THE MARK OF TRUE LEADERSHIP

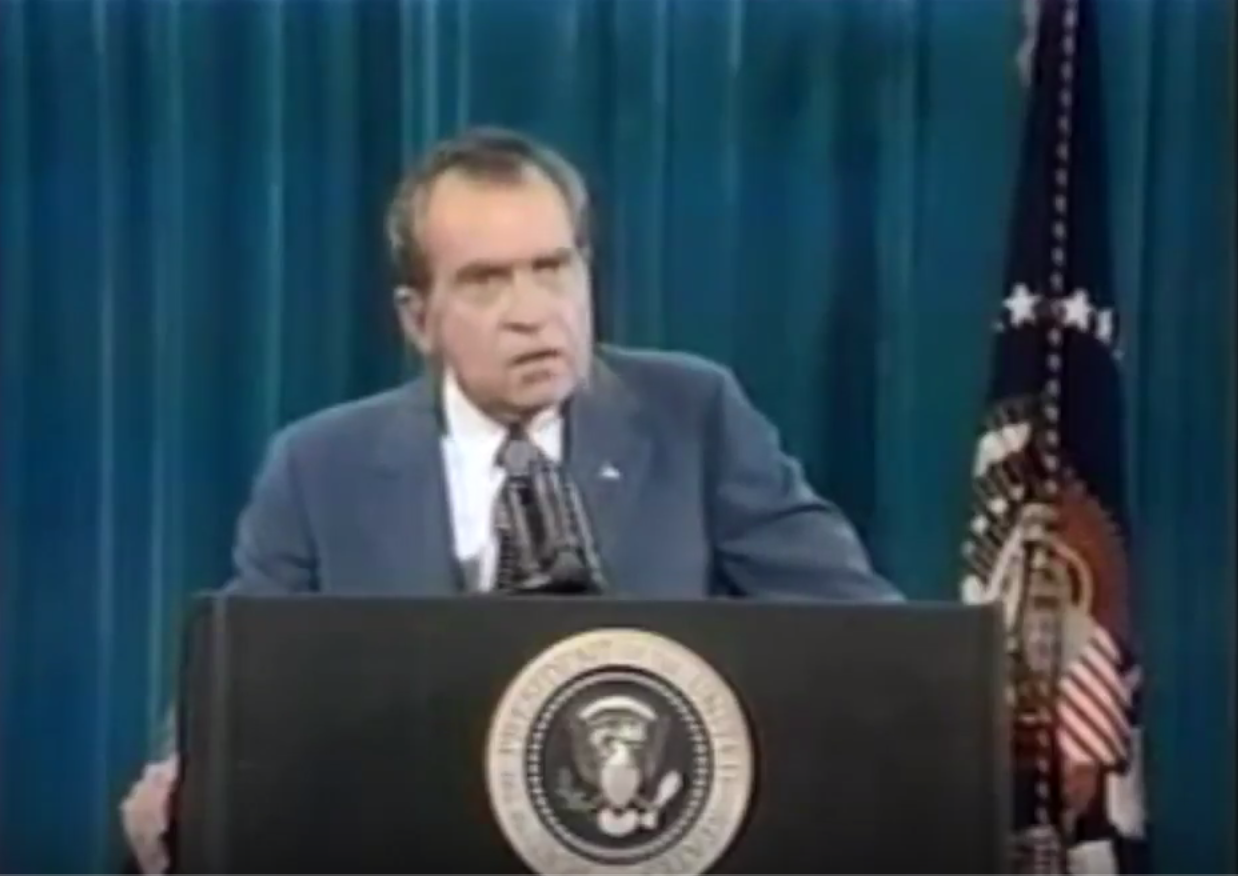

On November 17, 1973, 400 Associated Press managing editors gathered in Orlando, Florida, to meet beleaguered President Richard Nixon for a nationally televised press conference.

The entire country was captivated by the dramatic events unfolding on an almost daily basis, in the saga that had become known as the “Watergate Crisis”.

What began in the Summer of 1972, with the botched robbery by bungling thieves of a political campaign office, had resulted in the stunning arrest of some of the administration’s loftiest officials, and there was widespread public dismay at the grubby self-interest of those charged with leading the nation. This press conference had been sought by Nixon, and was understood by everyone as being of critical importance.

If Nixon was able to defend his record, and articulate cogently why the public should give him their trust, everybody agreed that the crisis would fizzle out. If, on the other hand, he was unable to present himself as a credible leader, the road to his impeachment or losing the presidency before the end of his term was more-or-less guaranteed.

The press conference was intense. It went on for over an hour, with a barrage of question after question. The president was calm, coherent, and even humorous at times. Then, about halfway through, he was asked about possible irregularities in his personal finances, with the next questioner querying how, as chief executive of the administration, he could have allowed something like the Watergate affair to occur.

After answering the questions separately, offering a fairly detailed defense of both his financial affairs and his record as president, Nixon offered a conflated answer to both questions that he felt would present, in a nutshell, why the focus on him was both unfounded and unfair.

“I [have] made my mistakes, but in all of my years of public life, I have never profited […] from public service. I have earned every cent. And in all of my years of public life, I have never obstructed justice […] people have got to know whether or not their President is a crook. Well, I am not a crook.”

His underlying thesis was simple. In the same way that he was fully transparent in his financial affairs, and it was clear that he done nothing illegal or even shifty in that sphere, his role in Watergate was equally pure, and his hands were completely clean. He was not, as he declared, a ‘crook.’

This statement became the most quoted phrase in all of the following day’s news reports, and it was a statement that would haunt Nixon for the rest of his life.

The British journalist, David Frost, who famously interviewed Nixon two years after he left office, recognized that it was at this exact moment that Nixon’s fate was sealed. The American people had wanted to see leadership. What they saw instead was a facile claim of innocence by association.

At the end of three grueling days of interviews, Frost sought, and incredibly received, an acknowledgment by the ex-President, that his stubborn inability to admit fault and to shoulder responsibility in the Watergate affair had been an egregious crime against the citizens of the United States.

In fact, many saw this weakness of character as worse than anything related to the original sin of Watergate, and even the subsequent cover up.

This insight into Nixon’s downfall, in a reverse logic sort of way, helps us understand one of the most troubling chapters in all of Genesis – the story of Judah and Tamar. The inclusion of this episode in the Torah is usually understood in the context of showing the importance of owning up to wrongdoing.

After being challenged by his erstwhile daughter-in-law, Tamar, in such a way that avoiding responsibility was an easy option, instead of obfuscating and mitigating his actions, Judah declared (Gen. 38:26):

צָדְקָה מִמֶנִי “she has right on her side.”

He admitted, publicly, that he was guilty of having prevented her from having children, as had been his duty.

But while it took great courage to admit fault, this still does not explain why we need to know that Judah was capable of such an admission. This only becomes clear much later on, when Jacob gathers his sons around his deathbed in Egypt.

Reuben, Simeon and Levi, Jacob’s three oldest sons, are passed over for the eternal leadership of the Jewish nation, in favor of Judah, not only as a result of their inherent faults, but also because Judah had the unique quality we all seek and hope for in our leaders – the courage to own up to mistakes.

In the episode with Tamar we see a powerful man with, it seems, everything to lose if he shows weakness, admit to wrongdoing – even though he could have easily covered it up. That is genuine greatness, and that is the mark of true leadership.

It was a family trait, and it continued through the generations, down to King David, and his son King Solomon. And ultimately it will be the reflected in the leadership of their descendent, the Messianic redeemer.

We mistakenly understand leadership as being purely about the ability to inspire, or delegate, or come up with powerful ideas and put them into action. But a real leader is not only capable of those things, but is also someone who is humble in the face of his own weaknesses.

Photo: Richard Nixon addresses 400 Associated Press managing editors at a press conference on November 17, 1973 — “I am not a crook!” (YouTube)