REVOLUTIONS HAVE TO COME IN PAIRS

It is in an axiom of the American national narrative that in 1776, citizens of the thirteen colonies of the union declared themselves independent of Great Britain, freeing themselves from the control of the British monarch, George III, and his government of pompous, autocratic aristocrats.

The Revolutionary War that accompanied the formal severance of ties with Great Britain resulted in tens of thousands of deaths, and both sides in the conflict spent huge sums of money to secure victory.

Ultimately, when the dust had finally settled, it was the American patriots who had won the day, partly due to French military support, but principally as a result of the widespread revulsion across the colonies for British arrogance, and the blatant insensitivity to the needs and concerns of the colonists they sought to control.

Although this narrative is the one that is widely embraced, it actually fails to take into account a powerful truth that undercuts it completely, namely the emergence during the 1780’s of a powerful group of legislators, known as the Federalists, who sought to reunite the United States with Great Britain, and to ditch republican democracy in favor of a monarchical system, or at least a system far more similar to the one they had just repulsed than the one represented in the lofty ideals of the Declaration of Independence.

At the head of the Federalist group was Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, who counted John Adams among his many avid supporters, while George Washington — who remained largely aloof from partisan politics — was also broadly sympathetic to the Federalist cause.

Opposition to the Federalists was led by Thomas Jefferson, the brilliant Virginia-born polymath who single-handedly wrote the 1776 Independence Declaration, and who was utterly devoted to the republican cause.

Believing that the future of universal freedom depended on a system which allowed everyone to have a voice, not just a bunch of self-important legislators and rich people, he refused to bow to Federalist pressure, even after the republican-inspired French revolution turned sour and produced the infamous Reign of Terror, casting plausible doubt upon the very new democracy-for-all experiment.

The pivotal moment for America came after the presidential election of 1800, when Jefferson beat Adams, but tied with Aaron Burr, his choice for vice-president.

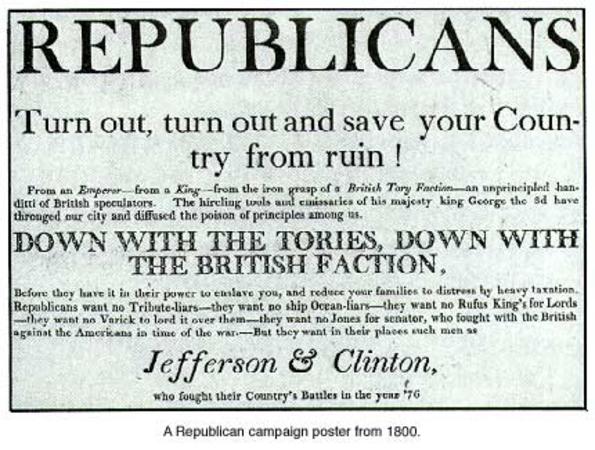

According to the peculiar constitutional rules then in place this meant that either of them could be named president. The Federalists preferred Burr over Jefferson, their avowed enemy, and did everything in their power to ensure that Burr secured the top job. Ultimately, Jefferson prevailed, in what would become known as the “Revolution of 1800”.

What makes this revolution far more remarkable than the one in 1776 was not that Jefferson beat Adams in a bitterly fought election, nor that he unpredictably prevailed against the Federalists and their British patrons. Rather it is the fact that this was the first time in recorded history power passed from one group to another without anyone being killed or imprisoned, despite the great mutual enmity between the parties involved, and the profound disagreements that characterized their ideologies.

There is no doubt that the year 1800 was the year true democracy, and the benefits it offered to ordinary individuals, was born.

This second American Revolution strikes me as an extremely important, if overlooked, historical example of the phenomenon of one momentous transformative event needing to be followed by another in order for the first to be truly consequential.

Our own history as Jews began with exactly with this sequence, with the Exodus from Egypt of a slave nation into freedom, followed seven weeks later by the revelation at Mount Sinai, and the gift of God’s Torah for the nascent Jewish nation.

The first ‘revolution’ only became meaningful once the ex-slaves had internalized their freedom from human oppression and their direct involvement with God, both individually and collectively.

Once identified, this dual-revolution phenomenon is both observable and obvious throughout history. Nevertheless, it seems curious, to say the least. Why are first revolutions never enough to effect a permanent break with the past? Why would American colonists who had suffered under the yoke of British tyranny and misrule ever have contemplated a return to anything remotely connected to British governance? Why would Jews emerging out of a Red Sea that had miraculously split to save their lives, and that had also drowned their oppressors, not immediately be ready to receive the Torah? Why does one need a second epiphany to perpetuate the first?

It is often the case that the ecstatic emotions that accompany a transformation from one reality to another are dampened and overshadowed by the challenges emanating directly from the overwhelming success of that transformation. The elusive pot of gold at the end of the rainbow is not actually as glittering when encountered close-up.

All of a sudden, the fleshpots of Egypt (or of Great Britain!) seem rather more attractive than they did before the celebrated moment of redemption. It is only once this anticlimax has been experienced, and then overcome, that the true revolution can take place, shattering the psychological bonds with the past once-and-for-all. The second revolution is actually the final act of the first.

That is why we count the days between the first day of Passover and Shavuot, the festival that commemorates receiving the Torah.

That is why this period of “sefirat ha’omer” is considered similar to the intermediate days of the Passover and Sukkot festivals, as we recall in real time the period that separated the first revolution and the second.

And, possibly, that is one of the reasons why this period in our calendar is not a happy one, as we struggle to find our feet in our newfound freedom and liberty.

Although, as long as we stay focused on the consummation of the initial redemption through the Mount Sinai revelation, we can be sure to shake off the shackles of Egyptian slavery, so that our Pesach freedom brings us into God’s Shavuot embrace.

Photo: Republican campain poster, 1800 election. Public Domain.