THE MESSAGE OF THE HOLY HUNCHBACK

There is no question that the primary focus of Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur, as well as the intermediate days, is “teshuva.” Usually translated as “repentance,” the actual translation of this Hebrew word is “return” – and that’s what it means: we actively seek a return to our full relationship with God by going through a process of repentance.

But while this period in the Jewish calendar is dominated by penitential prayers and a strong emphasis on ritual, Maimonides firmly reminds us in his seminal Laws of Teshuva that before seeking to refresh your relationship with God, you must first fix broken relationships with fellow humans.

Religious fervor and spiritual devotion have no meaning if you can’t get on with the people around you, and it’s pointless trying to reconcile with God if you have made no effort to reconcile with those you have offended, harmed or mistreated during the course of the last year.

But I would like to take this idea a bit further, and to illustrate it via one of the late Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach’s most inspiring stories. I heard the story from him many times, and with each retelling it made a deeper impression. Even now, decades after I first heard it, I marvel at the simplicity of its message, and profundity. Based on a random encounter Rabbi Carlebach had with a student of Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira of Piaseczno (1889-1943), the story teaches us that it is never sufficient just to fix broken relationships, but rather one must focus on constantly doing kindness for others.

Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira of Piaseczno was a great Hasidic leader who found himself trapped in the Warsaw ghetto during the early years of the Holocaust. During his time there, despite the horrific and ever-worsening conditions, Rabbi Shapira regularly delivered inspiring homilies and sermons, boosting the faith of the faithful, and encouraging hope among the hopeless. All along he carefully recorded the homilies on scraps of paper, in the hope that one day he would be rescued, and they would be published.

Eventually it became evident that the end was nigh, and Rabbi Shapira gave the manuscript material to the Polish-Jewish historian, Emanuel Ringelblum (1900-1944), who created the Warsaw Ghetto “Oneg Shabbat” archives – a bunch of tin canisters that contained a comprehensive assortment of ghetto-related documents which were buried underground before the final deportations.

The canisters were discovered in 1946 during Warsaw’s reconstruction, long after all the ghetto inhabitants had been murdered by the Nazis. Among the countless documents in the archives was the Piaseczno Rebbe’s manuscript, and it eventually found its way into the hands of one of Israel’s most dynamic Religious Zionist activists, Baruch Duvdevani (1916-1984), who published the homilies under the title Eish Kodesh (“Sacred Fire”) in 1956. This book remains one of the most powerful religious documents to emerge from the darkest depths of the Holocaust, a testament to maintaining one’s faith amid cruelty and crisis.

Before the Second World War, Rabbi Shapira was best known as a master educator. He had presided over a yeshiva of pre-barmitzva boys, and would proudly say – with a twinkle in his eye – that he was unlike any other Rebbe in Poland: “My Hasidim all eat on Yom Kippur,” he would quip, “because they are not obligated to fast!” Thousands of children attended his yeshiva over the years, but all remnants of his sect were swallowed up by the Holocaust, and very few of his followers survived.

After Rabbi Carlebach read Eish Kodesh he became obsessed with meeting one of the boys who had studied at the Piaseczno Rebbe’s yeshiva – but despite his efforts to locate them, it seemed that they had all been killed.

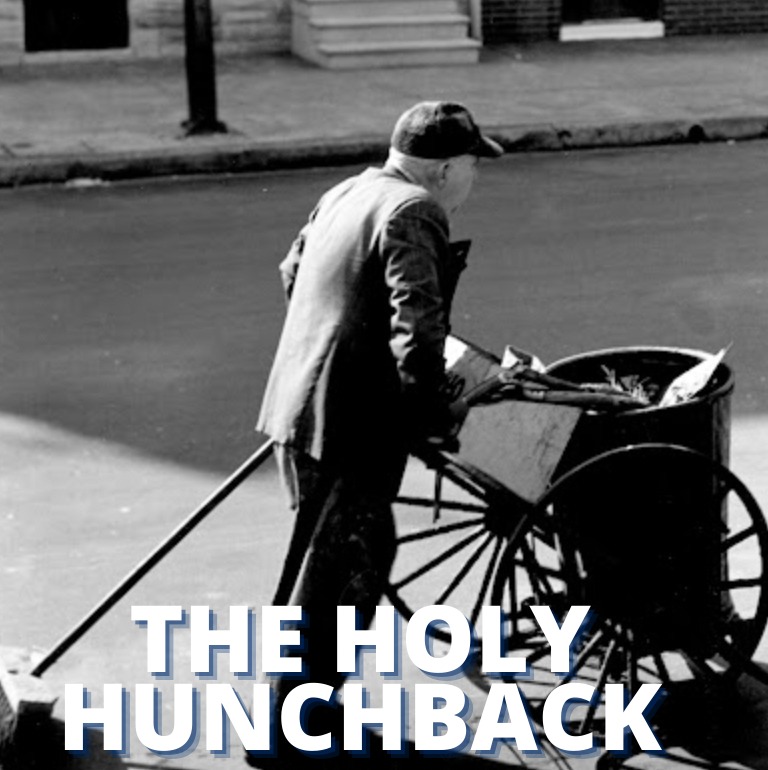

Then, one day in the early 1970s, he was walking down Rehov HaYarkon in Tel Aviv and noticed a hunchbacked streetcleaner sweeping the sidewalk. Rabbi Carlebach was always drawn to people on the fringes in his desire to lift their spirits, and he greeted the streetcleaner. The man answered him in a Polish-Yiddish accented Hebrew.

“Where are you from?” Rabbi Carlebach asked. “I’m from Piaseczno.” “Really? Piaseczno? Did you know the holy rebbe Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman?” “Of course,” said the man, “I studied at his yeshiva from the age of five until I was eleven.”

The streetcleaner leaned on his broom; he had a faraway look in his eyes. “That was when the Nazis took me to Auschwitz. When I was eleven. I was very tall for my age – they thought I was seventeen. I was very strong, but I didn’t always follow orders. I would get terrible beatings – that’s why I look like this. I always recovered, but the damage from Auschwitz is permanent. Look at me now, my body is a wreck. And now? I have nobody in the whole world. Everyone in my family was killed, no one would marry me, I have no children. And that’s my life.”

Rabbi Carlebach was stunned. “I’ve always wanted to meet one of Reb Kalonymus Kalman’s students. Please, I’m begging you, do me this kindness – can you tell me one of the teachings that the Rebbe taught you in yeshiva?”

The hunched streetcleaner began sweeping again. “Do you really think that after five years in Auschwitz I remember any teachings?” He gave a hollow laugh.

Rabbi Carlebach was undeterred. “Yes, I do think so. The words of such a holy man never disappear – they penetrate you forever.”

The man stopped sweeping, and looked at Rabbi Carlebach – a deep, penetrating gaze. “Do you really want to know?” he asked.

“Yes,” said Rabbi Carlebach, “and I promise with all my heart that whatever you tell me I will repeat all over the world.”

And so, this is what the streetcleaner from Piaseczno told Rabbi Carlebach in Tel Aviv that day.

“There will never be a Shabbes like the ones we had with the Rebbe in Piaseczno. At the Kabbolas Shabbes prayers, hundreds – and sometimes thousands – of children were dancing around the Rebbe, who stood, beaming, like a king, at the center of all the circles. The Rebbe made kiddush – and we all hummed with him. The amens were incredible. Throughout the meal he would teach Torah, and he would always say: ‘Kinderlech, taire kinderlech, my most precious children, always remember and never forget – the greatest thing in the world is to do someone else a favor.’

“By the time I arrived at Auschwitz, my whole family was dead, and I wanted to kill myself. But each time I was about to do the deed, I would hear the Rebbe’s voice: ‘always remember and never forget – the greatest thing in the world is to do someone else a favor.’

“Do you know how many favors you can do in Auschwitz? With people dying all around you, people crying, beyond despair. Most of the inmates who had any strength were just concerned for themselves. But I stayed up all night, comforting people, finding scraps of food for the weakest, trying to cheer people up. And whenever I wanted to end it all, suddenly I would hear my Rebbe’s voice again.

“Even here in Tel Aviv, I’m all alone – there are moments when I’m ready to finish myself off. One time I went into the sea up to my nose in the water. But there was the Rebbe’s voice again. I can always find someone to help. And that’s what I do. I’m still doing favors, I’m still alive, I’m still a student of my Rebbe, I’m still a good Jew.”

The streetcleaner patted Rabbi Carlebach on the shoulder: “My friend, that’s the teaching: ‘always remember and never forget – the greatest thing in the world is to do someone else a favor.'” And with that, he picked up his broom and went back to his sweeping.

This encounter took place just before Rosh Hashana. After Sukkot, Rabbi Carlebach came back to Rehov HaYarkon to look for the streetcleaner, but he was gone – apparently he died suddenly on the second day of Sukkot.

Rabbi Carlebach stayed true to his word, and repeated the teaching of the Piaseczno Rebbe at countless concerts and gatherings. The message of the “Holy Hunchback” – as Rabbi Carlebach called him – had to live on. “Always remember and never forget – the greatest thing in the world is to do someone else a favor.” Or, to put it more bluntly, your relationship with God must always be preceded by kindness and consideration for others, otherwise life is simply not worth living.