THE SACRED AND THE MUNDANE

One of the most challenging tensions of human existence is the faultline between the sacred and the mundane. This quote, from the celebrated thirteenth-century Buddhist philosopher Dōgen Zenji (1200-1253), just about sums it up: “In the mundane, nothing is sacred. In sacredness, nothing is mundane.”

One way of resolving this conflict is by engaging in a process of drastic redefinition. As the beatnik pop philosopher Alan Watts (1915-1973) bluntly pronounced, “the mundane and the sacred are one and the same.”

On the face of it, this is exactly what the medieval Torah commentator Rashi appears to be saying at the beginning of Parshat Mishpatim, in his observation regarding the portion’s initial words – וְאֵלֶּה הַמִּשְׁפָּטים (“And these are the laws”). “Wherever it says, ‘these are’ [in the Torah], it separates what follows from the preceding section. But when it says ‘and these are’, this means that what follows adds something to whatever came before. This rule applies here… [the Torah is telling us that] just as the [Ten] Commandments were given at Sinai, the [laws in Parshat Mishpatim] were also given at Sinai.”

Rashi is addressing an obvious question. Mishpatim is almost exclusively focused on the most mundane laws imaginable, beginning with how one must treat a domestic servant, and going on to address the laws of homicide, kidnapping, assault, property damage, theft, rape, deception – and the list goes on. After the lofty events at Mount Sinai, culminating in a Divine revelation that remains the pinnacle of any Divine encounter ever experienced by humankind, the delivery of a dry list of civil laws, all of them ostensibly devoid of any kind of spirituality, is a major letdown – to say the least. But Rashi is undisturbed; these laws are just like the Ten Commandments, he says, because, to paraphrase, “the mundane and the sacred are one and the same.”

The problem with this idea – however wonderful it may sound – is that the mundane and the sacred are simply not one and the same. The ordinary tasks of life, the laws that govern society, the daily grind of human existence – none of these can possibly compare with the sublime experience of the Mount Sinai revelation, or the elevated moments of spirituality we all have from time to time, whether it is when we are praying, or on a Shabbat or festival. To even suggest that they compare seems disingenuous and forced, and unless there is a plausible explanation, one might dismiss Rashi’s explanation as mere rabbinic hyperbole with no practical application.

But there is a simple answer that resonates the moment you hear it. Dr. Tal Ben-Shahar is a former Harvard University professor of psychology who specializes in a field known as ‘positive psychology’. According to his research, even the most mundane and insignificant of tasks can be turned into something meaningful if they are consciously infused with greater meaning, such as when one connects them to personal values and goals.

A daily chore has no meaning in-and-of-itself, but if it is put into the perspective of broader goals – such as living in a tidy home or attaining a particular skill or reaching a specific target – it becomes greater than the sum of its parts. Of course, to achieve this state of mind, one must make the mundane tasks personally significant, so that they accord with our passions, instead of them being “dictated by our family, friends, workplaces or society.”

And although this may seem like a modern idea – one that chimes with the type of upbeat ‘self-help’ so ubiquitous in western society – in reality it is as ancient as Judaism itself. Moreover, in Judaism this idea is not just limited to personal goals and values; God is also introduced into the equation, until every aspect of a person’s life is elevated beyond mere human existence. And I believe that it is this idea which Rashi wishes to introduce to us at the beginning of Mishpatim: the mundane is not spiritual by default, rather the mundane can become spiritual by choice.

“Not everyone is a master of Jewish law,” wrote the late Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, “but spirituality is engraved in all our souls.” A profound observation, and while it may be true, it doesn’t quite convey the whole story. Because truthfully, one doesn’t need to be a master of Jewish law to experience the spirituality contained in those laws.

Indeed, it is no accident that the greatest aspiration of Jewish spirituality is not the study of mysticism, or even a focus on asceticism and devotional prayer, all methods that are common to other faiths. Instead – remarkably! – the greatest aspiration of Jewish spirituality is the devoted study of Jewish law in all its intricate details.

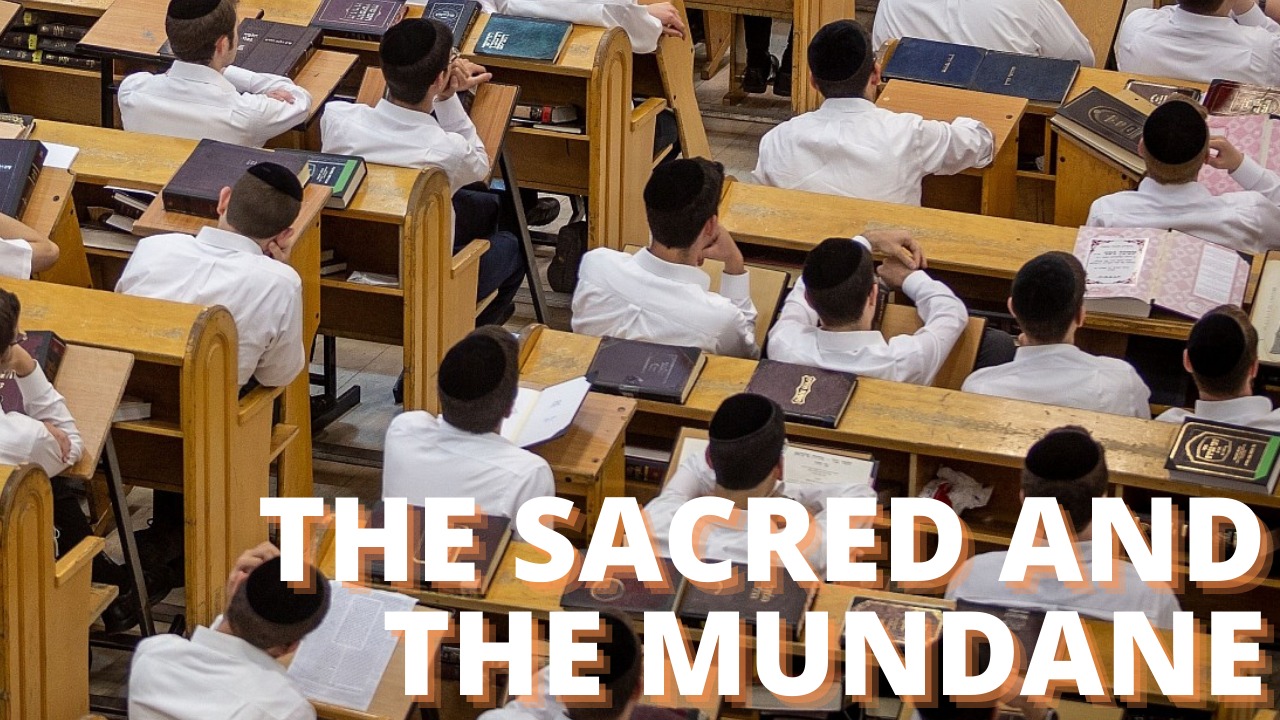

Anyone visiting a yeshiva study hall will immediately be struck by the enthusiasm and fervor of students studying Talmudic tractates that discuss the laws of damages, legal documents, oaths, and even the intricate laws of Shabbat observance. Most of these students will never be masters of Jewish law, but for all of them, the study of Jewish law is a sublime religious experience.

As Rabbi Sacks himself put it so strikingly: “The beauty of Jewish spirituality is precisely that in Judaism, God is close; you don’t need to climb a mountain or enter an ashram to find the Divine Presence.” And what could be closer than the ordinary aspects of Jewish life, namely the laws that govern how we exist as individuals, and how we coexist with those around us.

At the dawn of Jewish history, immediately after receiving the Torah, God conveyed this crucial message to His people – via the inclusion of a single letter ‘vav’ at the beginning of the next portion. God was telling His nation not to come down off the high of the Mount Sinai experience and settle back into the grind of ordinary life. Instead, said God, bring the spirituality of Mount Sinai into the most commonplace areas of your lives. And remember – nothing is ever routine if you make it special, and nothing will ever be mundane if you make it sacred.