THE BURDEN OF RESPONSIBILITY

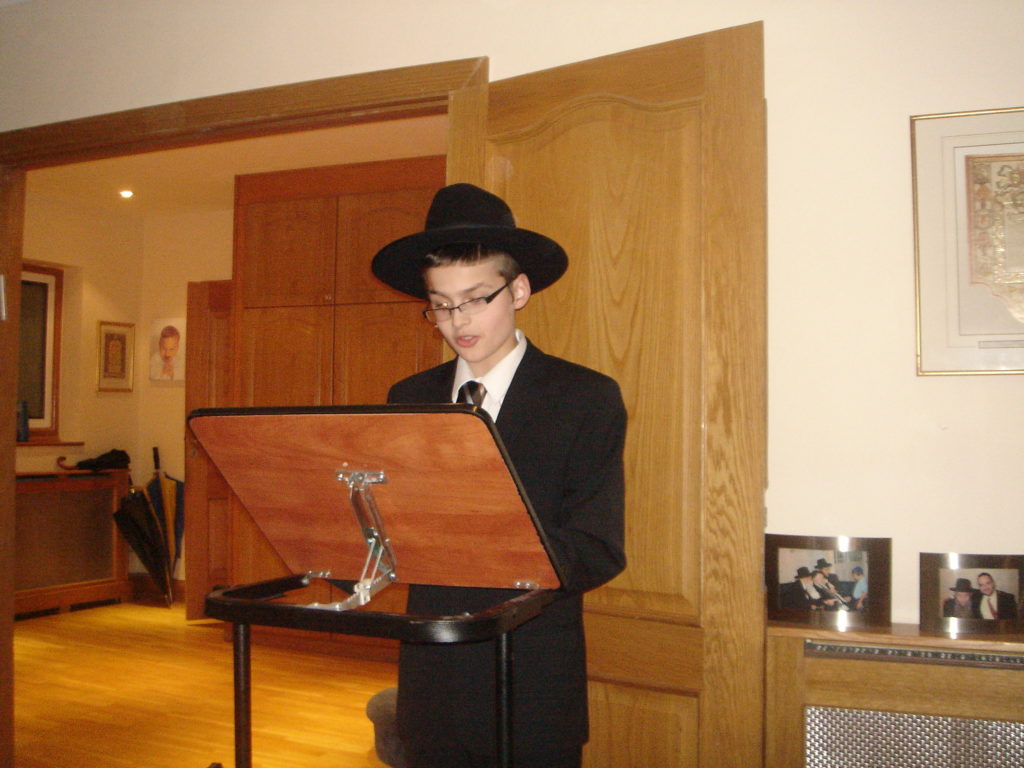

Speech delivered by Shlomo Dunner at his barmitzva in Hendon, London, on January 8, 2010.

At the beginning of Parshat Shemot the Torah tells us: וימת יוסף וכל אחיו וכל הדור ההוא – “Joseph and all his brothers died, and the entire generation.”

In Berachot (55a) Rashi suggests that this verse is proof that Joseph died before all his brothers, as his death is mentioned separately and before that of his brothers.

Rav Baruch Halevi Epstein, in his commentary Torah Temimah, comments that the verse itself is not the proof, but the fact that Joseph’s death had already been mentioned at the end of Vayechi means that there must be a special reason for it to mentioned a second time at the beginning of Shemot, as the verse could have simply said ‘and the children of Jacob died, and the entire generation.” The fact that Joseph is mentioned separately and before his brothers must be to make the specific point that he had died before they did.

The question is: why did Joseph die first, and why at 110 years old, 10 years younger than his brothers all were when they died? The gemara in Berachot in on which Rashi commented says as follows: “Why did Joseph die before his brothers? Because he assumed a role of ‘rabbanut’ (authority).”

Torah Temimah quotes Pirkei D’Rabbi Eliezer (39) which says: “The sons of Jacob uttered the phrase – ‘your servant, our father’ – ten times to Joseph about Jacob, and Jacob heard them say it and kept silent – and silence is the same as agreement. As a consequence, his life was cut short by ten years.”

The Torah Temimah points out that the phrase is only mentioned five times in the Torah narrative, but Joseph was punished for ten, as he heard it twice each time they said the phrase – once in the original Hebrew from his brothers, which he of course understood, and then once again in Egyptian when the interpreters translated it.

According to this version of events, the reason Joseph lived a shorter life than his brother and died before they did was because he had not protested when his father was referred to as his servant, which, says the Torah Temimah, was a form of ‘rabbanut’, which Pirkei D’Rabbi Eliezer interprets to mean behaving with misplaced superiority.

The Torah Temimah points out that Pirkei D’Rabbi Eliezer was compelled to put forward this forced understanding of the Gemoro in Berachot because of a Midrash on the verse: ויוסף היה במצרים – ‘And Joseph was in Egypt’ – which immediately precedes וימת יוסף וכל אחיו.

The Midrash learns that this verse teaches us that although Joseph was the ruler of Egypt, he remained Joseph, in other words, he behaved like a son and a brother to his father and brothers, and not like a king with all the airs and graces that generally accompany such a position.

This Midrash prevents Pirkei D’Rabbi Eliezer from suggesting that Joseph assumed an air of authority and superiority over his family, as seems to be the implication of the Gemara in Berachot, says the Torah Temimah, and Pirkei D’Rabbi Eliezer is therefore forced to come up with an aspect of Joseph’s behavior which, in such a great and righteous individual, can be interpreted as a misplaced superiority, and therefore would result in a punishment as severe as a shortened life.

The source for the characteristic of ‘rabbanut’ causing an early death, says the Torah Temimah, is a Gemara in Pesachim (87b): “Woe is to authority (‘rabbanut’) because it buries its holders!”

The Torah Temimah interprets this Gemara to mean that a person who asserts himself over his equals, or worse – over those greater than him, will be punished with an untimely death.

However, this whole understanding of Joseph’s early death is contradicted by another Gemara, this one in Sota (13b). The Gemara there says: “Why was Joseph referred to as ‘bones’ during his lifetime? This is not respectful language to use about the righteous! The answer is because his brothers used the disrespectful phrase ‘your servant, our father’ about his father and he said nothing to them in protest.”

This Gemara there seems to describe an entirely different punishment for Joseph for his having ignored the disrespectful references to his father. Rather than being punished by having his life shortened, he was punished by being referred to disrespectfully as ‘bones’ by the Torah during his lifetime. This punishment is reciprocal, and certainly seems more proportionate to the sin of his silence.

The Torah Temimah says that the reason the other Gemara did not go for this alternative interpretation is most probably because Rabbi Chama, the author of that version, felt that the reference to Joseph as ‘bones’ in the Torah does not fit the criteria of a punishment, as it was he who is quoted as saying ‘take up my bones from Egypt.’ Rabbi Chama, therefore, came up with the alternative punishment of an early death for Joseph for his not having reacted when he heard the disrespectful references to his father.

The Torah Temimah admits that there is a serious problem with this explanation. The Gemoro in Sota that is identical with our original Gemara in Berachot about ‘rabbanut’ being the cause of Joseph’s early death offers two Amoraim as the authors of this homily – one is Rabbi Chama ben Rabbi Chanina – the same as in Berachot – and the other one is Rabbi Yehuda in the name of Rav, the rabbi who offers the alternative homily in Sota!

How is it possible that Rabbi Yehuda agrees with Rabbi Chama about the punishment for having ignored the disrespectful references to his father he offers a completely different interpretation in Sota?

The Torah Temimah suggests that the reading in Sota is wrong and that Rabbi Yehuda’s name should be deleted from the text so that the homily in Sota is identical to the one in Berachot.

However, I would like to suggest an alternative explanation, and indeed an entirely different interpretation for the Gemara in Berachot than the one put forward by the Torah Temima. This interpretation requires no deletion of names from the text of the Talmud.

We have assumed that someone who assumes a role of authority has done something wrong – a sin for which he must be punished, apparently with an early death, hence “woe is to authority (‘rabbanut’), because it buries its holders!”

Perhaps, though, this is not the case at all. Perhaps it is not a sin that results in punishment, but a burden that results in a shortened life. Perhaps the toll of public responsibility leads to an early death, and rather than being a punishment, it is the tragic but inevitable result of the extra stress and worry that the strain of leadership puts on someone, affecting his health and ultimately his lifespan.

There is a Gemara in Sanhedrin (14a) that makes this exact point: “Reb Zeira would hide in order to avoid being ordained, as Reb Eliezer said one should always remain in the dark, in other words in obscurity and free from the burdens of leadership, and then one will live.”

According to Rabbi Chama, the reason Joseph died before his brothers and at a younger age was not because he had sinned, but because as the ruler of Egypt he had assumed a life-sapping public role. In which case, Rabbi Chama and Rabbi Yehuda could be the joint authors of the homily about ‘rabbanut’, and Rabbi Yehuda can still be the author of the homily about ‘bones’.

The only disagreement that remains is between Pirkei D’Rabbi Eliezer and Rabbi Yehuda over the punishment received by Joseph for remaining silent when hearing his father referred to as ‘your servant, our father’ ten times by his brothers.

In any event, according to Pirkei D’Rabbi Eliezer, the ten years reduction in Joseph’s life had nothing to do with ‘rabbanut’, but was simply a reflection of the ten times he heard the phrase ‘your servant, our father’ and remained silent – a ratio of one-year reduction per mention.

May we all merit lengthy lives and to see the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem, speedily in our days, Amen!