THE LEGEND OF RABBI AMNON RECONSIDERED

Unlike every other major and minor Jewish festival, Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur are not connected to a narrative counterpart.

There is no exodus from Egypt or Sinai revelation, nor are there quaint wilderness dwellings. There are no villains to speak of – no Pharaoh, Haman or Antiochus; nor are there any heroes for us to celebrate, such as Moses, Esther and Judah Maccabee.

It is a vacuum that leaves us with almost nothing to arouse historical meaning during this critical period in the Jewish calendar. I say ‘almost’ because we do have the jarring story of Rabbi Amnon of Mainz, author of the prayer often cited as the one that truly captures the mood of High Holidays – Unetaneh Tokef.

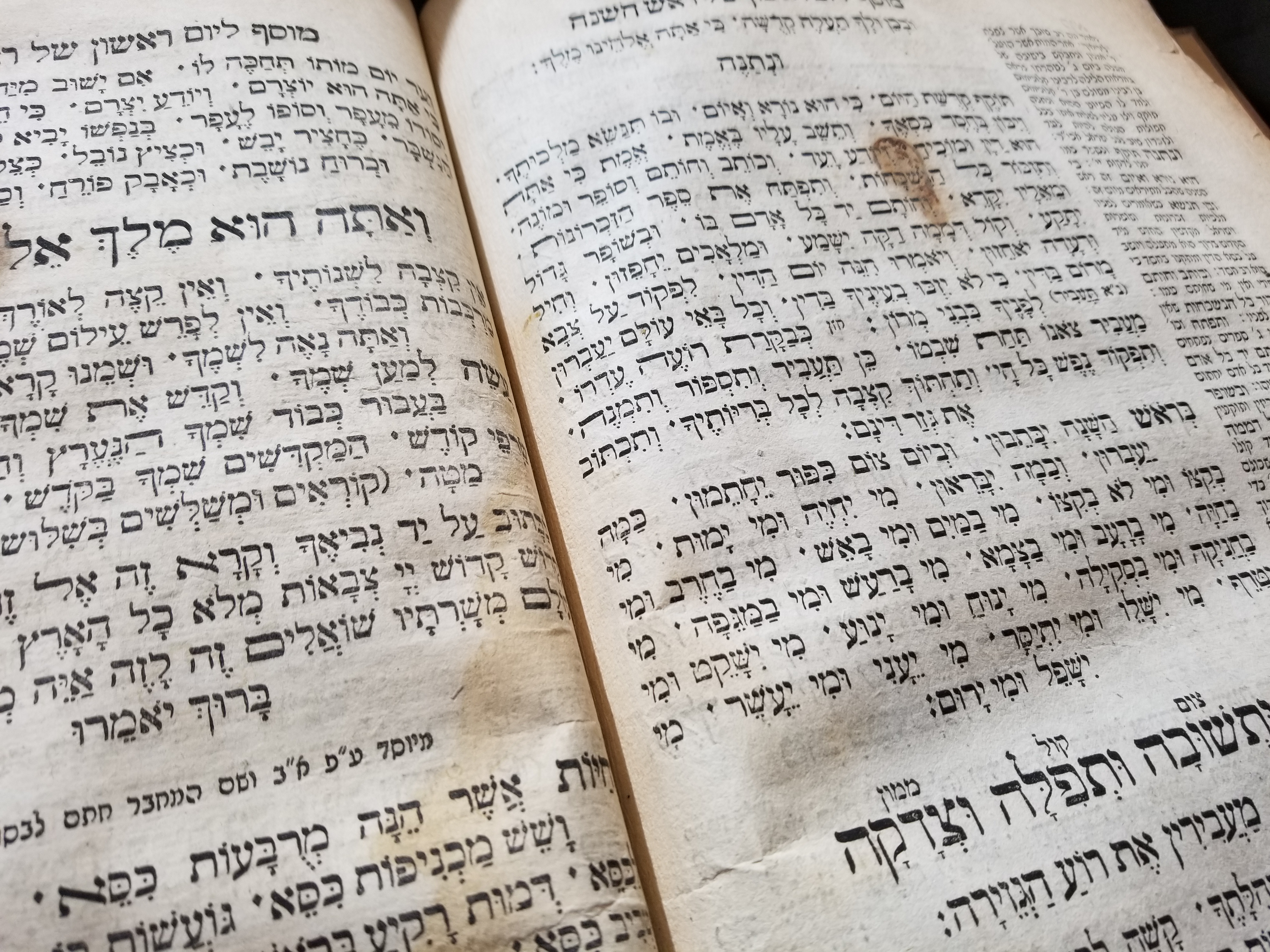

Recited congregationally at a high point in the prayers, and then repeated by the cantor using one of the numerous haunting compositions that have emerged from various liturgical traditions, Unetaneh Tokef is an emotional supplication which encapsulates the urgency of Yamim Noraim.

Rabbi Amnon’s story was first recorded in the thirteenth century by Rabbi Isaac ben Moses of Vienna in his influential Ohr Zarua, a work that chronicles the rites and customs of German Jewry which went on to become a primary source of Ashkenazi customs. Rabbi Isaac quotes Rabbi Ephraim of Bonn, an earlier rabbinic luminary most famous for his accounts of the Crusader persecutions against Jews in his own day, who in turn named Rabbi Amnon as the author of this prayer.

Rabbi Amnon’s story takes place the early eleventh century, more than one hundred years before Rabbi Ephraim was born. At the time, Rabbi Amnon was a leading Rhineland rabbi who maintained a warm relationship with the local archbishop.

The two religious leaders often met with each other, and among other things would engage in theological discussions and debates. At first these discussions were innocuous, but they eventually developed into attempts by the archbishop to convert Rabbi Amnon to Christianity.

Rabbi Amnon continuously resisted the conversion pressure, until on one occasion, feeling more intimidated than usual, he asked to be given three days to think about it.

As soon as Rabbi Amnon arrived home he regretted his response, and decided not to return to the archbishop with an answer. After a few days the archbishop had Rabbi Amnon arrested and brought to him in chains, whereupon the rabbi requested that his tongue be cut out for having misled the archbishop.

The archbishop dismissed this suggestion, and instead offered Rabbi Amnon the choice of conversion or dismemberment. The pious rabbi resolutely refused to convert, even as his limbs were removed one by one. Mutilated and in pieces, he was sent home to die.

It was Rosh Hashana morning, and Rabbi Amnon directed those transporting him to take him to the synagogue. A horrified hush gripped the community as his brutalized body was brought inside the sanctuary. It was just before the kedusha prayer during mussaf, and Rabbi Amnon began to compose a Hebrew prayer that described the awe-inspiring atmosphere of High Holidays, when we endeavor to reestablish our commitment to the principal ideals of our faith.

Although Judaism maintains that God is omnipotent, He has a personal relationship with each one of us. On these days, said the dying Rabbi Amnon, our fate is decided: מִי יִחְיֶה? וּמִי יָמוּת? מִי בְקִצוֹ? וּמִי לֹא בְקִצוֹ – “Who will live? Who will die? Who [will die] in the proper time? Who [will die] before their time?”

With his last breath, Rabbi Amnon proposed the only three things that can alter our fate: “repentance, prayer, and acts of kindness.” And then he was gone.

The following year, Rabbi Amnon appeared to his colleague Rabbi Kalonymus ben Meshullam in a dream, and insisted that Unetaneh Tokef be insterted into the liturgy.

Thereafter, Rabbi Amnon’s tragic deathbed story became a staple narrative accompaniment to the High Holidays, heavily featured in sermons and festival prayer books. The implied lesson was that Rabbi Amnon realized too late that his grisly fate had been decided on Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur of the previous year, at a time when he had felt no threat from his friend the archbishop. He composed the prayer and insisted on its permanent inclusion to warn us against the hubris of complacency in the face of destiny, and to fire us up in anticipation of the unexpected.

But while this is both a wonderful lesson and appropriately timed, the legend of Rabbi Amnon is exactly that – a legend. Despite our detailed knowledge of rabbinic leadership in the Rhineland during this era, there is absolutely no record of a Rabbi Amnon in Mainz, or anywhere else for that matter.

Additionally, the torture and death of Rabbi Amnon bear remarkable similarities to the martyrdom story of the seventh century Catholic saint, Emmeram of Regensburg.

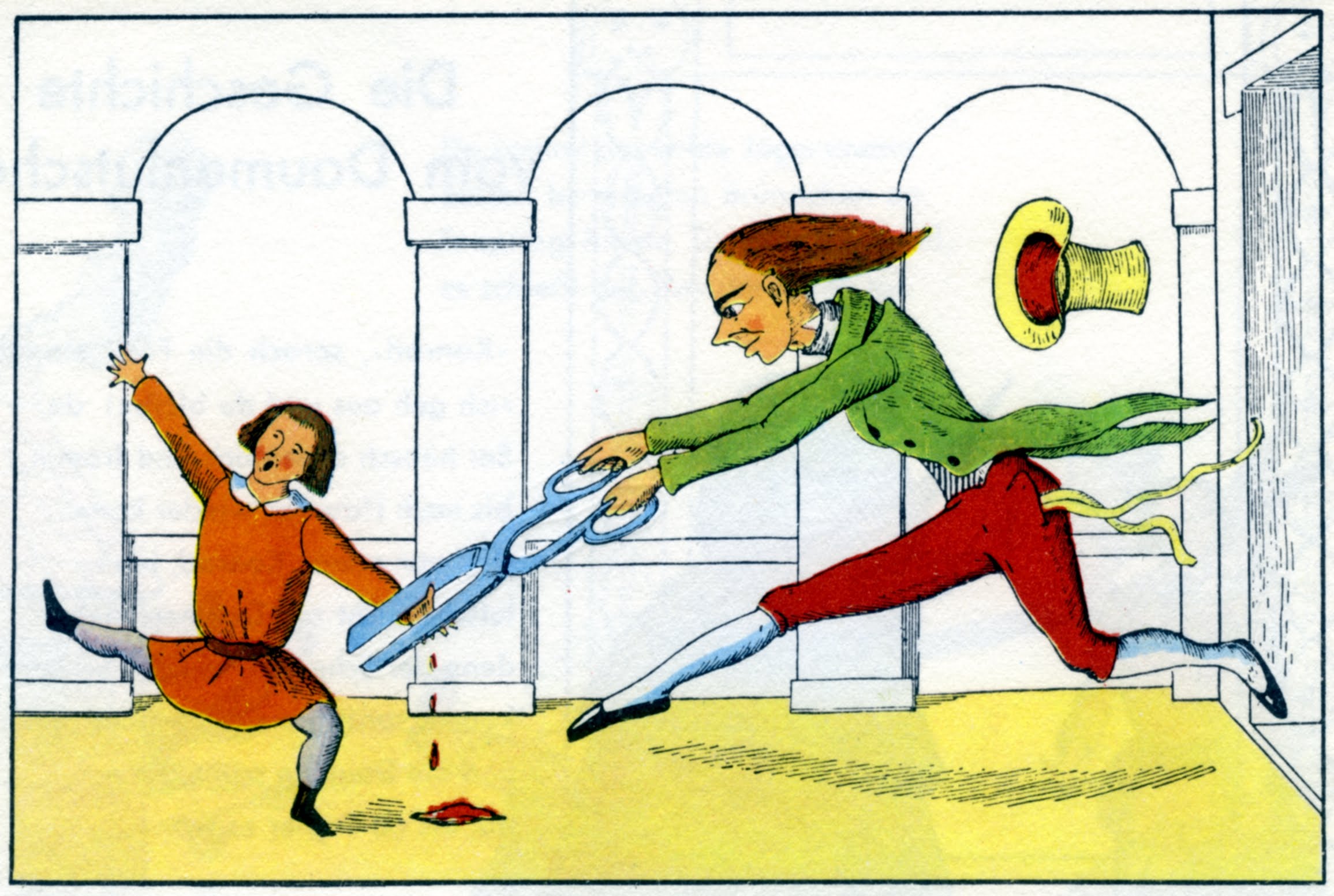

Traditional German folklore is full of stories which include shocking and gratuitous violence. As recently as the nineteenth century, the Struwwelpeter moral lessons short-story collection for children included the alarmingly violent Die Geschichte vom Daumenlutscher, in which a mother warns her son not to suck his thumbs, and after he disobeys her a roving tailor comes along and cuts off his thumbs with a giant pair of scissors. The rest of the stories in the collection are similarly grotesque.

Clearly the Rabbi Amnon story dovetails with a familiar literary genre. It was also recorded for posterity at a time when German Jewry was reeling from Crusader atrocities against Jews. What is certain is that it has nothing whatsoever to do with the composition of Unetaneh Tokef, a fact that was proven beyond any doubt when the very same prayer was found in an eleventh century middle-eastern Cairo Genizah fragment.

But while I will leave it to others to speculate on the origins of both the prayer and the strange legend of Rabbi Amnon, rather than finding this iconoclastic myth-busting revision disturbing, I actually find it quite liberating.

As it turns out, Yamim Noraim were never meant to be associated with stories and legends. Unlike other festivals where stories evoke the mood of the day, on Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur they would be nothing but a distraction.

On these Days of Awe, we reflect on our lives and future unencumbered by literary gimmicks and narrative crutches. Rather we consider simple questions – “Are we connected to God?” “Will we live?” “Will we die?”

Hopefully, we will merit answers that bode well for us, our families and our communities, and we can look forward to a wonderful year ahead.