THE REAL SECRET TO A RIPE OLD AGE

What are the chances of living to be over 100 years old?

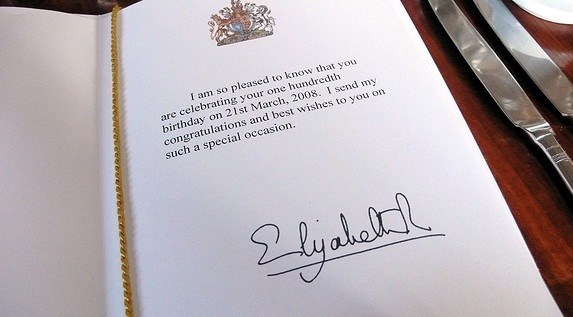

In the UK this milestone merits a congratulatory telegram from the Queen.

It is nearly a century since the British monarch started sending messages to British subjects who have reached the age of 100. In 1917, King George V sent a total of 24 celebratory messages to centenarians. By 1952 this had increased to 255, and in 2014 it had increased to 7,517.

As a result of this increase Buckingham Palace has had hire extra staff to deal with preparing and sending out the coveted telegrams.

In the United States average life expectancy is shorter than it is in the UK by a couple of years. The estimated number of centenarians in the US (none of whom have received a presidential acknowledgment, to my knowledge) is 72,000. The estimated number across the world is 450,000.

We are clearly living in a rapidly aging world, with the number of centenarians today roughly 90 times greater than it was a century ago. In the US the number of centenarians is expected to rise tenfold or more by the year 2050.

All of this has profound implications on retirement planning, healthcare, public pension policy, state economics, and more. Academics and actuaries are having a tough time keeping up with this evolving dynamic.

Until recently most calculations and projections defined people as ‘old’ once they had reached 65. In the majority of first-world countries age 65 is still the standard cutoff for everything, from pensions to healthcare systems, and is also the basis of a demographic measure known as the ‘old-age dependency ratio’. This term defines anyone over 65 as being dependent on the population aged between 20 and 65.

Recently, two researchers published a groundbreaking study that heralds the redefinition and recalibration of this whole arena. The study argues that the ‘old-age dependency ratio’ must be replaced with something that more accurately reflects the current reality.

Being 65 today is clearly very different from what it meant in 1950, and those who will be 65 in 2050 – of whom many more will live beyond 100 – will be very different to those who are 65 today.

The study suggests that planning for the future must reflect the fact that the aging process has profoundly changed, and while it may still be true that the heaviest healthcare costs kick in during the last years of one’s life, in the future this may happen in far greater numbers to people in their 80s or even 90s.

Which means that any existing paradigm that includes projections for the cost of healthcare for over 65s is probably inaccurate, and following those projections blindly leads to inflated insurance premiums, and worse. In short, we need to start again from scratch.

Another concern is the increase in the public pension age – something that is happening in many countries. While this phenomenon reflects the fact that people are working beyond 65, it is unfair that they can expect less money in retirement than their parents and grandparents received.

The study offers a solution for this and for other looming issues, but as I read through the study, it was not the solutions that interested me, but rather the underlying premise of the whole study. Clearly, it is not how long you live that matters, but what you do and how effective you are during the time you are alive.

It is this distinction that helped me understand a curious exchange the Torah portion of Vayigash.

When Jacob arrived in Egypt, Joseph introduced him to Pharaoh, who asked him a rather strange and irrelevant question (Gen. 47:8):

כַּמָה יְמֵי שְנֵי חַיֶיךָ – “how old are you?”

Jacob shot back with an extremely cryptic response:

יְמֵי שְנֵי מְגוּרַי שְלֹשִים וּמְאַת שָנָה מְעַט וְרָעִים הָיוּ יְמֵי שְנֵי חַיַי – “I have lived for 130 years, but the days of my life have been less, and extremely difficult.”

He then continued:

לֹא הִשִיגוּ אֶת יְמֵי שְנֵי חַיֵי אֲבֹתַי בִימֵי מְגוּרֵיהֶם – “the days of my life do not come close to the days of the lives of my forebears.”

Jacob understood that Pharaoh was not asking him about his age. Rather, Pharaoh had looked at this frail and elderly man in front of him, the father of his trusted viceroy, and had asked him pointedly: כַּמָה יְמֵי שְנֵי חַיֶיךָ – literal translation: “how many days are the years of your life?”

In other words, “you may be very old, and I may be much younger than you, but my short time here has been more valuable and productive than your lengthy life, as I am the omnipotent leader of Egypt.”

Jacob’s response was inspired. Real endurance is only ever achieved through fulfilling God’s purpose in the time we have allotted on this world, whether it is a short time or a long time. Material achievements are not the measure of one’s success, only spiritual productivity.

Regrettably, said Jacob, he had achieved less in the spiritual sphere than his forebears had, but by mentioning them he reminded Pharaoh that material achievement is ephemeral, and the only days worth counting are those devoted to one’s true purpose.

The definition of ‘old age’ may have changed dramatically, and people are certainly living longer, but a life is not measured in years, it is measured in how the days of each of those years are filled. How much time do we devote during our ‘days’ to achieving our true purpose – working on our relationship with God, and acting as his agents in any way that we can.

Even if we reach the ripe old age of 100, there might be people of 65 whose יְמֵי שְנֵי is far higher than ours.

Photo: Birthday greeting from Queen Elizabeth II sent on the occasion of a 100th birthday (www.royalcentral.co.uk)