THE HUMILITY OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN

The Book of Leviticus begins with the word “

The medieval commentator, Rabbi Jacob ben Asher, explains the reason behind the mini-aleph. Although Moshe was a great man, he was also extremely humble, an attribute that is best illustrated in the exchange between Moses and God regarding the word “Vayikra”.

Moses only wanted to write “

vayikar ”, which implies chance, as if God only appeared to him in a dream, just like [he appeared to the gentile prophet] Balaam. But God told him to write the word with an aleph [which implies that God appeared to him deliberately]. Moses, in his humility, responded that he would only write an aleph if he could write it smaller than all the other alephs in the Torah, and that is what he did.

Truthfully, this whole humility idea seems rather ridiculous. True, we are told that there was no humbler man than Moses on the face of the earth (Num. 12:3), and yet the image of him as humble hardly matches up with what we know about him.

Moses was raised in Pharaoh’s palace by a royal princess, not quite humble beginnings. In the first recorded story of his adult life, he stumbles onto an Egyptian beating up a Jew — and immediately kills the Egyptian to save the Jew. But while what he did to save the Jew was certainly brave and praiseworthy, it can hardly be considered as humble – killing someone is not the kind of behavior we associate with a humble man.

Later, God calls on Moses to save the Jews and redeem them from slavery. Moses’ response? A flat-out ‘no’. What kind of person refuses a direct request from God? Certainly not a humble one.

Upon discovering that the Jews had created and worshipped a golden calf, Moses broke the Tablets given to him by God, and although we know God subsequently praised him for this impulsive act, surely it was incredibly arrogant for him to break them in the first place? After all, who was he? A mere human being. How was it possible for him to take God’s gift and smash it? How could we ever consider this the act of a humble man?

In that same

And this just precipitates the biggest question of all. Let’s face it – who was the person who wrote the Torah down for posterity? Moses. And how many times is his name mentioned in the Torah? Not once, not 10 times, not 100 times – Moses name is mentioned in the Torah no less than 616 times, multiple more times than anyone else’s name. Forget the mini-aleph — if Moses was actually so humble, why does his name appear in the Torah so many times?

Some weeks ago, I received a gift from my friend Ben Shapell — his book Lincoln and the Jews, co-authored by him with another dear friend, Professor Jonathan D. Sarna. Lincoln and the Jews is a fascinating book about President Abraham Lincoln – a man who shaped the destiny of the United States at a crossroads moment – and his relationship with the American Jewish community of his day.

Interestingly, although Lincoln is consistently rated as the best president in US history, during his tenure at the helm of the executive branch he was hated and reviled. And yet, even though his enemies found fault in almost everything he did for the country, they still admired him.

Edward Dicey was a British journalist with a reputation as a fierce Lincoln critic. During his extended visit to the United States in 1862 he was introduced to Lincoln at a social event and later said:

In my life I have seen a good number of men distinguished by their talents or their station, but I never saw anyone, so apparently unconscious that this distinction conferred upon him any superiority, as Abraham Lincoln.

But despite this widely held view, the fact that Lincoln was considered modest and unassuming is puzzling, and it has always amazed me. He may have been polite and deferential in social company, but he was also incredibly forthright and opinionated.

In 1863, the New York Tribune challenged Lincoln to come out in favor of the abolition of slavery, now that he was at war with the southern states that supported slavery.

Infuriated, Lincoln fired off a letter to the editor which was completely unequivocal:

[My interest in pursuing this war is to] save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. The sooner the national authority can be restored; the nearer the Union will be “the Union as it was.” If there be those who would not save the Union, unless they could at the same time save slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time destroy slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery.

The letter continued on—relentless, unyielding, and uncompromising. Of

One of the best-known stories regarding Lincoln’s humility concerns his letter to General George Meade, a senior commander of the Union Army during a decisive period of the American Civil War. After the Union victory at the Battle of Gettysburg in June 1863, in which Meade played an important role, instead of pursuing and capturing General Robert. E. Lee and his Confederate army, thereby ending the war, Meade and his colleagues gave Lee and his men the chance to flee across the river, and the war dragged on for almost two more years.

Lincoln was livid and vented to his White House staff—against Meade in particular. The news of Lincoln’s irate response quickly reached Meade and he immediately threatened to resign, defensively dismissing Lincoln’s aspersions regarding his competence.

Upon hearing of Meade’s indignant response, Lincoln sat down and wrote him a harsh letter to explain his irritation at the general’s inexplicable decision to allow Lee the opportunity to get away:

My dear general, I do not believe you appreciate the magnitude of the misfortune involved in Lee’s escape—He was within your easy grasp, and to have closed upon him would, in connection with the our other late successes, have ended the war. As it is, the war will be prolonged indefinitely… Your golden opportunity is gone, and I am distressed immeasurably because of it.

If Meade had thought about resigning before the letter, he would certainly have resigned immediately — and probably gone into exile — after he received it. But Meade never did receive it, because Lincoln never sent it. He waited until the following morning and then decided, on reflection, not to send the letter after all.

Lincoln scholars cite this story, and marvel at Lincoln’s humility, his self-control, and his fantastic character. But when I first heard this story, I could not help thinking to myself – humility? – if Lincoln was that humble, surely he would have taken the letter he had written to Meade and ripped it to shreds. By preserving it in his files and noting that he had never sent it, was he not letting us know how “humble” and “restrained” he was? Where is the humility in that?

But in reality, my question was based on a false understanding of humility. We all imagine humility to mean a complete lack of ego. Nothing is about me and my opinions are not that important. But this is not the definition of humility, it is low self-esteem.

Ego is not evil in-and-of-itself. Only when

When it came to the duties of the presidency, Lincoln was fierce. But when he felt the need to vent his personal frustrations, and to settle a score with a recalcitrant general, Lincoln was humble – indeed, he was the humblest of men. But how would anyone learn that lesson if no one knew that Lincoln had written the letter and then not sent it? Lincoln wished to preserve for future generations this important lesson in humility, and what better way to do that than to file away the contentious letter he had never sent.

Moses was undoubtedly the most humble person who ever lived. But when it came to furthering the greater good he allowed his ego, his self-confidence, his genuine superiority, to act and be heard.

When approached by God to lead the Jews out of Egypt, Moses genuinely felt he was not the right person – surely there were others among the elders who were more up to the task? And so he spoke up, for the greater good.

When he realized the Jews had worshipped a golden calf – Moses genuinely felt that the Tablets were too precious for them, and so he smashed them, for the greater good. And he was absolutely right – as God confirmed.

In fact, each time Moses remonstrated, argued and pleaded with God, using his position and even his name as leverage – it was all for the greater good. But when it came to the word “Vayikra”, Moses thought to himself, what possible good could be served by knowing that he personally communicated with God? In Moses’ view to use the

That was why he said to God – take out the aleph, to which God replied, no – leave it in. In the future, how will anyone know the difference between using one’s ego for the greater good, or letting it turn you into a narcissistic pompous ass?

Only on that

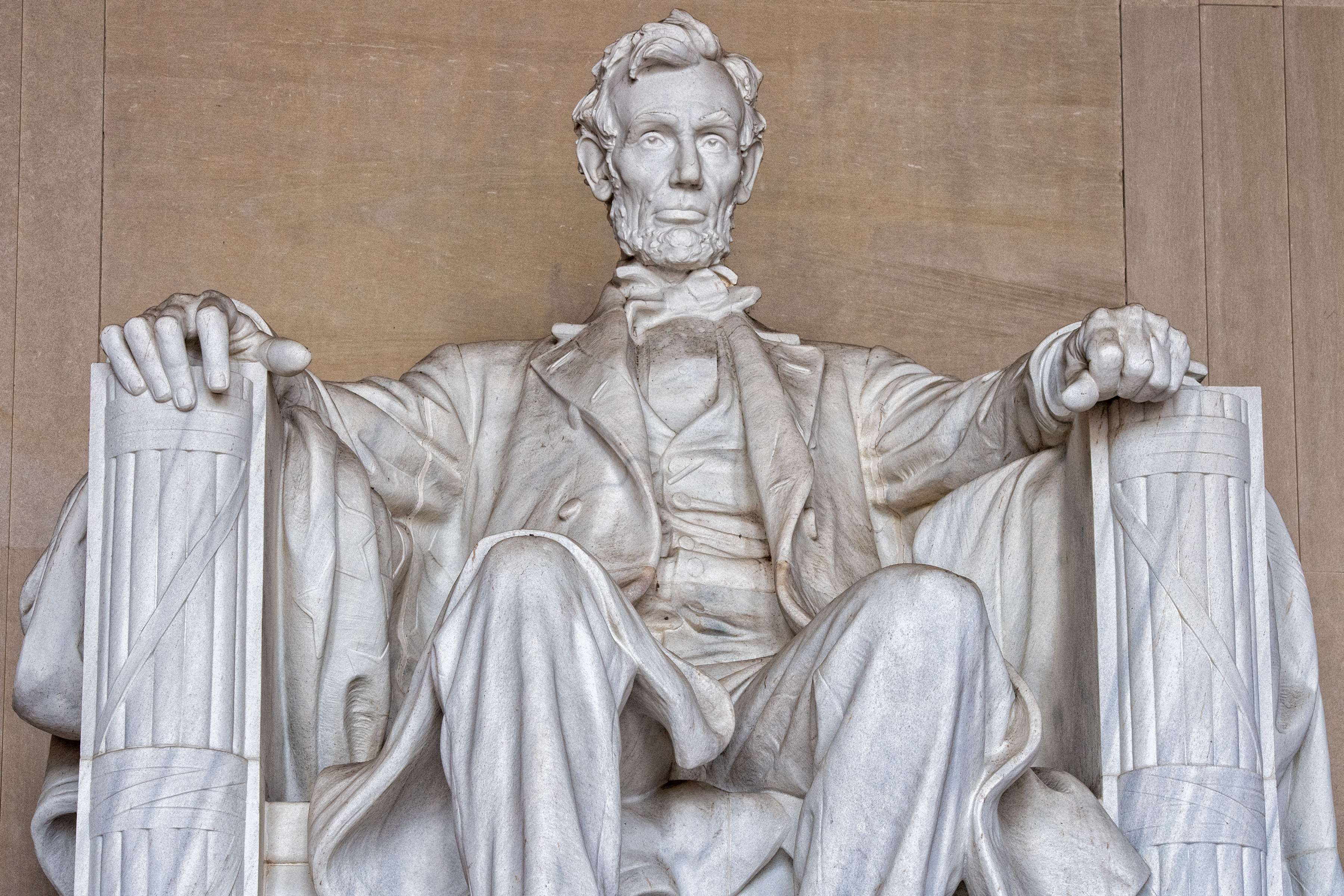

Photo: Abraham Lincoln statue at Washington DC Memorial. Image Copyright: Andrea Izzotti