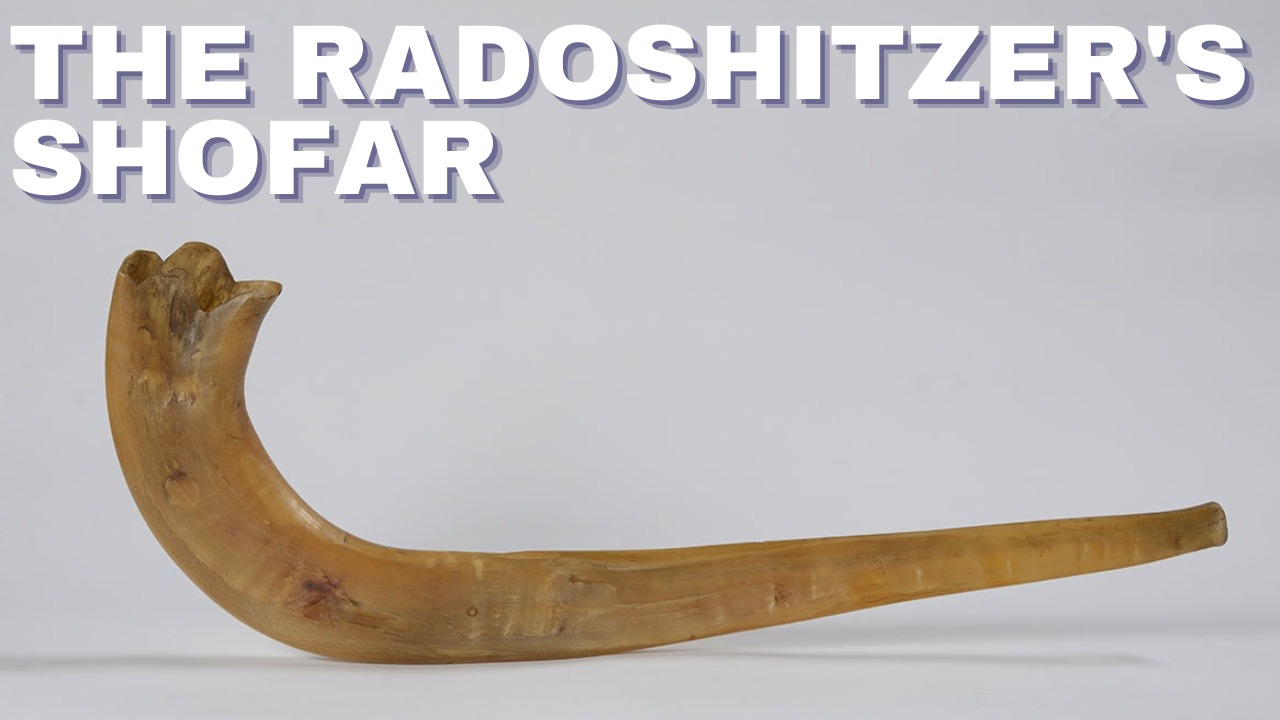

THE RADOSHITZER’S SHOFAR

Let me begin by posing a question. Then, I want to tell you a story. And hopefully, the story will answer the question – and will also offer some inspiration.

Here’s the question. The Talmud describes two types of sound that you need to hear from the shofar. One of them is the “tekiah” – a long straight uninterrupted sound. The second one is the “teruah” – a series of sounds: which could either be 3 medium-length sounds, or 9 or more staccato sounds.

The Talmud says that we must hear both kinds of sound from the shofar on Rosh Hashana, the tekiah and the teruah – and because there is a difference of opinion about the teruah sound, we need to hear various permutations and combinations of sounds so that we cover all the bases.

But here’s the thing. Every combination always has a tekiah at the beginning, and then a tekiah at the end. That’s the rule. Whatever sound or sounds are in the middle, whether it’s a shevarim, or a teruah, or a shevarim/teruah – before them you must have a tekiah, and afterward you also have to have a tekiah.

It seems strange. If you must hear a tekiah and a teruah, just do a tekiah, and then a teruah. Or do the teruah first, and then the tekiah. Why do you need the teruah sound to be preceded AND followed by a tekiah? What’s the message?

Let me park that question for a minute and tell you the story of the Radoshitzer shofar. The story centers around a young pre-war yeshiva bochur from the city of Piotrkow in Poland. His name was Moshe Weintreter, and he came from a family of Radoshitzer Hasidim. I’d be surprised if you’ve ever heard of the Radoshitzer Hasidic group. It’s one of those Hasidic dynasties that thrived in prewar Poland, but which was utterly wiped out by the Holocaust.

The Rebbe of Radoshitz in the period just before and during the Holocaust was a man called Rabbi Yitzchak Shmuel Eliyahu Finkler (1892-1944). He was a relatively young man, in his late 40s, when the war broke out – but he’d been the rebbe since the age of 20, as his father died in 1912.

The Piotrkow Jewish community, where Rabbi Finkler led his followers, was a wonderful community. It was affluent and successful. There were thriving shuls, schools, yeshivas, social welfare organizations – it was a model community, and life for Jews in Piotrkow was great. Then, the Second World War began – and everything changed overnight.

Life was cheap, poverty was everywhere, and danger lurked behind every door, and on every street. But there was money, and gentiles took bribes and hid Jews, or turned a blind eye to Jews in hiding in exchange for money and valuables. Still, the Nazis were resourceful and eventually, even the Jews in hiding were caught and sent to their deaths.

In 1943, after years of evading capture and doing everything they could to avoid being killed, both Moshe Weintreter and Rabbi Finkler were deported along with thousands of other Piotrkow Jews, many of them straight to extermination camps. But the rebbe and young Moshe were spared certain death by being sent to the forced-labor camp in Skarzysko-Kamienna. Although, while it may not have been a death camp – thousands of Jews died there, or were killed.

Rabbi Finkler was an inspirational figure, a lightning rod of faith and hope. He was undeterred by any danger and totally determined to stay as Jewishly observant as possible, even amid the dangers of Nazi tyranny and vicious brutality. He made minyanim every day for shacharit, mincha and maariv, and he inspired people with words of encouragement and optimism.

Then, as Rosh Hashana of 1943 approached, the rebbe could speak about nothing else but blowing shofar. He yearned for a shofar. He had managed to smuggle some diamonds into the camp, and he used them bribe a Polish guard to get him a horn to turn into a shofar. But the first horn the guard brought turned out to be an ox’s horn – which is not kosher to be used as a shofar. The rebbe didn’t give up. He found another diamond or two, and eventually the Polish guard brought him a ram’s horn.

The rebbe now sought out his young protégé, Moshe Weintreter, who had secured a role as a metal worker, and was working in the metal workshop at the labor camp. The Radoshitzer Rebbe handed him the ram’s horn – “Turn it into a shofar,” he said. Moshe was very taken aback. He’d never made a shofar in his life.

The rebbe saw that he was surprised. “If you complete this task,” he told Moshe, “the merit of doing it will safeguard you – you will survive this hell, and make it out alive.”

Making a shofar isn’t simple. First, the ram’s horn has to be flattened and softened so that it has a long thin section to blow into. Then it needs a turned-up wide opening at the end, to amplify the noise. You have to heat the raw horn gently so that you make a hole from the tip of the horn to the hollow part inside the horn, and you have to make sure you don’t crack it while you’re working with it.

Moshe Weintreter – who had never made a shofar in his life – worked on the horn secretly, for days, perhaps weeks, hiding it so that he wouldn’t be spotted. Eventually, the shofar was ready, and he brought it to the Radoshitzer Rebbe just before Rosh Hashana.

As incredible as it seems, on Rosh Hashana in 1943, at the Skarzysko-Kamienna labor camp, in the fourteenth barrack building, the Radoshitzer Rebbe gathered together a group of the faithful and he blew shofar for them. It was a moment of pure spirituality and inspiration.

Within a couple of months, Weintreter was taken to do metal work at another camp, in Czestochowa. He insisted on taking his toolbox with him – and hidden in a secret compartment under the tools he stashed his precious shofar. He managed to keep it safe, until one day, towards the end of the war, he was randomly picked up and deported to Buchenwald. He didn’t have a chance to take his shofar, and it remained hidden in the toolbox in Czestochowa.

Moshe Weintreter survived the war, just as the Radoshitzer Rebbe promised him he would. His family was wiped out, but he survived. Sadly, the Radoshitzer Rebbe died, of malnutrition, just three months before liberation.

After he was liberated, Weintreter went from Buchenwald to Italy, where he helped organize the illegal immigration of Jews by ship to Palestine. He changed his surname to Ben-Dov, and he got married to Ida, a fellow Holocaust survivor. They moved to Israel and settled in Bnei Brak. But Weintreter never forgot about his shofar; his constant dream was to honor the memory of Rabbi Finkler, the Radoshitzer Rebbe, by somehow bringing it to Israel.

Over the years, Moshe wrote to anyone he could think of who might have found it and described the shofar to them. Unbelievably – after decades of searching – he received a letter from someone who knew where the shofar was. Apparently, almost immediately after the war the shofar was discovered in Czestochowa, in the exact hiding place where Moshe had left it, and it was given to the local Jewish community.

Later that year, a visitor came to Czestochowa from the United States. He was a prominent Yiddish author and journalist – and the community gave him the shofar as a gift. Weintreter tracked down the family of that visitor, and once they heard the story they were only too happy to reunite the shofar with the person who had made it. And so, in 1977, Moshe Weintreter got his shofar back and he gave it to Yad Vashem – where it is now part of the permanent exhibit.

Moshe Wintreter passed away some years ago, and so did Ida – but they left a wonderful family. Their son is Shmuel Ben-Dov, a retired banker who lives in Bnei Brak. And when Shmuel’s youngest son went to Yad Vashem together with his IDF officers training class, he showed his fellow trainee officers his grandfather’s shofar, which was miraculously fabricated in the metal works of Skarzysko-Kamienna labor camp and used there in 1943.

What a story. But it is more than just a story about a random shofar, or some Holocaust miracle. It is a story about a shofar that is emblematic of exactly the sounds we blow out of the shofar on Rosh Hashana.

Moshe Weintreter’s life started out in Piotrkow with a tekiah – calm, straightforward, and uncomplicated.

But then his life when through every teruah possible. It was broken and shattered.

And finally, he came to Israel – and there was a tekiah again. The brokenness was gone, and the calm came back.

And that is exactly the message the shofar wants to convey. We go through hard times, as everyone does, and we think to ourselves – before things were tough, we had it so good!

The sounds of the shofar act to reassure us – don’t worry, good times always follow bad times. Just like you had a tekiah before, there’s going to be a tekiah afterward. The shevarim, the teruah, they are just for now. Listen to the shofar, pray for salvation and redemption, and the tekiah will surely follow.

Image above: the Radoshitzer’s shofar, on permanent display at Yad Vashem museum in Jerusalem.

Moshe Weintreter Ben-Dov, who made the Radoshitzer’s shofar in 1943