THE IMPORTANCE OF PERSONAL PAIN

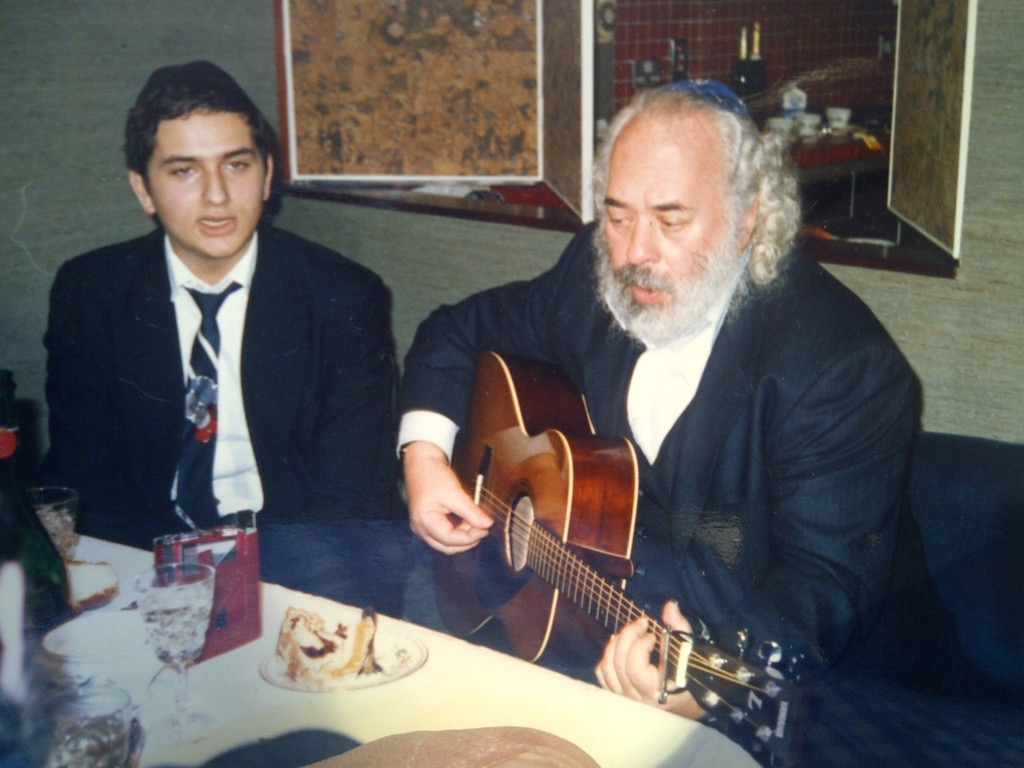

The late Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach was a wonderful raconteur, who would regale audiences around the world with his inspirational tales of Hasidic masters.

As he once told me, while not every one of his stories was true, all of them were important.

I recall him telling the following story, and I’ve repeated it many times. Oddly enough, I have a feeling that this one is true — but before I tell you

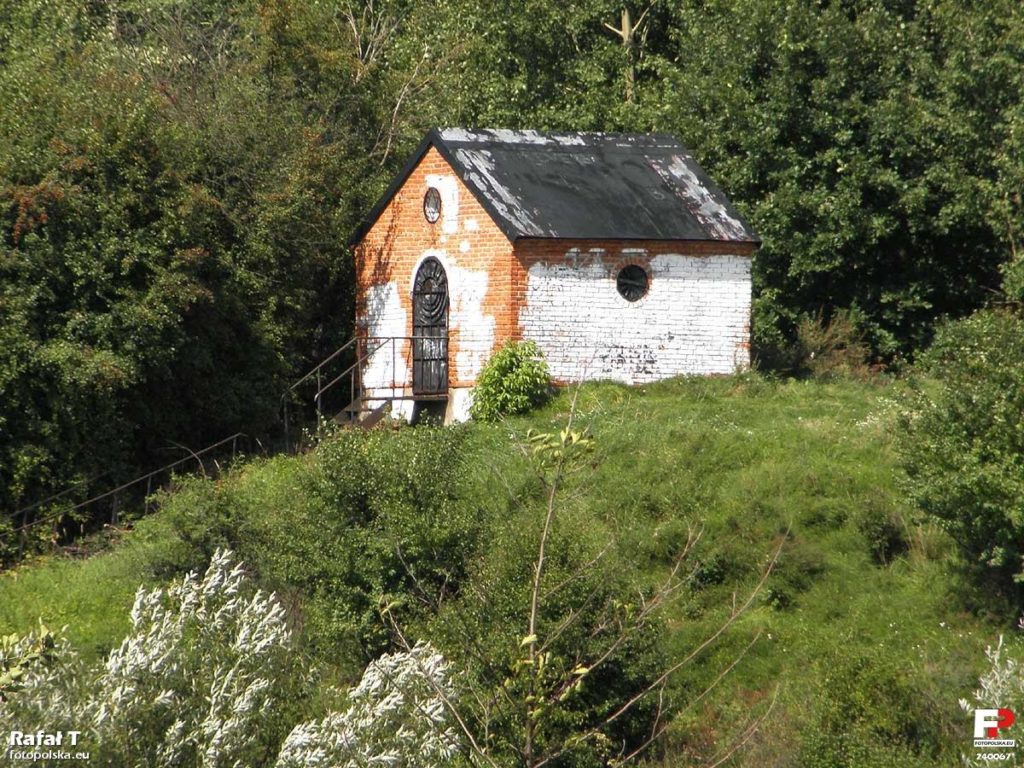

A man once came to visit Rabbi Israel Yitzhak Kalish of Warka, one of the nineteenth-century’s greatest Hasidic rabbis. The man was crying.

“Rebbe, I’m so desperate, really desperate. My child is sick, I think he is dying. Rebbe, I’m begging you, please pray for my son to recover from his illness.”

The Rebbe sat very still. He closed his eyes and swayed back and forth for a while as he prayed silently,

After a few minutes he opened his eyes, and said very softly, “I’m so sorry to tell you, but I’m not getting the vibe, my prayers are going nowhere. It seems the Gates of Heaven are closed and there’s absolutely nothing I can do to open them. I don’t know what else to tell you. I will keep trying – but it is not looking good.”

The man buried his head in his hands and began to sob uncontrollably. But what could he do?

After he had been traveling for about half an hour he suddenly heard the sound of a horse-drawn carriage chasing after him. He turned around. It was the Rebbe himself, in a carriage drawn by four fast horses.

The Rebbe pulled up beside the man — “Stop your wagon here, stop right now,” he said, “I have something important to tell you.”

The Rebbe helped the man down from his wagon, and they sat together on the grass by the side of the road.

“After you left,” the Rebbe said, “I couldn’t stop thinking about you and your son. You were so, so sad, and your sobbing was so powerful — it broke my heart. After a few minutes, I realized — although I may not be able to help your son, at least I can cry with you.”

And the Rebbe put his arm around the bewildered man’s shoulders, bowed his holy head, and began to sob from the bottom of his heart. He rocked from side to side, tears streaming down his face, as he wailed and sighed.

The man was utterly shocked. He had never seen the Rebbe like this before. Even he hadn’t cried quite so hard. And soon he was also crying, and they were both crying together. They sat there crying, holding each other for comfort, the Rebbe and the man, for a very long time.

All

The man turned to the Rebbe — “What is it?”

The R

That’s the story, and it really is such a beautiful story, but now I want to explain why I think it’s true.

The Torah portion of Haazinu contains an array of fascinating poetic phrases full of the deepest meaning. Many of the couplets in Haazinu teach us remarkable things about God – explaining how we should understand Him and how we should relate to Him.

I would like to focus on one particular verse in Haazinu (Deut. 32:4): הַצּוּר תָּמִים פָּעֳלוֹ כִּי כָל דְרָכָיו מִשְפָט קֵל אֱמוּנָה וְאֵין עָוֶל צַדִיק וְיָשָר הוּא – “The Rock, His work is perfect, all His ways are just; a God of faith, without fault, He is righteous and fair.”

While we all completely buy-in to what this verse is telling us, how are we meant to understand it on a personal level? In other words, how can we introduce this concept into our lives in a meaningful way? After all, in order for anything to have true meaning, however profound it may sound, we must be able to give it a practical application.

The Talmud in Taanit discusses what one should do in the event of a drought. Apropos this discussion, the Jerusalem Talmud (Ta’anit 3:11) relates a story that took place shortly after the destruction of the Second Temple.

There was a terrible drought in Eretz Yisrael and people were starving. The leading sage of the era, Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai, wanted to resolve the matter, so he told one of his assistants to get everyone into the main synagogue, and to tell them to pray as follows: “Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai wants to go and get himself a haircut, but he can’t at the moment because there’s no water.”

And that is exactly what they did. Almost immediately there was a rainstorm — and the drought was over.

This story seems more than a little odd. There were probably thousands upon thousands of people impacted by that drought in all kinds of terrible ways. There was no irrigation for the crops, there was limited drinking water, and limited water for washing as well as for everything else. And we can be absolutely certain that everyone affected was already praying for rain, with all their heart and soul.

And yet, all of those prayers had apparently made no impact on God. The rain had still not fallen, and there was still no water. The only thing that made an impact on God, if we are to understand the story, was the fact that Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai was unable to get a haircut as a result of the drought.

How are we to make any sense of this narrative? Why should Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai’s haircut matter more than the dreadful and real suffering of so many thousands of others? What is the Talmud telling us by informing us that the rain only fell after this curious complaint? And why was it important to get everyone else to pray for his haircut? Why couldn’t he just pray for it himself?

Rabbi Elchonon Wasserman, the saintly head of the yeshiva at Baranovich who was martyred by the Nazis, explained that this is exactly what our verse in Haazinu means. God’s justice is utterly precise. For whatever reason, the population that suffered during the drought had not managed to change the decree and lift the drought, and Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai instinctively understood that this was not an injustice. Even he had been affected by the drought, just like the rest of the people, as he also had a limited supply of water for his basic needs.

However, Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai felt that not being able to get a haircut was a step too far – perhaps he couldn’t study if his hair was too long, or perhaps he thought that it was inappropriate for a senior rabbi like him to look undignified with wild hair. Or possibly the barber needed his livelihood more than

We will never know the exact details, but whatever it was, Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai felt that he needed God to know that it wasn’t fair. And even if from our perspective Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai’s pain seems trivial, the Talmud wants to convey the message that it is

But even more importantly, there is another message here. We all tend to look at ourselves as part of a group when it comes to group things, and as individuals when it comes to individual things. But it is all connected. Our personal pain is not just about us.

We are often drawn to prayer to ask for the needs of others, but we don’t think to introduce our own pain into the prayer. Evidently, we are not suffering when others are in pain, viewing it as second-hand pain instead of a first-hand pain that hurts us. What we need to do is to insert our own personal pain into all our prayers for others.

Maybe that is the magic wand which was the gamechanger for Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai — getting others to pray for his haircut — and maybe this is the magic wand which can be the gamechanger for us too.

God decides that someone should be sick – perhaps that was their destiny. We can pray all we want, but it won’t change anything. However, their pain destiny was not our pain destiny, so if we are in pain with them, God might just think again.

And I think this is the key to understanding Rabbi Carlebach’s story. I believe that when Rabbi Israel Yitzhak of Warka first prayed for the man’s dying child, he was praying for someone else’s pain, and for that reason his prayer was ineffective. It was only when he started crying with his own pain that the G

Which is why, as it turns out, at least this Reb Shlomo story must be true.

Images – Top: Rabbi Dunner together with the late Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach in London, 1987. Bottom: the last resting place of the Hasidic master Rabbi Yisrael Yitzhak Kalish of Warka, in Warka, Poland.