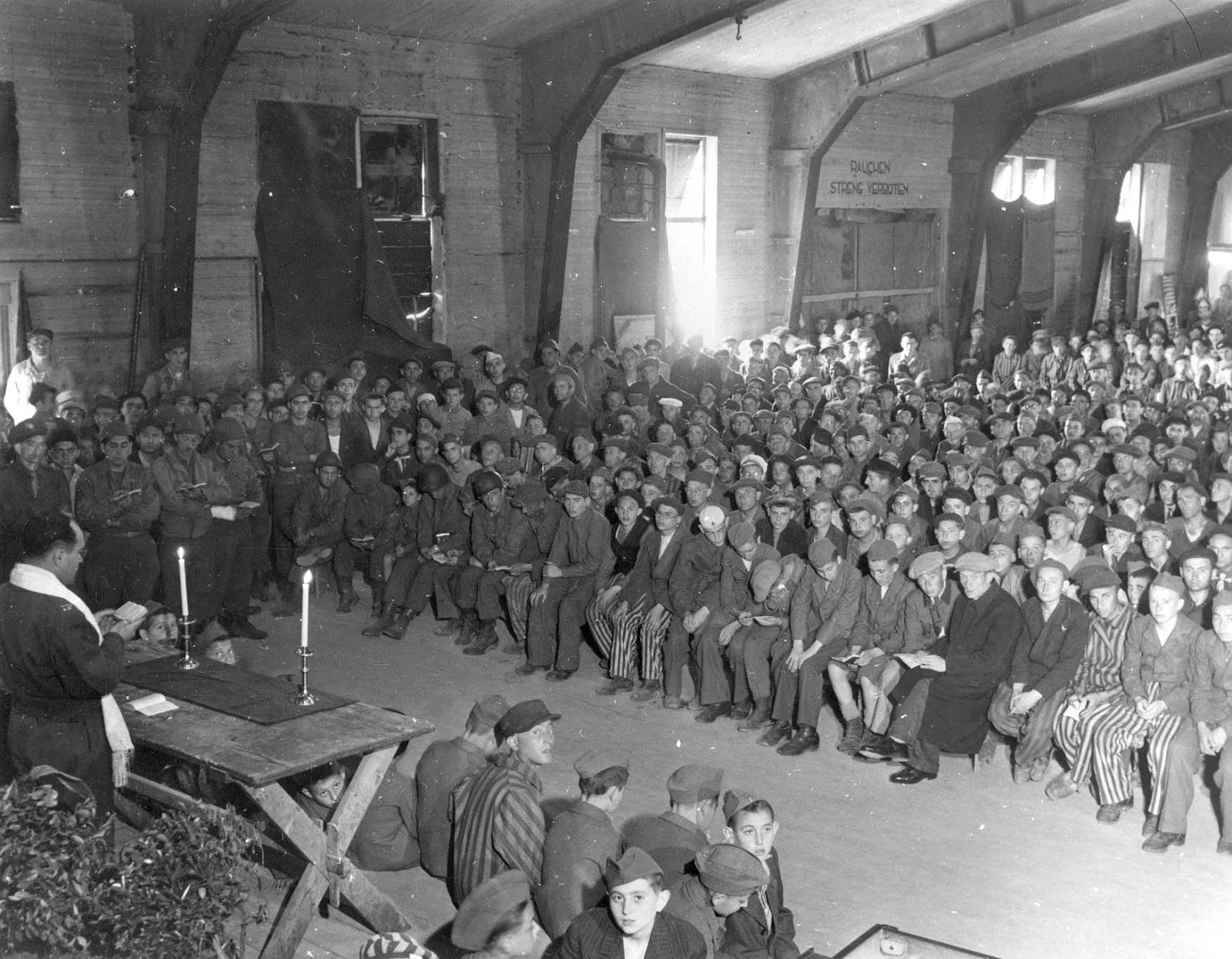

One of the first people to encounter the emaciated survivors was Rabbi Herschel Schacter (1917-2013), a young Brooklyn-born chaplain attached to General Patton’s Third Army. There is a famous photograph of him conducting services for hundreds of Jews in Buchenwald, probably taken on the first night of Shavuot.

One of the survivors who was there was Isaac Leo Kram (1921-2013). He later wrote about his Buchenwald experiences, and recalled what Rabbi Schacter had told them that night:

“[There will be] those who say, “I have suffered so much as a Jew until now, from now on I will cut myself off from my nation and from my religion!” …[but] do not despair and do not be quick to leave your people. Your personal fate is testimony to the fact that no person in the world can destroy our people. For thousands of years they have pursued us, in every generation they stand up against us to destroy us, and, nevertheless, we are alive! Believe in the eternity of our people! Place your hope in the eternity of the Jewish people – “the Eternal One of Israel does not lie” (I Samuel 15:29).”

Reading those words in a week during which the world’s most powerful nation formally recognized Jerusalem as the capital of the Jewish state while at the same time the terrorist group Hamas tried to overrun Israel by breaching the Gaza border so that a multitude of Palestinian murderers could run amok, I was struck by the fact that this counterintuitively optimistic streak is found at the heart of the Megillah we traditionally read during Shavuot.

The Book of Ruth is a confusing biblical text. Its inner meaning is obscured by the seemingly parochial nature of the storyline. Moreover, Ruth hardly seems like a dramatic tale of triumph in the face of adversity, like its counterpart, Esther. Nor is it a poetic or theological masterpiece, as are the parallel scriptural texts, Song of Songs and Ecclesiastes.

Besides, after reading through its four short chapters, one finds oneself wondering whether its lead character, Ruth, is demure and submissive, merely following her mother-in-law’s lead, or whether she is calculating and precocious, pushing all norms and boundaries to get what she wants. And what are we to make of her romantic conquest, Boaz? Or of the fact that this unlikely couple are the antecedents of the Royal House of David?

These, and various other puzzles, have preoccupied commentaries for millennia. The mere existence of the Book of Ruth as a separate narrative text in the Hebrew Scriptures is a clear indicator of its centrality in the the emergence of the Davidic monarchy, itself a primary component of Jewish identity, both in historical and contemporary terms. Getting to the core of who Ruth and Boaz are appears to be crucial if we are to truly understand the concept of a Messianic redeemer.

But rather than focus on the personalities of Ruth and Boaz, I would instead like to focus on a central character in the narrative who often gets overlooked, but whose role cannot be overemphasized.

I speak, of course, of Naomi – the impoverished widow of Elimelech, who returns home to Bethlehem after losing her husband and sons, only to discover that her late husband’s home and farmlands are no longer hers, as a result of the death of all the male members of her family. The only thing she has left are painful memories, and although she can count on the support of her devoted daughter-in-law, Ruth, this is tempered by the fact that Ruth is an outsider with little if any hope of ever becoming anyone’s wife and building a family and a future.

For all intents and purposes, Naomi is a woman whose life is over.

Naomi seems to be acutely aware of her plight, evident from her response to those who greet her by name as she arrives back in Bethlehem (Ruth 1:20):

אַל תִּקְרֶאנָה לִי נָעֳמִי קְרֶאןָ לִי מָרָא כִּי הֵמַר שַקַּי לִי מְאֹד “do not call me Naomi [‘pleasant’], call me Mara [‘bitter’], for God has made my lot very bitter.”

And yet, she never gives up, instead setting herself impossible aspirations. Although her daughter-in-law is from the despised Moabite nation, Naomi wants her to marry Elimelech’s nephew, Boaz, a wealthy landowner from the uppermost echelons of society. With quiet determination, Naomi sets the stage for this improbable “shidduch”, so that her misfortune can be reversed, and the hopelessness of her life replaced by success and meaningful hope for the future.

Confusingly, while her optimism and confidence seem utterly misplaced, her victory, when it occurs, seems almost inconsequential, certainly by comparison with stories like the one contained in the Book of Esther. In reality, however, the result of Naomi’s efforts is no less triumphant than the spectacular victory against Haman and his genocidal intentions.

The message conveyed by Naomi is that no matter how bleak one’s personal situation, one has to set one’s sights high, and then go for it. Not only can you succeed beyond your wildest dreams, but it is these kinds of triumphs that will result in a Royal House of David. This was what Rabbi Schacter meant when he spoke about the eternity of the Jewish people – and how right he was.

Anyone who survived the horrors of the Holocaust could easily have allowed their bitterness and destitution to swallow them up and disappeared without trace. But instead, they set their sights high, building new communities, schools, institutions – and even more remarkably, a country, Israel, that with all its flaws is the equivalent of a Royal House of David, itself not without flaws, but which nonetheless became a powerhouse of Jewish identity, synonymous with both our proud history, and with the ultimate redemption of mankind.

Photo: American chaplain Rabbi Herschel Schacter conducts religious services at the liberated Buchenwald concentration camp in 1945 (Public Domain)