REBEL RABBI OF LONDON – THE EPIC BATTLE AGAINST JOSEPH SHAPOTSHNICK

Dedicated to the memory of Rabbi Eitam Henkin (1984-2015)

This article is the product of many years of research into the quite bizarre and extremely controversial character, Joseph Shapotshnick of London. It was as a direct result of my research into Shapotshnick and his shenanigans that I first came across the eminent rabbinic leader Rabbi Shmuel Yitzchak Hillman. As is always the case with historical research – you start off in one place and you end up in another. Shapotshnick led me to Rabbi Hillman, and then, as I delved deeper into Rabbi Hillman’s writings and the circumstances of his life, I became more and more intrigued by his character and his manifold achievements.

A couple of years ago I shared some of my research into Rabbi Hillman with his great-grandson, my good friend Isaac (Bougie) Herzog, then Chairman of the Jewish Agency, now President of Israel. Following our discussions, we decided to jointly republish Rabbi Hillman’s דרושים לכל פרשיות של ספר בראשית (“Homilies for all the Portions in the Book of Genesis”), one of the more than 20 books he published under the title Ohr Hayashar. Last Spring, we republished the book (Yad Harav Herzog, Jerusalem, 5780/2020), in a revised, corrected and annotated edition, along with the first full monograph biography of the illustrious author.

During the time it took to prepare the book for republication, I decided to write an accompanying article about a little-known chapter in Rabbi Hillman’s rabbinical career – namely, the transglobal protest campaign he led from behind the scenes against an obscure rabbinic figure in London called Joseph Shapotshnick, in the wake of the latter’s attempt to offer radical solutions for the vexed problem of agunot. While waging this extraordinary campaign, Rabbi Hillman succeeded in recruiting the majority of the international rabbinical establishment to come out publicly against his interlocutor. This article and the dramatic story it recalls adds yet another layer to the amazing life and career of Rabbi Hillman, as presented in the biographical chapters at the end of the new edition of Ohr Hayashar.

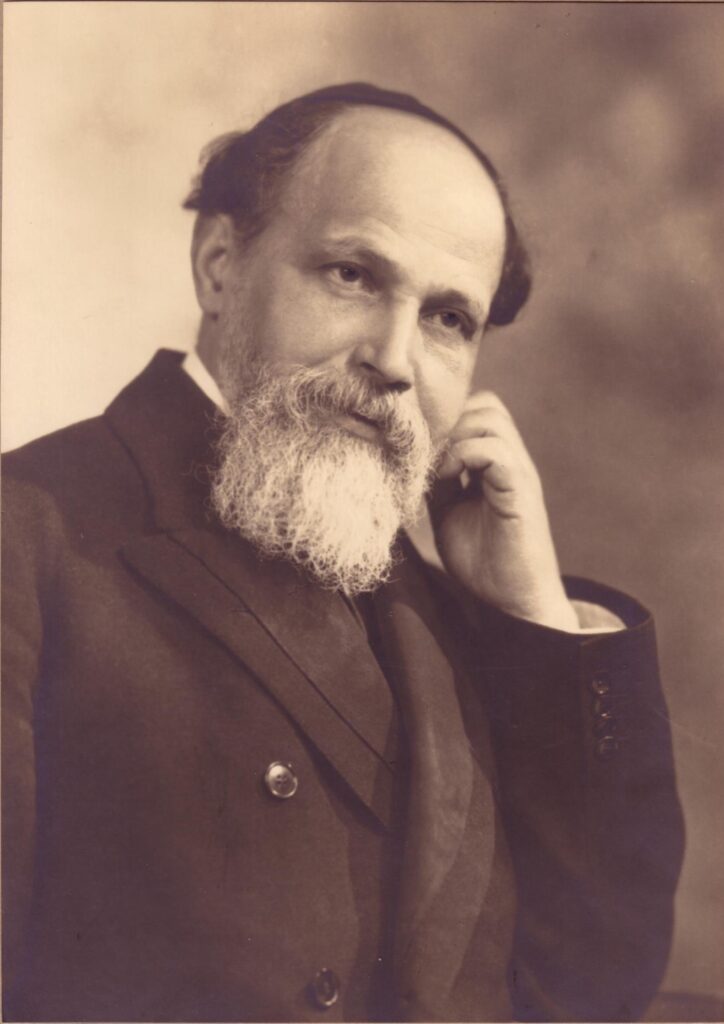

THE TRAGIC DEATH OF RABBI ELIEZER GORDON OF TELZ

“In the days of [the Chief Rabbi of Great Britain] Dr. [Hermann] Adler, rabbis were not allowed to be referred to with the title ‘rabbi’ … they could only be called ‘reverend’ or ‘minister’. And when [Rabbi Adler] wrote to them, he called them ‘minister.’[1] Possibly as a result of the rabbinical conference in Leeds in 5671 (1911), in which [Rabbi Adler] was publicly exposed as a hater of [traditional] rabbis and as a destroyer of Judaism, he softened a little, and his power diminished, and eventually he died. Before he died, his only son [Shlomo also] died – [he was the son] who would have taken his [father’s] place. [That year] his wife also died. And everyone said it was because he had humiliated the great Torah scholar, the tzaddik, foundation of the world, Rabbi Eliezer Gordon of Telz.”[2]

“[In the year 5670/1910] Rabbi Gordon came to London to solicit help to construct a new building for his yeshiva, and [Rabbi] Dr. Adler spoke to him as if he was speaking to a low-class person, and was annoyed at him for coming to visit his private residence, rather than coming to see him at the Beit Din like any other member of the public. As a result [of this mistreatment] he distressed [Rabbi Gordon], who had a weak constitution, and after a day or two [Rabbi Gordon] suddenly died. All the people cried out in mourning, as if the “Ark of God” had been taken [from them] … They built him a large mausoleum and tombstone at his gravesite, and in mourning his death honored him more than any rabbi [who had died in England] until that point in time. May his merit protect us and all of Israel, for he was a prince of Torah, a pillar of reverence, possessed of a great and splendid mind, with clear, sharp, powerful insight – [a great] rabbi of Israel.”

These two quotations are excerpted from the unpublished memoirs of an important rabbinic leader from London called Rabbi Tzvi Hirsch Ferber (1879-1966). Rabbi Ferber, a great Torah scholar, was born in Slabodka, Lithuania, and was a gifted orator, a prolific writer, and one of the early founders of the Haredi community in England, where he arrived shortly after the passing of Rabbi Gordon. Initially Rabbi Ferber spent a brief stint in Manchester, where he founded a yeshiva. Then, in 1913, he was appointed rabbi of the Chesed v’Emet congregation – a small community of working-class Jewish immigrants located in the Soho district of West London – where he remained until the end of his life.[3]

Rabbi Tzvi Hirsch Ferber

In this extract from his memoirs, Rabbi Ferber brings to light a particularly notorious episode in the modern history of British Jewry – an episode that is especially important with reference to the rabbinical career of Rabbi Shmuel Yitzchak Hillman.

At the beginning of 1910, Rabbi Eliezer Gordon, Rosh Yeshiva and rabbi of the city of Telz (Telšiai) in Lithuania, traveled to England to solicit donations to pay for the construction of a new building for his yeshiva, after the previous building had completely burned down. On Friday, February 11, 1910, he met with the official Chief Rabbi of Great Britain, Rabbi Dr. Hermann (Naftali) Adler (1839-1911). For unexplained reasons, Rabbi Adler treated the visiting dignitary with indifference and even disdain, despite the fact that he was among the foremost rabbis of that era. To make things worse, Rabbi Adler also categorically refused to help with Rabbi Gordon’s fundraising campaign.

The Telz Rosh Yeshiva was crestfallen by the encounter, and the following day, on Motzei Shabbat, 4 Adar I 5670 (1910), he suddenly keeled over, and within hours he was dead. His sudden and tragic death shocked the local immigrant Jewish community in the “East End” district of London, and rightly or wrongly they pointed the finger of blame at the Chief Rabbi. The funeral was mobbed – London Jewry turned out in their tens of thousands, first in the East End, and later to witness his burial at the Edmonton Jewish Cemetery in North London.

The next day, newspapers reported that over fifty thousand mourners had attended the funeral, and that it was the largest Jewish funeral ever held in England.[4]

A long list of distinguished rabbis attended the funeral, quite remarkably including Chief Rabbi Adler, who was astonished by what he saw. Stunned by the huge crowds, he asked one of his colleagues what the fuss was about. The other rabbi wryly replied: “Since the Jewish community of Great Britain was restored under Oliver Cromwell, we have not merited to have such a great rabbi buried in our country.” That insult must have hit Chief Rabbi Adler particularly hard; his father, the illustrious Rabbi Nathan Marcus Adler (1803-1890), who had been the British Chief Rabbi before his demise in 1890 had seen the title pass to his son, had died and been buried in England.

The most impressive eulogy at Rabbi Gordon’s funeral was given by the then relatively unknown Rabbi Shmuel Yitzchak Hillman, at the time a nondescript pulpit rabbi in Glasgow, Scotland. Rabbi Hillman and the late Rabbi Gordon were well-acquainted and had engaged in regular correspondence over many years, and Rabbi Hillman had originally planned to be in London to assist Rabbi Gordon with his fundraising efforts; now, instead, he was there to deliver his friend’s eulogy.

Rabbi Hillman was an exceptional orator, and on that cold February day he enthralled the mourners with his fiery words:

Let us imagine for a moment that before the final dirt has been shoveled on top of him, the departed could speak to us himself from his grave, and that we could hear his voice from the depths – surely we would hear from him what Yosef Hatzaddik said of himself when he was in the dungeon during his exile: ‘I have been stolen away from the land of the Hebrews,’ [in other words,] ‘I stole myself away from Russia where so many Jews live,’ – ‘And here, too, I have done nothing,’ – [meaning] ‘I was unable to do ‘any’-thing yet for the sake of the Torah for which I risked my life.’ ‘Rather, they put me in the pit,’ – ‘instead, here they laid me into the grave.’[5]

My dear colleagues and rabbis, if the death of this great scholar in our city has had any effect on our hearts, we must give charitable donations [for his yeshiva]. ‘Whether [we are] a person who gives large amounts or a person who gives small amounts’ [it is our duty] to raise up his holy yeshiva on its foundation, so that, by our enthusiastic response, he will have a share [in rescuing Telz yeshiva from ruin] even after his death – his departure having resulted in the restoration of his yeshiva so that it does not collapse.[6]

When Rabbi Hillman finished speaking, there was not a dry eye in the audience. His dramatic presentation of the final moments of this great scholar who had come to England from Russia to be so coldly treated by the establishment, after which he quickly died and was buried so far from home as a result, made waves at the funeral and was widely cited across the community. In a matter of days enough money was raised not only to rebuild the Telz yeshiva, but also to financially support Rabbi Gordon’s bereft family. One notable significant donor was Lord Rothschild,[7] a meeting with whom the late Rosh Yeshiva had vainly sought via Rabbi Adler when he went to see him that fateful Friday before he died.[8]

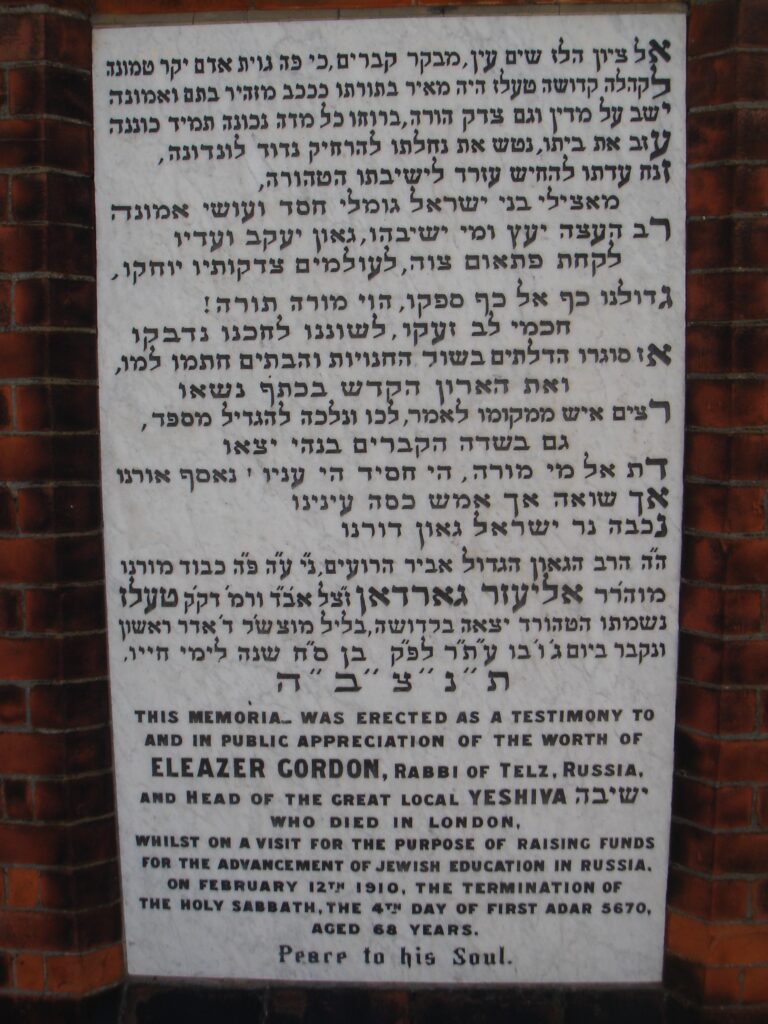

Inscription at the grave of Rabbi Eliezer Gordon of Telz

Significantly, another outcome of Rabbi Hillman’s outstanding eulogy was that it succeeded in bringing him to the attention of London’s Jewish community leaders, who immediately began to think of how they could recruit this powerhouse rabbi to London from his small community in Scotland. As it turned out, they would not have to wait too long.

A NEW CHIEF RABBI COMES TO ENGLAND

A few months after Rabbi Gordon’s unexpected death, on 15 Tammuz 5641 (1911), Chief Rabbi Adler died, and the search for his replacement began. Two years went by before the search was over; a majority vote selected the charismatic Rabbi Dr. Joseph Herman Hertz of New York to replace Rabbi Adler. Rabbi Hertz was not actually American; he was born in the town of Rebrény, then in Austro-Hungary, now in the Slovak Republic, in 1872. In 1884, at age 12, his family immigrated to New York, where the young Joseph attended New York City College and Columbia University.

Rabbi Hertz also studied rabbinics and was ordained by the Jewish Theological Seminary – although it should be noted that this was during JTS’s original incarnation, when the seminary was still nominally categorized as an Orthodox institution, in the period before the presidency of Dr Solomon Schechter. In fact, Rabbi Hertz was the seminary’s very first ordained rabbi. He had also studied privately with various rabbis in New York, who apparently also granted him rabbinical certification, although details of these rabbis are not part of any official historical records.

Rabbi Hertz’s first pulpit was in Syracuse, New York. Then, in 1898, he left the United States to become the rabbi of a community in Johannesburg, South Africa, where he served for over a decade. While he was there, he also lectured in philosophy at Transvaal University. His work promoting equal rights for Jews and Catholics in the South African Republic (then known as the “Transvaal Republic”) and his allegiance to the British during the Second Boer War, earned him the disfavor of the South African government, and there were several unsuccessful attempts to deport him.[9]

In 1911, Rabbi Hertz returned to New York to serve as rabbi of the Orach Chaim congregation on Manhattan’s Upper East Side,[10] and it was after two further years as a rabbi in the United States that he was appointed Chief Rabbi of the British Empire.

But despite being a great Jewish educator and a talented organizer, Rabbi Hertz was by no means a rabbinic scholar as his predecessors had been; he was unfamiliar with managing a Beit Din, nor could he answer complicated halakhic questions.[11] Remarkably, although Rabbi Hertz was not known for his modesty or self-effacement, he must nonetheless have been conscious of this lacuna in his training and expertise, and also acutely aware of the fact that he would need a skilled dayan to stand alongside him and take charge of halakhic matters – especially everything pertaining to personal status, namely divorces, marriages, and conversions. Whoever this person was, he would need to be of such significant stature in terms of his Torah knowledge that he would be accepted without question by both the local Orthodox community in England, most of whom were Eastern European immigrants from very traditional backgrounds, as well as by the senior rabbis of communities in Europe, who would need to know that the rulings issued by the London Beit Din were reliable and trustworthy.

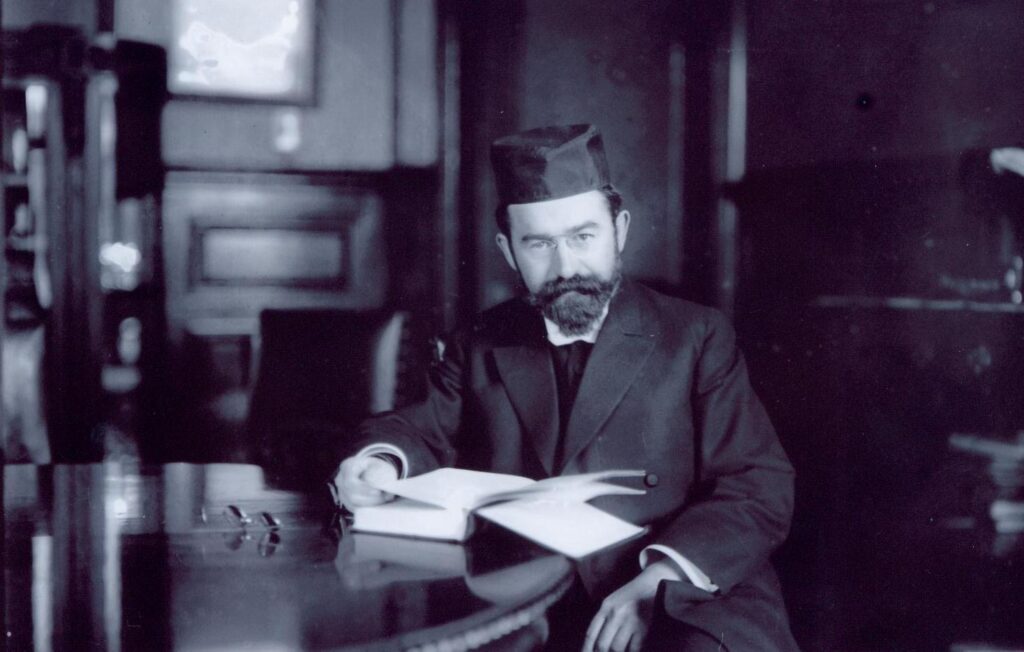

British Chief Rabbi, Joseph Hermann Hertz

After some discussion, the newly-appointed Chief Rabbi and British community leaders decided to offer this important position to Rabbi Shmuel Yitzchak Hillman.[12] The leadership clearly recalled the strong impression Rabbi Hillman’s eulogy for Rabbi Gordon of Telz had made on the community, in addition to which he was reputed for his stellar reputation as an exceptional rabbinic scholar, without doubt one of the finest in the United Kingdom.

Rabbi Hillman was duly approached by representatives of Rabbi Hertz and the community leadership and offered the position. In presenting him with the job description, they explained that although all rabbinical matters would officially remain under the auspices of the Chief Rabbi, in reality, if he accepted the job, he would be in charge of everything relating to halakha.

Rabbi Hillman carefully considered the offer and after some reflection responded that he was willing to accept the position – but only on two conditions. During Rabbi Adler’s time as Chief Rabbi, salaries for the dayanim were personally paid by the Chief Rabbi, and this created the dynamic of “employer and employee” between the Chief Rabbi and his dayanim. Rabbi Hillman felt that halakhic decision-making had to be free of external influences and potential conflicts of interest, including any kind of dependence, financial or otherwise, on a single individual, namely the Chief Rabbi – and so he insisted that his salary had to be paid directly by the official community body, not the Chief Rabbi.

His second demand was that he, and he alone, had to be considered the halakhic ‘last-word’ for any issue of Jewish law involving the community. Rabbi Hillman was worried that as soon as he was appointed a community official, members of the hierarchy and other less scrupulous rabbis would use his reputation to provide themselves with the cover to do whatever they wanted in terms of egregious leniencies in all areas of Jewish law. To avoid such a situation from unfolding, he insisted on a formal assurance that he would always have the last word in halakhic matters, and that no one could ever overrule him.

Rabbi Shmuel Yitzchak Hillman

In short order, the community’s leaders and Rabbi Hertz agreed to Rabbi Hillman’s terms, and in 1914 Rabbi Hillman was appointed to head London’s Beit Din – or ‘Court of the Chief Rabbi’ as it became known – and he presided in that position as one of the most prominent rabbinical figures of the British Empire and well beyond it for the next twenty years.

CRITICS OF RABBI HILLMAN

Rabbi Hillman preferred to remain behind the scenes, and was loathe to waste time on anything that involved public displays of power or honor. Instead, he quietly took charge of rabbinical training and running the Beit Din. Meanwhile, his powerful personality and his profound knowledge of halakhic sources facilitated his widespread acceptance by the community-at-large and by the majority of his rabbinical colleagues as the senior rabbinic authority in London. Rabbi Hillman soon earned the reputation as the kind of rabbi who would always do what was best and right for the community, while at the same time ensuring that standards were kept high and every detail carefully watched.

But no person in a position of power is ever loved by everyone, and some elements within the immigrant community were not impressed by Rabbi Hillman, maintaining that he was too lenient in certain areas of halakha in order to include as many people as possible within the established Orthodox community, despite the fact that in their personal day-to-day lives these people were not really Orthodox at all.

One incessant critic was a brilliant rabbinic scholar, an odd fellow by the name of Shmarya Menashe HaKohen Adler, a Polish immigrant well-versed in Talmud and halakhic literature. An avowed polemicist, Adler published a number of works with the title Mar’eh Kohen which attacked Rabbi Hillman’s rulings and also impugned his integrity and character, and while Rabbi Hillman’s actions were undoubtedly beyond reproach, they clearly were never going to satisfy his impassioned opponent, who denigrated him and his Beit Din mercilessly.[13]

Menashe Adler

To Rabbi Hillman’s great credit, he was not thin-skinned and rarely reacted when people tried to offend or insult him. His only response was to focus even more on what he was doing, and to redouble his efforts strengthening the observance of halakha within his community and beyond.

But while the criticisms of Adler and other similar detractors could be easily ignored as insignificant, one particular person who became fixated on Rabbi Hillman and did everything he could to undermine his authority did engender a vigorous response from his target – a response that would reverberate across the Jewish world, and whose effect is felt to this day. That person was Joseph Shapotshnick, an unusual rabbinical figure whose mercurial career was marked by controversy and notoriety in equal measure.

Although at the time the controversy erupted Shapotshnick lived in London, he was born in Kishinev, Bessarabia (today Moldova), where, according to him, his father had been a leading rabbinic figure known as the “Belzitzer Rebbe.”[14] His father died when he was only 14 years old, forcing his widowed mother to move with her teenage son to Odessa, where they both resided with Pesach Shapotshnick, a man of means who was Joseph’s half-brother from his father’s first marriage.

RABBI AVRAHAM YOEL ABELSON OF ODESSA

Joseph Shapotshnick was a precocious young lad, a bright and talented Torah student with an attractive personality. Not surprisingly, he soon came to the attention of the leading dayan of Odessa, Rabbi Avraham Yoel Abelson (1841-1903), who became very fond of his new protégé and studied privately with him, eventually granting him ordination to rule on halakhic matters.[15] Shapotshnick also made sure to complete a course of study at the local secondary school, and it would appear he was thorough in his studies, accomplishing impressive achievements.

Although Rabbi Abelson is no longer remembered today, during his lifetime he was a well-known Torah scholar of Lithuanian extraction, a close friend of all the major rabbis of the era, including Rabbi Yitzchak Elchanan Spector (1817 – 1896), rabbi of Kovno; Rabbi Naftali Tzvi Yehuda Berlin (1816 – 1893), head of the famed Volozhin Yeshiva and rabbi of Volozhin; and Rabbi Yosef Dov-Ber Soloveitchik (1820 – 1892), rabbi of Brest-Litovsk (Brisk). Complicated halakhic questions were posed to Rabbi Abelson from all over Europe, and he gained a reputation as a brilliant halakhist, unafraid of the criticism he might attract from more cautious or more conservative rabbis when he ruled leniently.

Odessa was a cosmopolitan city with an assimilated Jewish community, and Rabbi Abelson knew how to be flexible, cleverly navigating the outer edges of halakha and the limits of inclusion. One particularly notorious and controversial case that he had to contend with concerned a woman called Sarah Genner, whose husband died after several years of marriage without them having had any children. Sarah Genner’s husband was survived by two brothers, but both of them refused to take part in the halitza ritual that would allow Sarah to remarry, as they were both apostates – Jews who had converted to Christianity – and their priest had ruled that they were forbidden to take part in a ritual of another religion, namely Judaism.

Relying on the opinion of earlier rabbinic scholars, according to whom someone who converts to another religion is no longer considered a part of the Jewish people,[16] and for various other reasons, Rabbi Abelson ruled that Sarah Genner could get married to a new husband without halitza. This lenient ruling caused a significant stir in both the rabbinic world and in the international Jewish press, as a result of which Rabbi Abelson was compelled to defend himself in writing and in various public addresses. His network of distinguished rabbinic friends, including those already mentioned, were unceremoniously dragged into the affair, after Rabbi Abelson’s detractors went out of their way to “report” his actions to them.[17]

This episode and Rabbi Abelson’s steadfastness clearly left a strong impression on his young protégé Joseph Shapotshnick; the robust sense of independence, the willingness to be decisive about a situation involving serious dispute; not to back down or cower when attacked by one’s opponents; the publication of polemical texts; and complete confidence in one’s own knowledge – these ideals and tactics would all later feature in Shapotshnick’s own experiences when faced with opposition to his attempts to offer dispensations permitting agunot to remarry without halitza.

SHAPOTSHNICK ARRIVES IN LONDON

Shapotshnick emigrated to London in 1913 and spent the rest of his life there.[18] There is no doubt that he was both very talented and extremely charismatic, but it is also true to say that he expended a great deal of time and money on overly ambitious ideas that never came to fruition, and on publishing projects that tailed off before they could be completed.

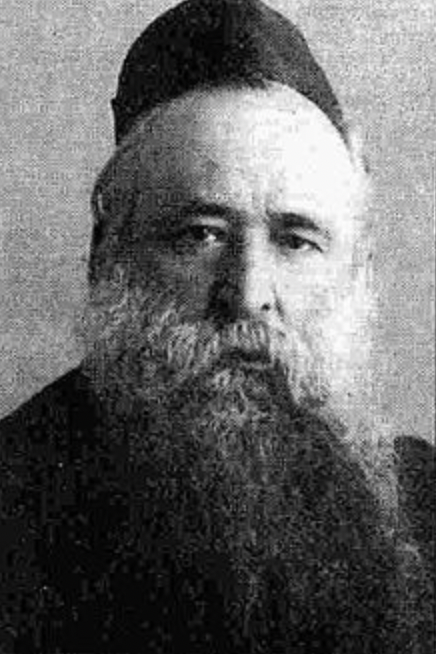

A self-issued PR photo of R. Joseph Shapotshnick

During the course of his active adult years, Shapotshnick published countless books, journals, newspaper articles, tracts, and pamphlets, often in collaboration with other rabbis and writers. His most notable work was the Shas Hagadol Shebigedolim (“The Largest of the Large Talmuds”), published in 1919, which in its physical size has the curious distinction of being the largest religious Jewish book ever produced. According to Shapotshnick, in his role as the shamelessly self-promoting editor-in-chief, Shas Hagadol Shebigedolim augmented and enhanced the text of the Talmud by incorporating the work of over one thousand commentaries, as well as a commentary of Shapotshnick’s own composition.

The idea behind this ambitious project was to facilitate the study of Talmud by those who had not spent years studying in yeshiva, and there is no question that for its time this was a groundbreaking concept, pre-empting the Steinsaltz edition of the Talmud and the ArtScroll Shass by well over half a century. But like most of Shapotshnick’s plans, despite the fact that the idea behind it was bold and impressive, the project’s execution was deficient and haphazard. Notwithstanding his promise to print the entire Talmud using the Shas Hagadol Shebigedolim format (Shapotshnick estimated the final result would amount to no less than three million pages!), only the first volume, on Tractate Berakhot, was ever actually published.

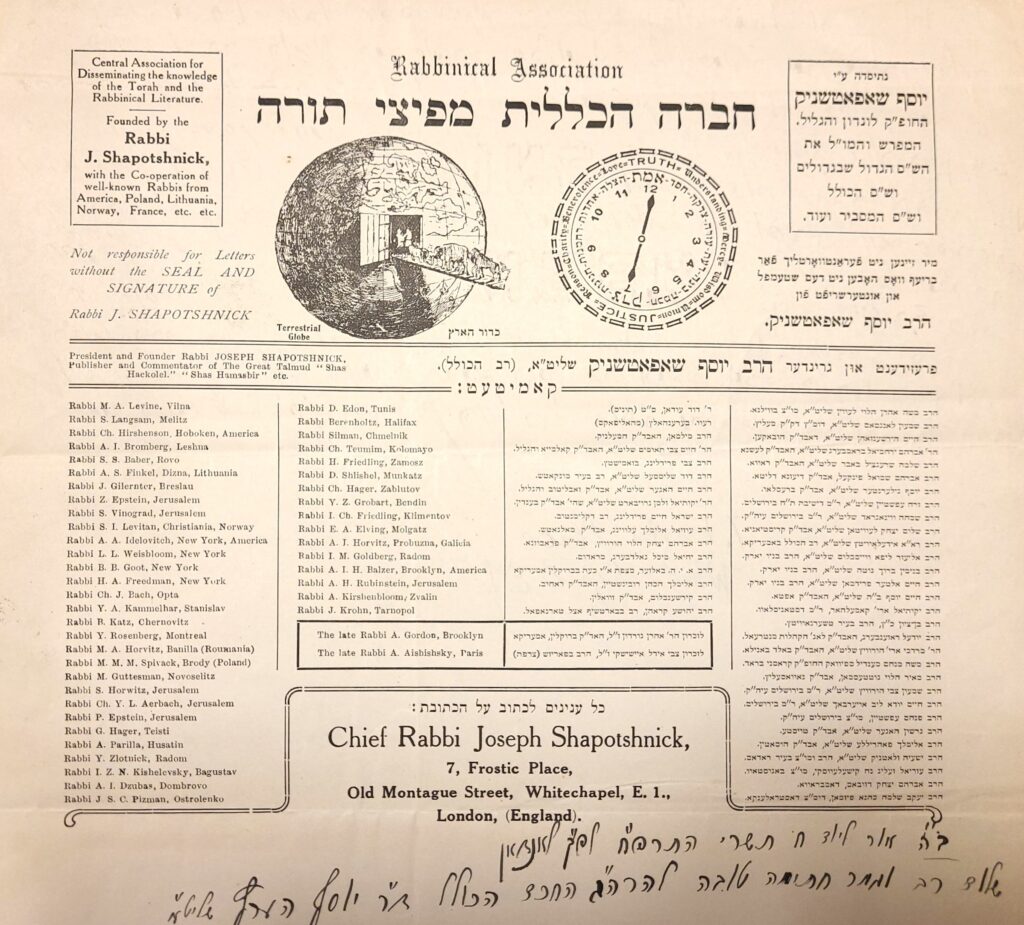

A FICTITIOUS RABBINICAL ASSOCIATION

As part of his strenuous efforts to enhance and magnify his reputation, Shapotshnick ‘founded’ a fictitious international rabbinical organization that he named Hevra Hakellalit Mefitse Torah (“The General Society of Disseminators of Torah”). Any rabbi who had ever corresponded with him was automatically included as a member. Consequently, the names of dozens of rabbis appeared on the organization’s official stationery, apparently without their consent or even their knowledge. And of course, he appointed and promoted himself as the ‘president’ of the organization.

In actual fact, Shapotshnick was a deluded megalomaniac desperate for others to consider him a central figure and celebrated authority of the rabbinic world, and somehow he imagined this could be achieved if he was perceived as the head of an important rabbinical organization. His delusions evolved over time, and in due course he began to promote himself not just as “president”, but as the “chief rabbi”. Indeed, it is even possible that for many Eastern European Jewish immigrants in London, Shapotshnick would have been considered more authentic as a chief rabbi than the much more anglicized Rabbi Hertz.

In his defense and to his credit, Shapotshnick cared deeply for those who were poverty-stricken in his community, and he organized countless successful charitable initiatives. Additionally, he was a genial man who maintained close personal ties with ordinary folk, and he was also adept at addressing audiences, being widely appreciated as an inspiring public speaker. Perhaps if he would have limited himself to acting as a Hasidic rabbi involved in social welfare activities and publishing a variety of scholarly materials, rather than venturing into the vexed world of Jewish family law, he would have remained legitimate, regarded as a colorful character who did good work in a variety of spheres. But by the mid-1920s Shapotshnick had clearly begun to believe his own self-promoting propaganda, a leap that would land him in very hot water by bringing him into conflict with those who were the true experts responsible for the valid execution of Jewish law.

THE AGUNOT SCANDAL

In 1925, seemingly out of the blue and without any evidentiary foundation, Shapotshnick declared that Chief Rabbi Hertz and his leading dayan Rabbi Hillman had granted kosher certification to butchers who were selling non-kosher meat, and that as a result he had decided to establish an alternative kashrut authority for London’s immigrant community. This tactic was often used by immigrant rabbis in the Western world looking to make a name for themselves, and of course money, in cities where kashrut had previously been provided by one central authority.[19]

But in spite of this provocative move, it would appear Rabbi Hillman was willing to absorb the challenge to his authority, and indeed, things might have remained somewhat calm and uneventful had Shapotshnick not decided a couple of years later to set his sights higher by becoming involved in complicated matters of Jewish family law. It was only then that Rabbi Hillman realized it was no longer possible to remain passive, and he hastened to deal decisively with Shapotshnick’s impudent overreach.

In early 1927, Shapotshnick published a pamphlet entitled Likro la’asurim dror (“Declaring Freedom for the Imprisoned”). In it he described the stories of three women whose husbands had died without having had any children. A woman in that situation has to perform what is known as halitza – a biblically mandated ritual involving the shoe of her dead husband’s brother, during which she publicly reprimands her brother-in-law for not marrying her. Only after completing this ritual under the watchful eye of a Beit Din and witnesses is she allowed to get married to another man. For various reasons, in each of the three cases cited by Shapotshnick, halitza was not a viable option, and the women remained unable to remarry, that is to say, they were agunot – the term that is used to describe Jewish women who, as a result of a legal impediment, cannot freely get married.

In Likro la’asurim dror, Shapotshnick proposed a legal loophole for each of the women to remarry without performing halitza.[20] As an experienced rabbinic scholar, Shapotshnick was acutely aware that if he wanted to legitimize such weighty rulings, he would need to attach the names of some rabbinic colleagues to the rulings in order to demonstrate broad consent. It was therefore no surprise that he included the names of several prominent rabbis, whom he claimed – spuriously, as it turned out – had agreed with his radical proposals to resolve the three agunot cases described in his pamphlet.

When Rabbi Hillman read Likro la’asurim dror he immediately realized that Shapotshnick had gone too far. As far as Rabbi Hillman was concerned, Shapotshnick could give himself as many honorific titles as he could come up with, publish as many publications as he wanted, and even set up a rival kashrut agency – it was all okay, just as long as he did not venture into territory that would undermine halakhic norms and cause people problems down the line. Shapotshnick’s readiness to abolish the ritual of halitza was overreach on a totally different level, and it demanded a swift and decisive reaction.

Rabbi Hillman was an experienced rabbinic operator who understood how the Jewish world worked, and he was fully aware that if he ploughed into battle against Shapotshnick on his own, the dispute would be perceived as a power struggle between two feuding rabbis – perhaps worthy of a couple of newspaper reports and some community gossip – but that would be it. Rather, if he wanted to effectively neutralize Shapotshnick’s authority and reputation once-and-for-all, instead of doing it on his own, he would need powerful forces and wise counsel at his side to help him direct and decisively win the battle.

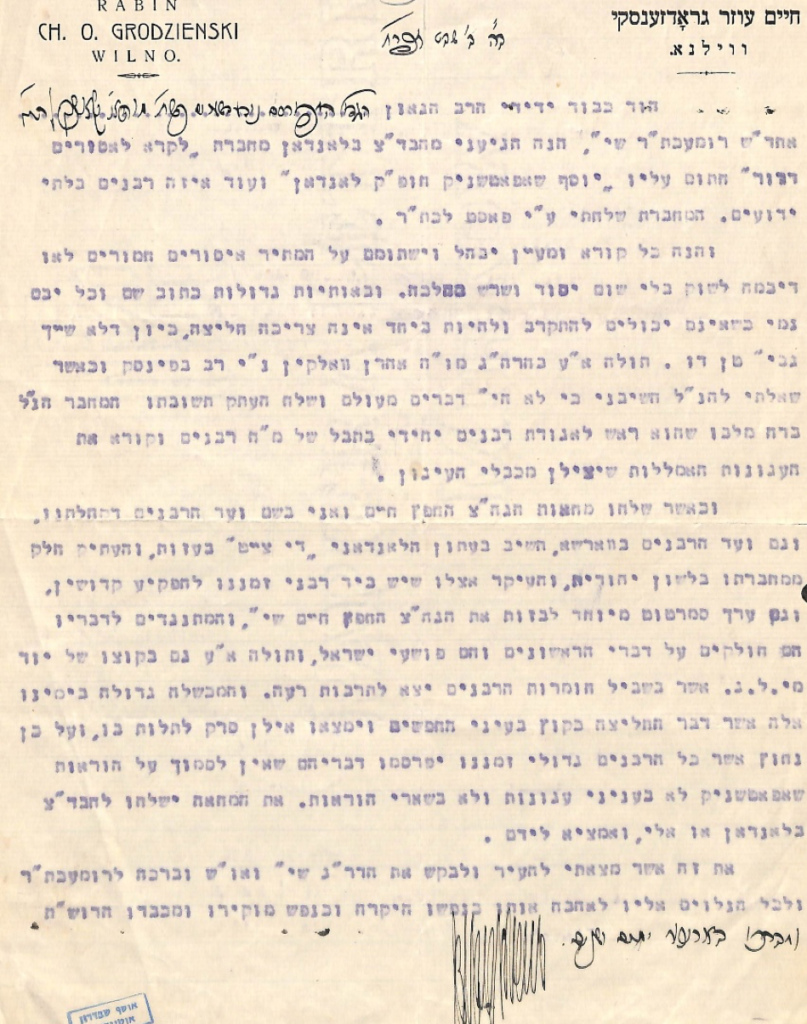

Probably the greatest rabbinic authority at that time was Rabbi Chaim Ozer Grodzinski (1863-1940). Although he resided in Vilna (Vilnius), Lithuania, he was the rabbinical guide to hundreds of Jewish congregations all over the world, as well as the President of Agudat Israel’s Moetzet Gedolei HaTorah (“Council of Torah Sages”). By the time the Shapotshnick episode began, Rabbi Grodzinski had been acquainted with Rabbi Hillman for many years, having regularly corresponded with him on halakhic issues and communal matters, and he held Rabbi Hillman in very high esteem.

Soon after receiving Shapotshnick’s pamphlet, Rabbi Hillman sent the offending publication to Rabbi Grodzinski, seeking his guidance on how to neutralize its influence and the potential damage it might cause. In his letter to Rabbi Grodzinski, Rabbi Hillman also included his personal opinion of Shapotshnick, informing him that Shapotshnick was not really a substantive halakhic expert concerned for the plight of agunot; rather, he was a charlatan looking for fame and fortune, hoping that these controversial halakhic rulings would bring him both.

Rabbi Grodzinski was extremely alarmed by what he read, and immediately composed a harsh letter against Shapotshnick which he dispatched to all the members of the Moetzet Gedolei HaTorah, as well as to several other influential rabbis. Additionally, he penned a powerfully worded letter of support for Rabbi Hillman in his own handwriting,[21] giving him permission to publish the letter using every available medium. He also sent a personal message to Rabbi Hillman urging him to seek out more rabbis who would agree to publicly condemn Shapotshnick’s actions, demanding that he immediately desisted his involvement in any matter to do with agunot.

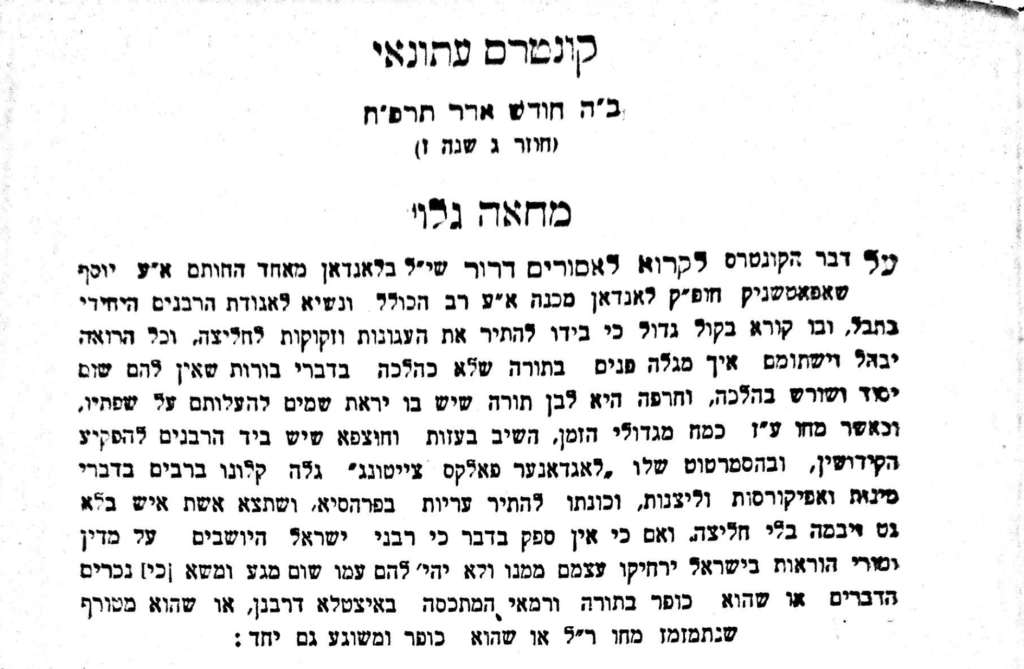

THE PUBLIC CONDEMNATION OF SHAPOTSHNICK

On December 9, 1927, in an extended edition of the London-based Yiddish newspaper Die Tzeit,[22] the center front-page headline announced that “the Chief Rabbi and his court disqualify the position of Rabbi Shapotshnick regarding halitza.” Below that was a sub-headline with an even more shocking declaration: “The greatest rabbis in the world, the Hafetz Hayyim and Rabbi Chaim Ozer Grodzinski, agree with the Chief Rabbi.”

These two headlines were the opening shots in the bitter war launched by Rabbi Hillman against Shapotshnick. This epic battle was unlike any other religious or communal battles previously fought by rabbis and scholars in the British Jewish community, and it would reverberate well beyond British shores. The man behind it, who deftly guided it and strategized every move, was none other than Rabbi Hillman. In his view, Shapotshnick constituted a real and present danger to the sanctity of Judaism and the Jewish people, and it was imperative to wage a comprehensive campaign against him in order to eliminate that threat, and to do so with the frontline support of the era’s greatest rabbis. As it turned out, Rabbi Hillman’s strategy was a rare combination of wisdom, responsibility, leadership and humility.

Crucially, both Rabbi Grodzinski and Rabbi Israel Meir Kagan (1838-1933) – the saintly rabbinic leader known eponymously as the Hafetz Hayyim – lent their full support to Rabbi Hillman. They showed him boundless respect, and extended assistance to him on a scale that had rarely been seen from either of them throughout all their years in the public arena. In each case the letters they sent were unusual, worded more sharply and more harshly than letters issued by them previously regarding other matters.

The letter from Rabbi Grodzinski was published in full in Die Tzeit:

The London Beit Din has sent me a copy of the pamphlet Likro la’asurim dror which bears the name of ‘Joseph Shapotshnick of London’ as well as the names of several other rabbis. When I read it, I was shocked and disturbed by this person who declares freedom for [agunot] by permitting serious prohibitions… allowing a levirate woman to remarry without halitza in a manner that has no basis or source in halakha, rather [the pamphlet is full of] facts that make no sense, and also errors. The facts as he presents them do not correspond to reality, and in his sourcing of legal material he presents bottom-line conclusions using excerpts from rabbinical discourse that were only said by way of “let us consider”, or as stages in a longer discussion, or as tangential considerations.

And all of this [has been done] to mislead his uninformed readership. Anyone who knows and understands the source material and the core halakhic issues involved can identify and see through the errors and pitfalls inherent in this work, and [they know] that it stands contrary to Talmudic law as well as to the words of our rabbis, [both] Rishonim and Aharonim.[23] This is not the place to discuss the [relevant] Torah law [in detail], matters which are understood only to those who study Talmud in depth and [know] how to set down halakhic rulings.

[Furthermore,] I absolutely do not believe him regarding the other rabbis he attests as assenting to his position, seeing as how one of the distinguished rabbis whom he says agreed to his lenient ruling wrote to me saying he never gave such a permissive ruling and that [Shapotshnick’s] claim is a complete lie. Woe unto our generation that we experience such a thing – that someone calling themself a rabbi and a teacher makes such a grave error and causes others to err along with him in a matter of halakha concerning Torah prohibitions and the severest of forbidden relations.

If [Shapotshnick] had been a Reform [rabbi], who does not believe in the sanctity of Torah law – seeing as [the Reform movement] take stances against the words of both the Written and Oral Torah, and their leaders as a matter of course make whatever rulings they individually feel like making, for that is their way – I would not have been so surprised. [If this was the case,] ordinary [Jews], who are believers the children of believers, who embrace tradition, would pay no heed [to Shapotshnick’s rulings]. But remarkably, in this case a man known as a[n Orthodox] ‘rabbi’ and a ‘teacher’ has set out to do something eye-catching, [as if he is] basing himself on the foundations of Torah and relying on the great teachers, when in reality his aim is to upend and neuter their words and to uproot a Torah prohibition – should we not tear our clothes in mourning upon hearing the awful news of such rulings?!

His heart has swelled [with arrogance to such a degree] with this [lenient] ruling, that he openly and explicitly admits in his pamphlet that he has established a “dispensation factory” in London for the express purpose of freeing agunot and those indefinitely awaiting levirate marriage, as if advertising to [all] the agunot: “Come to me and I can free you from your imprisoned status.” He has also come up with this notion that he is the head of the most important rabbinical organization in the world – and we know that our Mishna teaches us about this [behavior] that “he whose heart is presumptuous in giving a judicial decision, is foolish, wicked and arrogant.”[24]

This, his ruling, is no ruling – it is a mistake, a pitfall, and carelessness in the most serious matters of forbidden sexual relations. It is the responsibility of the great leaders of Israel in all parts of the Diaspora to reprimand and censure this attempt, and not to rely on his rulings in any way at all. It pains me greatly to attack the honor of any person, but in order to remove a stumbling block I consider myself responsible to do just that, and to widely publicize this viewpoint in my name and in the name of my colleagues, great rabbis, righteous teachers of our community. We wish that [Shapotshnick] would come to his senses and come back to the ways of truth, no longer misleading people, saying publicly “what I said was in error.”

Written with deep sorrow over the lowering and forgetting of the Torah, and the decline of religious faith in our time, awaiting Salvation – written and signed on Sunday, 25 Marcheshvan, 5688 [1927], in Vilna. Chaim Ozer Grodzinski

Letter from R. Chaim Ozer Grodzinski about Shapotshnick

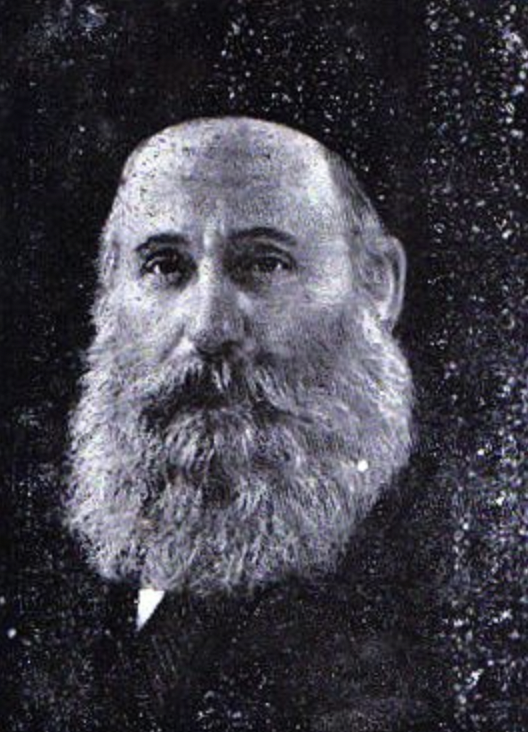

The Hafetz Hayyim also responded to Rabbi Hillman’s request by writing a condemnatory letter. He clearly recognized the great danger posed by Shapotshnick’s actions, and although his letter was shorter than Rabbi Grodzinski’s, it must be regarded as having great – almost immeasurable – importance, as it was written by a universally acknowledged saintly man who was particularly revered for the great care he had taken throughout his life to prioritize the importance of refraining from speaking ill of others.

I received [Rabbi Hillman’s] letter along with the pamphlet Likro la’asurim dror. Truly, I feel great distress that such a thing has come to pass in our time: that there are young men who wish to ascend to the mountaintop, and to gain notoriety for themselves by delving into the serious issues of forbidden relationships, and being blithely permissive regarding prohibitions and heavenly retribution [for those who transgress these prohibitions]. But, to my regret, it is very difficult for me in my old age, weakened in strength, to go out with a broad public denouncement and to join in the fray. Therefore, I am simply making known my distress and [Rabbi Hillman’s] distress to the great people in our places [of residence], and surely they will reply – to write and determine what is to be done with this pamphlet… Israel Meir HaKohen of Radun[25]

Rabbi Grodzinski had also widened his campaign on Rabbi Hillman’s behalf by appealing to a whole range of rabbis, and as part of that drive had reached out to Rabbi Avraham Yaakov HaLevi Horowitz (1864-1942), a Belzer hassid who was the rabbi of Probizhna, Poland (today Ukraine), considered a leading authority on the freeing of agunot. In his letter to Rabbi Horowitz, Rabbi Grodzinski asked him to examine Shapotshnick’s pamphlet and weigh in on what it said. Rabbi Horowitz responded to Rabbi Grodzinski in a letter written in clear and pointed language that was later published in his book of halakhic rulings:

Regarding the pamphlet sent to me… printed in London, bitterly condemned because it attempts to rule leniently… I was surprised to see a senior person like [Shapotshnick] involved with such nonsense, permitting … a leniency [regarding a] Torah prohibition with his prattling … woe unto the generation that such a thing has come about in its time, that a rabbi who sees himself as a great [leader] of the generation would engage in this drivel and mislead the public … I have absolutely no idea how he thought it was okay to permit such serious prohibitions with empty rhetoric and blather. May God have mercy on us to raise up the Torah so that scoundrels [like Shapotshnick] do not come and profane it. [Shapotshnick’s] words have no place within the gates of Torah, so I hope your pure heart will worry no further, for it is apparent to all that his words are idle and void.[26]

CHIEF RABBI HERTZ AND THE BRITISH RABBINATE CONDEMN SHAPOTSHNICK

In the same edition of Die Tzeit that contained the letters of Rabbi Grodzinski and the Hafetz Hayyim there was also a brief statement issued by the office of Chief Rabbi Hertz and the dayanim of his Beit Din:

This is to inform you all that Rabbi Joseph Shapotshnick, who is not connected in any way with the official community, despite the fact that he calls himself “Chief Rabbi,” recently claimed that he could free widows who have no children from the religious requirement known as halitza. We wish to formally declare that the Chief Rabbi and the Beit Din totally invalidate and denounce this statement, this decision, this measure of Rabbi Shapotshnick [which he] recently promoted in newspaper announcements and via pamphlets… [This whole idea] is based on an inaccurate portrayal of facts and is completely against Jewish law.[27]

Many of the senior rabbis from across Britain attached their support to the Chief Rabbi’s statement, which had in actual fact been written by Rabbi Hillman: Rabbi Yaakov Rabinowitz (d.1932) of Dalston, London; Rabbis Yisrael Chaim Daiches (1850-1937), Tzvi Hurwitz (1863-1946), and Yehuda Leib Ostrinski (1881-1946) of Leeds; Rabbis Yisrael Yaakov Joffe (1875-1934) and Tzvi Hirsch Levin of Manchester; Rabbi Isser Yehuda Unterman (1886-1976) of Liverpool; and finally Rabbi Yitzchak Isaac HaLevi Herzog (1888-1959) of Dublin, Ireland, who was Rabbi Hillman’s son-in-law. These last two would both later be appointed Chief Rabbis of the State of Israel.

Rabbi Hillman also made sure to secure the support of his colleagues in the Beit Din: Rabbi Asher Feldman (1873-1948), Rabbi Yehuda (Louis) Mendelssohn (1868-1948), and Rabbi Tzvi Meir (Harris) Lazarus (1878-1962) – although it must be said that these rabbis were never trained as dayanim and were certainly not accepted as rabbinic scholars by the immigrant community. It was for precisely this reason that Rabbi Hillman also had to win the support of the other aforementioned rabbis, as they were acceptable to the immigrant community based on the fact that they were known as rabbinic scholars – a rare commodity in Britain at that time. Additionally, by promoting the broad support by a range of rabbis for the anti-Shapotshnick campaign, Rabbi Hillman was able to keep himself out of the spotlight while still achieving the desired result.

Apparently, Shapotshnick knew what was coming, and had vainly tried to land the first blow in the fight with Rabbi Hillman. Two weeks before the matter of his agunot rulings came to light, he sent a letter to Chief Rabbi Hertz with a warning not to heed Rabbi Hillman’s opposition to his stance on the agunot issue: “God forbid that you follow in the path of the dayan, you-know-who, whose name isn’t worth mentioning, who is lucky to have been born in the twentieth century, because if he had lived at the time of the Sanhedrin he would have been ruled a Zakein Mamre (“rebellious elder”).[28] And even though I am sure this judge will remain in the Beit Din all his life, nevertheless I hope that a great sage [like yourself] will not pay heed to the empty words he utters.”[29]

Of course, “the dayan, you-know-who” was Rabbi Hillman, who was doing everything he could to ensure that halakha was being properly upheld, and who was more than willing to take on a con-artist like Shapotshnick. It is noteworthy that Chief Rabbi Hertz never replied to this letter from Shapotshnick. Unlike his predecessors, he knew the bounds of his own expertise, and was totally confident relying on Rabbi Hillman’s judgment in these matters.[30]

Rabbi Hertz (seated, 2nd left) and Rabbi Hillman (seated, 2nd right) at the London Beth Din

Significantly, Rabbi Hillman was utterly unique. In all the history of Anglo-Jewry there was never anyone else like him – a scholar of stature for whom the entire leadership of the community, including the Chief Rabbi, gave all necessary resources and trust to strengthen Judaism at every level, and to do whatever needed to be done to ensure that there was no desecration of God’s name. The Shapotshnick agunot episode simply epitomized his ability to use this wide latitude in the best possible way.

On Monday, December 12, 1927, an article appeared in Die Tzeit titled “What is halitza?” The byline named Morris Myer, the paper’s editor. It was the first in a three-part series of comprehensive articles that went into great detail regarding the halakhic issues of halitza and agunot. The level of detail indicates that these articles must have been prepared well in advance of their publication, as their style was very different from that of a regular Die Tzeit article. Written with clarity and precision by a person who had a great deal of knowledge and insight into the relevant topics, it cited sources that were both pertinent and contemporary.

For this reason, I find it extremely difficult to believe that Morris Myer authored these articles. He was neither a halakhic scholar, nor could he have prepared three comprehensive essays such as these on short notice, or indeed at all. Rather, we must presume that these articles were written by Rabbi Hillman, and that he surrendered the byline to Morris Myer to make them more acceptable to the immigrant readership of Die Tzeit. By doing it this way he would deftly steer the public discourse, while at the same time shielding his reputation and office – keeping himself safely out of the line of fire. This is further evidence of the extent to which Rabbi Hillman planned the Shapotshnick takedown campaign, with the focus on success rather than self-promotion.

The first article began with a preamble explaining that the idea behind printing the three articles was to help Die Tzeit readers gain a broader understanding of the struggle that was going on between Shapotshnick and the rabbis who opposed him; the unspoken but understood implication was that the readership lacked the required level of scholarship that would enable them to automatically understand this relatively obscure area of Jewish family law. Once again, Die Tzeit’s editor was at pains to emphasize that both he personally, and the newspaper he led, were not taking sides in the dispute, nor would they ever favor one or another of the disputants in this battle. Moreover, he assured his readers that Shapotshnick would have an opportunity to respond. But the truth was somewhat different; Morris Myer clearly understood that he needed to project his ‘neutral’ role to ensure the success of Rabbi Hillman’s efforts.

The second article in the series was published the following day, alongside some comments by Shapotshnick, his first public remarks since the controversy had flared up.[31] His main contention was that the attacks against him were not due to disagreements regarding the agunot he had freed, but rather in retaliation for his having challenged the Chief Rabbi’s monopoly on the granting of kosher certificates to butchers. He concluded by insisting – recklessly, as it turned out – that his attackers had no other critical letters against him that they could publish.

On Sunday, December 18, additional letters against Shapotshnick from a range of internationally renowned rabbis were published in the Die Tzeit. Among them was a letter from Rabbi Moshe Mordechai Epstein (1866-1933), Rosh Yeshiva of Knesset Yisrael-Slabodka, who lived in Hebron, where his yeshiva had relocated a couple of years earlier. Rabbi Epstein was one of the best-known and most-respected yeshiva heads in the world, a mild-mannered man not identified as having strong opinions or an eagerness to involve himself in controversy. Despite this gentle reputation, in this situation, without mincing his words, he expressed his utter disgust with Shapotshnick’s pamphlet.

Rabbi Moshe Mordechai Epstein

Rabbi Epstein declared that Shapotshnick’s preposterous interpretations of the relevant areas of Jewish law as utterly inadequate to permit any of the three women mentioned in Likro la’asurim dror to remarry; each of them would require halitza before getting married. Rabbi Epstein also posited that Shapotshnick did not really have any outside backing from reputable rabbinic authorities as he claimed. Once the rabbis whom Shapotshnick had alleged supported his rulings would discover what had been written in their names, said Rabbi Epstein, they would immediately and publicly repudiate all of Shapotshnick’s claims. As it turned out, this was a statement that verged on the prophetic.

On December 20, a new salvo appeared in Die Tzeit in the form of an unequivocal letter from the Rabbinical Council of Warsaw, a highly respected rabbinic organization with decades of experience. The Warsaw Rabbinical Council was often called on to weigh in with their opinion regarding big-ticket communal and halakhic disputes, usually in Poland, but from time to time, as on this occasion, in other countries. The rabbis on this august body were recognized as the greatest experts in Europe on the issues of Jewish divorce and agunot. Hundreds of couples came to them each year to be divorced in accordance with Torah Law.

These rabbis were certainly the best-positioned of all the rabbis in Europe at that moment in time to know exactly under what circumstances agunot could be “freed”. On that basis, their opposition to Shapotshnick’s rulings was extremely significant. In their letter, the rabbis stated that Shapotshnick was a scoundrel and that all his words should be dismissed: “We protest with all our might against the rulings contained in [Shapotshnick’s] pamphlet, and not a single Jew is allowed … to rely on such judgments for practical purposes. Moreover, anyone God-fearing person … is obligated to publicly denounce him.”

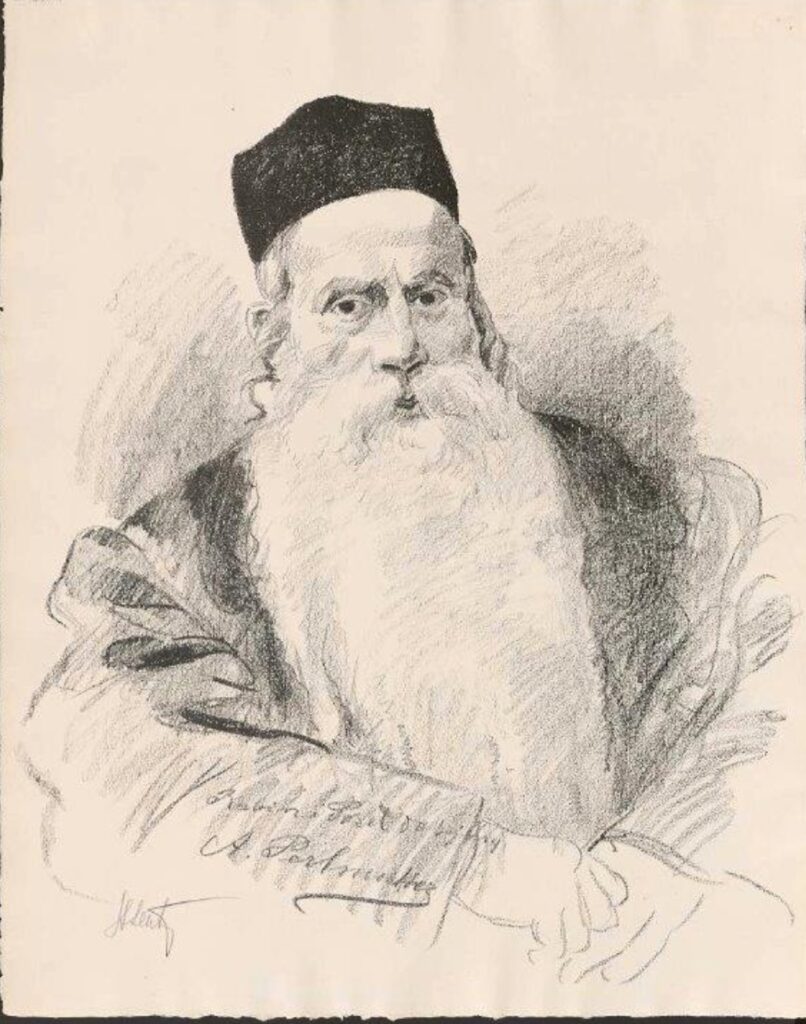

The letter was signed by the elderly Chief Rabbi of Warsaw, Rabbi Avraham Tzvi Perlmutter (1843-1930), along with Rabbi Chaim Yehoshua Gutschechter (1860-1942), Rabbi Shlomo Dov Kahana (1869-1953), Rabbi Tzvi Yehezkel Michelsohn (1863-1942), Rabbi Yizhak Meir Kanal (d.1942), Rabbi Chaim Posner (1870-1939), Rabbi Yaakov Zilberstein (1880-1941), Rabbi Chaim Leib Yudkowsky (d.1934), Rabbi Aharon Scheingross (1855-1937), and Rabbi Menahem Shakhna Ritschewol (d.1931).

These were all very serious names. Rabbi Perlmutter was, in addition to being head of the Warsaw Beit Din, an active member of the Polish Sejm (parliament). Rabbi Gutschechter, who had studied under the world-renowned Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik of Brisk (Brest-Litovsk) when he had taught at Volozhin yeshiva, was known to be the key rabbinic judge at every case brought to the Warsaw Beit Din. Rabbi Kahana was an internationally consulted expert for all the most difficult agunot cases – to the extent that he was known by the nickname av ha-agunot (‘father of the agunot’) – and he toiled tirelessly to find ways to free agunot from their halakhic disability.

Rabbi Avraham Tzvi Perlmutter

The other rabbis were all similarly well-known, individually and collectively, as men of great learning and even greater integrity. Simply put, if they were ready to write off Shapotshnick’s rulings as unworkable, then all his efforts on behalf of agunot were dead in the water. Indeed, this letter was a devastating blow to Shapotshnick, and Rabbi Hillman must have felt that even if Shapotshnick responded with an ill-mannered riposte, the fight had been won, and Shapotshnick’s already tattered reputation had been demolished with a knockout punch. But unbeknownst to Rabbi Hillman, his adversary still had an ace up his sleeve, as would be revealed in Die Tzeit the following morning.

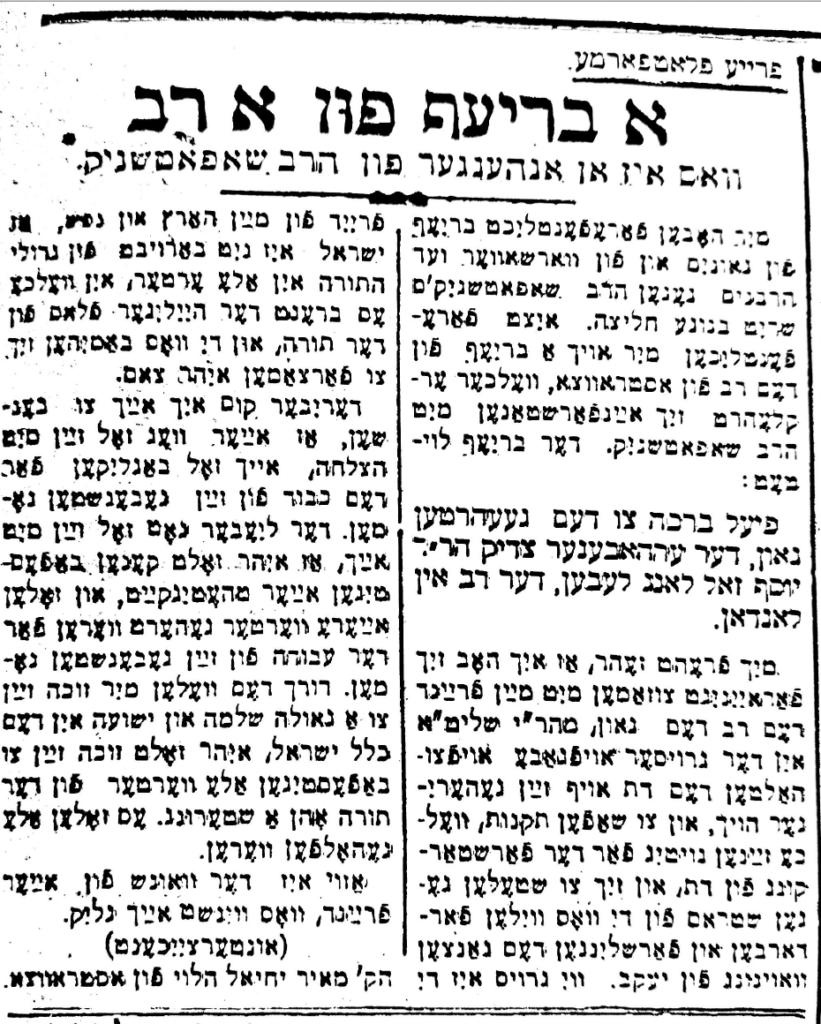

THE OSTROVTZA REBBE WEIGHS IN

Shapotshnick’s unexpected response appeared in Die Tzeit the next day, and in his own privately published newspaper a few days later. It amounted to a warm, wholehearted letter praising Shapotshnick’s efforts to strengthen Judaism, and offering him fulsome support in the battle against his detractors: “So great is the joy of my heart and soul, that the people of Israel are not without great men of Torah wherever they are, within whom the flame of the Torah burns, and they endeavor to bring it to everyone…”

The author of this obsequious letter was the highly revered Rabbi Meir Yechiel Halevi Halstock (1851-1928), who was both the rabbi and ADMO”R[32] of Ostrowiec (in Yiddish pronounced ‘Ostrovtza’), but more importantly the most senior Hasidic “rebbe” in Poland. Rabbi Halstock’s fawning letter went on to describe Shapotshnick as a very righteous man whose intentions were all for the sake of Heaven, and moreover, Rabbi Halstock expressed his complete support for his faithful friend “the rabbi, the gaon, Yosef Shapotshnick.”

Jarringly, the Ostrovtza Rebbe concluded his letter with intimate words that would only ever be communicated by an unabashed admirer: “your friend, who asks you for a blessing” – and he then blessed Shapotshnick with success in all his endeavors, which, he said, would “surely bring the [Messianic] Redemption ever closer.”

The Ostrovtza rebbe’s letter in Die Tzeit

After the unexpected publication of this incredible missive, the question uppermost in everyone’s mind was – how exactly had Shapotshnick managed to procure such a powerful endorsement from this A-list rabbi? The letter cast serious doubt on those who had dismissed him as a charlatan – after all, would a truly great man like the Ostrovtza Rebbe praise a faker, even going so far as to seek his blessing? But the truth, when it emerged, would reveal a calculated cunning that had resulted in this letter, a cunning which would prove to be Shapotshnick’s unfortunate hallmark.

Months before the concerted campaign against Shapotshnick was launched in the pages of Die Tzeit, he had already anticipated the attacks that would be leveled against him and carefully prepared a counter-campaign to launch when it became necessary. Accordingly, he had sent a letter to – among others, no doubt – the Ostrovtza Rebbe, a holy man but very elderly and not in good health. Shapotshnick’s letter had spun him a story regarding the dismal state of Jewish religious life in London, claiming that he had launched a ‘holy war’ against violators of the faith.[33]

Of course, Shapotshnick said nothing in his letter to the aged rabbi about his halitza rulings, nor about his pamphlets and newspapers, nor indeed about the letters issued against him by great rabbis such as Rabbi Grodzinski, although at that stage the letters were not yet public.

The Ostrovtza Rebbe, perhaps as a result of his fragile health, believed what Shapotshnick had written to him, never suspecting for a moment that there was another agenda at play. Indeed, his letter of support was written in November, a few weeks before the controversy erupted.

In his privately published newspaper, Londoner Folks Tzeitung (“London People’s Newspaper”), Shapotshnick used the Ostrovtza Rebbe’s letter as the basis for an outright attack on the various rabbis who had come out publicly against him, and he also added a long list of rabbis who he claimed supported him.

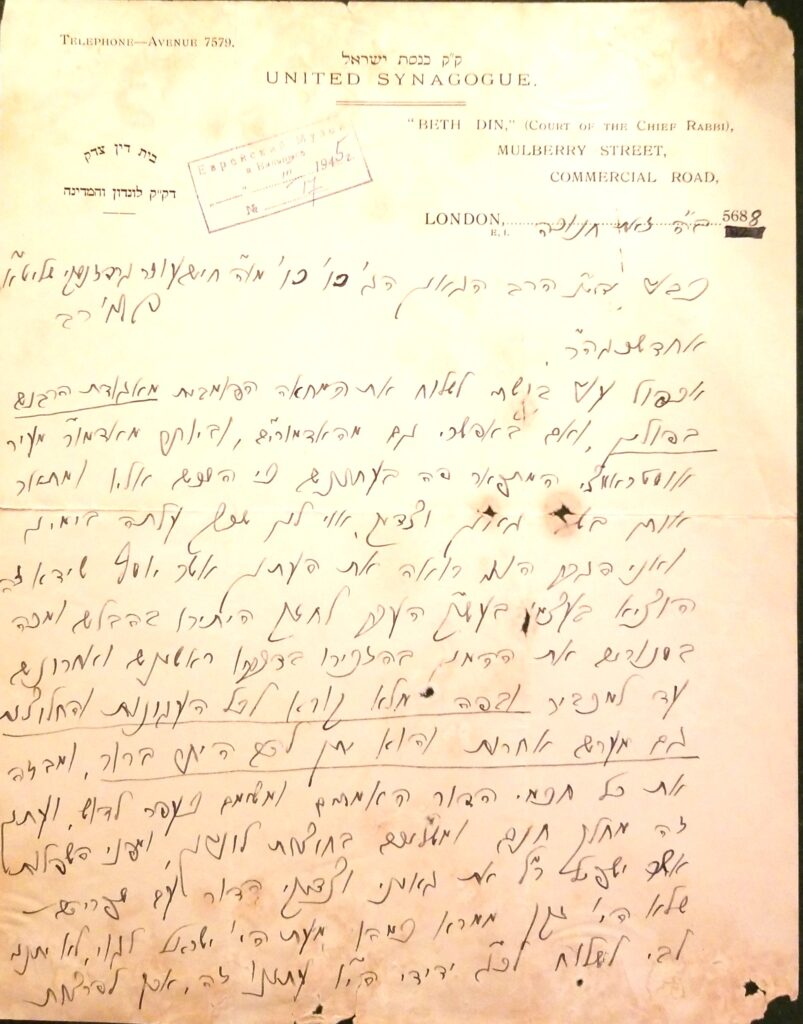

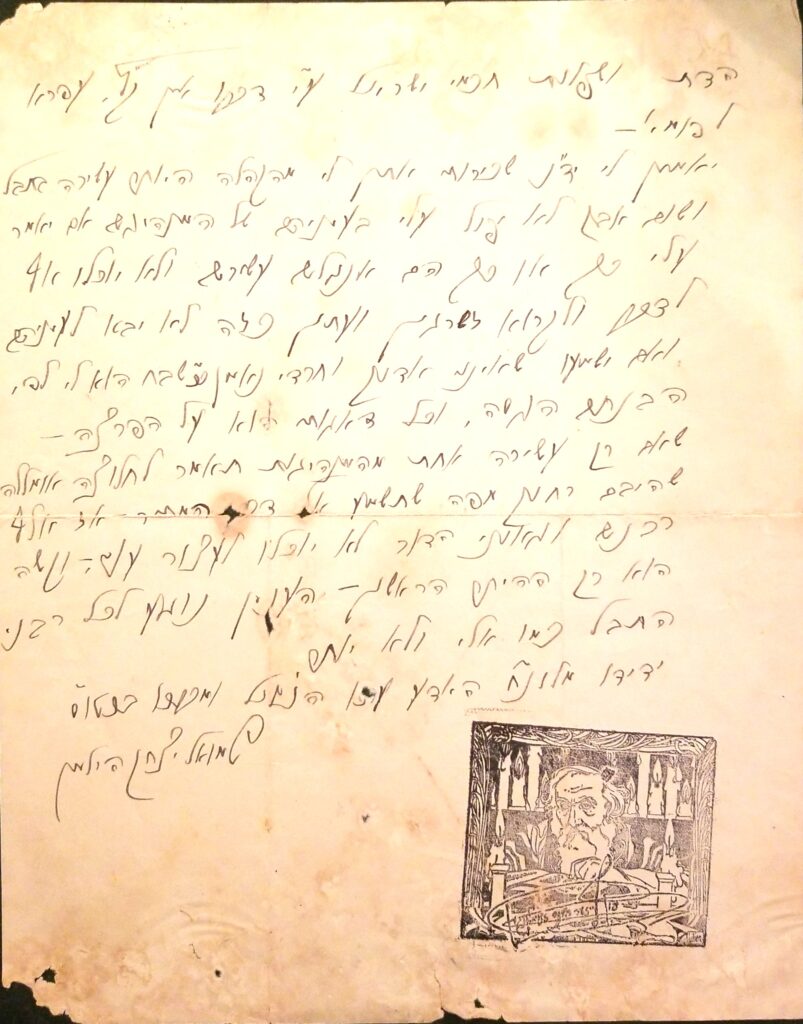

RABBI HILLMAN’S LETTER TO RABBI GRODZINSKI

This new twist was a devastating blow to Rabbi Hillman, and a few days later, on December 27, he sat down and poured out his heart to Rabbi Grodzinski in a plaintive letter. Once again, he asked for his illustrious colleague to help him in neutralizing the threat to Jewish law and to the rabbinate that arose from Shapotshnick’s activities:

I repeat my request for you to send me a copy of the public protest issued by the Rabbinical Association of Poland, and if possible also the one issued by the Hasidic rebbes and especially from the rebbe of the town of Ostrowiec, who Shapotshnick has boasted … has given him his approval and referred to him as a scholar and a righteous individual.

Woe to us that such things have occurred in our days! I have seen the newspaper that this demon Joseph [Shapotshnick] published last Friday,[34] to support his lenient ruling with nonsense, and to blind the masses by quoting at length the words of medieval and contemporary rabbinic authorities. In a loud voice he calls out to all agunot and women who require halitza – including those from elsewhere – [to come to him] and he guarantees them a lenient ruling [so that they can marry]. He also ridicules all the true sages of the generation and treats them like dust. He distributes this paper free-of-charge and throws them into the streets of London. Because of the way he humiliates the sages and saints of our generation and their works – never has there been a rebellious scholar like him in our history! – my heart does not allow me to send this newspaper to [you] my dear friend. However, there is no end to the breaches in our faith and humiliation of the sages of Israel that result from his unending words – may his mouth be filled with earth!

Believe me, my dear friend, I receive my wages from the wealthiest community in the world, and I will not be tarnished in the eyes of its leaders, whatever [Shapotshnick] says about me. They are wealthy Englishmen who cannot speak or read Yiddish, and they have never even seen his newspapers. If they were to [think after hearing what he says] that I am not so strictly-Orthodox, according to their coarse understanding they would consider it a compliment. My only concern is about the [potential] breach [of Jewish law resulting from Shapotshnick’s activities] – if there is just one wealthy woman from among the leaders of the community who tells an unfortunate woman requiring halitza whose brother-in-law lives far away that she should listen to the words of this [charlatan] – even a thousand rabbis and the generation’s leaders will not be able to stop it [from getting out of hand]. It is only the first lenient ruling that is the problem [as afterward it will be considered a precedent]. This is a problem that affects rabbis around the world as much as it affects me, or even more so.”[35]

Rabbi Hillman’s letter to R. Chaim Ozer Grodzinski

Rabbi Hillman’s sincerity is noteworthy. It was clear to him that if he agreed with Shapotshnick on this matter his employers might actually be happy with him. Most of them were not Torah observant – and if they became aware of the extent of the dispute between him and Shapotshnick it might harm him, as it was perfectly possible that they would be sympathetic to Shapotshnick’s more ‘liberal’ ideas. It was even possible that Chief Rabbi Hertz himself would go along with Shapotshnick’s nonsense, if sufficient pressure were exerted on him. This was why Rabbi Hillman was trying to arouse enough opposition and negative publicity against Shapotshnick from every quarter, in order that no aguna would ever think of showing up at Shapotshnick’s door and seeking his spurious dispensations to remarry.

SHAPOTSHNICK’S VERSION OF EVENTS

In that same edition of Londoner Folks Tzeitung mentioned by Rabbi Hillman in his letter to Rabbi Grodzinski, Shapotshnick also published his version of events in an attempt to justify his position and to undermine Rabbi Hillman’s attempts to derail his activities. According to him the whole agunot saga had actually started in 1925. An unnamed woman requiring halitza walked into the London Beit Din on Mulberry Street and asked the dayanim for their help. After examining the details of the case, the Beit Din informed her there was absolutely nothing they could do to assist her with her problem and sent her away. In desperation, the woman turned to Shapotshnick who looked into the matter and authored the by-now famous ruling that had suggested seventeen separate reasons to be lenient.

Armed with Shapotshnick’s ruling, the woman returned to the Beit Din, this time accompanied by a respected communal activist – kosher wine merchant called Elias Frumkin (c.1880-1958).[36] Unable to dismiss her as they had when she first sought their help, the dayanim asked her to leave the detailed ruling with them so that they could look it over, and promised to revert to her within five days. Three days later they summoned Frumkin back to Mulberry Street and informed him that they had approved the ruling and that the woman could remarry without having to undergo halitza, which she did, claimed Shapotshnick, on 28th June 1925, at Nelson Street Synagogue.[37]

Conscious of the fact that his testimony regarding this whole affair might not be taken at face value, Shapotshnick suggested that anyone who wanted to confirm the story could do so by contacting Frumkin, or the secretary at Nelson Street Synagogue. Clearly, said Shapotshnick, the Beit Din had hoped that they could keep the whole thing a secret, as it was embarrassing for them to have to admit they had relied upon his dispensation, particularly after they had previously rejected the possibility of a lenient ruling.

Shapotshnick concluded his piece by viciously attacking Rabbi Hillman, identifying him as someone who had authored a book of Talmudic commentary that was full of mistakes, and as the man responsible for allowing the burial of a Jewish convert to Christianity in a Jewish cemetery. Rabbi Hillman had also refused to allow the other two agunot to remarry using his rulings, said Shapotshnick, as he had claimed the rabbinic endorsements were forged. The accusations against Shapotshnick were motivated by hatred born of jealousy and shame generated by the fact that he had not been able to come up with his own lenient rulings. Moreover, added Shapotshnick, if the first ruling had been good enough for Rabbi Hillman to use, then the last two should be good enough too. But despite advice from others that he should sue Rabbi Hillman for libel and slander, Shapotshnick declared that he would act magnanimously, as a public battle between rabbis in a non-Jewish courtroom would be very unseemly.

By this stage of the controversy, it would have been clear to anyone objective that something was not quite right about Shapotshnick. Whether this was because he was mentally unstable, or whether it was because he was thoroughly dishonest, his behavior raised some pretty big questions about his credibility as a rabbi. But the question still remained: was it true that the Beit Din had relied on his first dispensation? Rabbi Hillman’s perennial antagonist, Menashe Adler, certainly thought so. Shapotshnick himself was convinced of it. Significantly, the aguna in that case had been allowed to remarry under the auspices of Rabbi Hillman and his Beit Din without having undergone halitza. The point is, if they had indeed used his ruling, then Shapotshnick had raised a valid point about their refusal to use his second and third rulings; and if they had not relied on his dispensation, how had they ever allowed the first aguna to get remarried under their auspices?

A possible answer came in the form of a letter from Elias Frumkin, published on the front page of the Die Yiddishe Post, another of London’s Yiddish newspapers, on 30 December. Under words ‘lema’an ha-emet’ (for the sake of truth), Frumkin stated:

As Rabbi Shapotshnick has mentioned me [in his newspaper] as a witness [to the fact] that the London Beit Din sanctioned his dispensation for a [woman requiring] halitza [to remarry without halitza], I wish to let it be known that when I originally came with his ruling to the Beit Din they became very agitated [about the fact that he had issued] such a ruling. Afterward the Beit Din discovered other reasons [to be lenient], and on the basis of these new reasons they issued their [own lenient] ruling.

Frumkin concluded his statement in the newspaper by adding that his wife was also familiar with the facts as they had happened, implying that she could be contacted to verify the information if anyone was minded to ask her. Frumkin did not deny the fact that the woman in question had remarried, rather he insisted that this was not because the Beit Din had relied on Shapotshnick’s dispensation. Instead, it was because they had managed to come up with their own reasons to be lenient. In any event, on the basis of this version of events, Shapotshnick’s indignation and protestations of the Beit Din’s dishonesty and hypocrisy does seem to have been misplaced.

Shapotshnick’s only response was to challenge the Beit Din to show him any extra facts they had uncovered to allow for their leniency, and he even offered to publish them at his own expense, adding that “for every new reason … they can find besides for my seventeen points I will by them….a bottle of liquor.”[38] Implying that he thought Frumkin had somehow been pressurized to change sides and malign him, he promised that if the Beit Din won the bet, he would gladly buy the liquor from Frumkin.

SHAPOTSHNICK’S ATTACK AGAINST THE HAFETZ HAYYIM

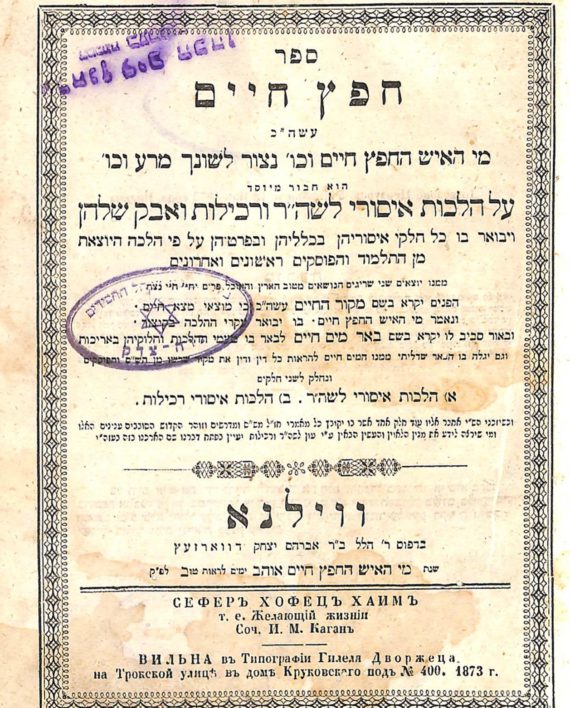

If there was one thing that united the entire Orthodox world, it was an enduring adulation for the Hafetz Hayyim. Considered a paragon of virtue already in his youth, in his old age he was venerated like a saint. His advice was cherished, and his books were revered. On that basis, Shapotshnick’s decision to write a detailed polemic against the Hafetz Hayyim and his magnum opus of the same name must surely rank as the most stupid thing he ever did. For those who may have sympathized with Shapotshnick’s predicament until then, his decision to publish an attack against someone universally acknowledged as a man of supreme piety must have surely driven them into the camp of his opponents. And as for his opponents, the published attack was a gift they could not ever have hoped for, or even dreamed of.

The book entitled Hafetz hayyim, published in 1873, was unique for many reasons. It demonstrated, for example, the author’s familiarity with the length and breadth of Bible, Talmud andJewish ritual law. It was also a testament to the author’s originality and brilliance. But principally it was unique because it shifted the entire focus within Judaism vis-à-vis the topic of gossip and slander from the realms of ethics and morality to the arena of legal requirement.[39]

The most significant contemporary critic of the Hafetz Hayyim’s approach to this subject was Rabbi Shlomo Zalman ha-Kohen Kook (1844-1929), father of Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak Kook, whose annotations on the book Hafetz Hayyim reflected respectful disagreement with its author for turning this area of Judaism from moral aspiration into legal obligation.[40] Other contemporary scholars also noted that by codifying certain aspects of gossip in this unprecedented way, the Hafetz Hayyim was turning law-abiding faithful Jews into almost certain sinners.[41] But all such reservations were muted, and, as a matter of fact, Rabbi Kook’s criticisms were not published until 1970, more than forty years after his death, and almost forty years after the death of the Hafetz Hayyim!

Title page of first edition of Hafetz Hayyim, 1873

The Hafetz Hayyim’s flawless character and his unblemished record as a spiritual leader meant that he was, for all intents and purposes, beyond criticism, and his works were guaranteed automatic entrance into the canon of the Jewish legal code, even during his lifetime. That being the case, the appearance of a section in Shapotshnick’s newspaper devoted to a forceful critique of the Hafetz Hayyim, was, to say the least, ill-advised.

Shapotshnick began by identifying the underlying problem of the Hafetz Hayyim’s work, namely its heavy reliance on homiletic and other non-halakhic sources to derive laws and sub-laws prohibiting gossip and slander.[42] ‘According to his philosophy,’ said Shapotshnick

If someone volunteers his opinion about a cantor or a religious functionary one would be able to find him guilty of countless prohibitions, which begs the question: according to [the Hafetz Hayyim], how many prohibitions did the RABaD[43] transgress, Heaven forbid, when he wrote his critique of Maimonides?

Shapotshnick also picked up on the point that the Hafetz Hayyim’s work was almost entirely original, with no previous codifier ever having felt the need to collect up and codify all the laws of gossip and slander. Was it possible, he asked, that in the 800 years since Maimonides had first codified Jewish law, but having omitted the laws of gossip brought by the Hafetz Hayyim, that all Jews who had ever worried about meticulously observing Jewish law had transgressed the many prohibitions listed by the Hafetz Hayyim simply because they had not been informed of their existence?

There were some people who maintained that creating a set of laws to regulate these matters was ultimately innocuous and would not cause anyone any harm. But Shapotshnick disagreed. He recalled a battle he had fought soon after moving to London when he had tried to ensure that ground matza-meal sold for Passover use was not produced from hametz, which was certainly the case if the matza-meal was white in color. Overall he had been successful in his campaign, but there were those who opposed him – devotees of the Hafetz Hayyim who refused to cooperate on the basis that they were not willing to hear slander.

About whom [didn’t they want to hear slander]? About the baker who supplies hametz to Jews [on Passover]?! So according to [the Hafetz Hayyim’s] approach one does not need to discuss [this] and all the Jews should eat hametz, Heaven forbid?! This [type of dreadful] outcome is caused by the Hafetz Hayyim, because ignorant people apply his approach too strictly.

Shapotshnick then launched into an extraordinary personal attack on the Hafetz Hayyim, the likes of which was unprecedented in print, and indeed unique in as much as no one ever published such an attack on the Hafetz Hayyim, neither during his lifetime nor since his death.

Shapotshnick cited the Talmudic story of Rav Alexandri, who, based on a verse from Psalms,[44] guaranteed life to all those who refrained from speaking gossip and slander. Shapotshnick suggested a novel interpretation for the follow-up statement, in which the Talmud says that if someone were to say: “I have guarded my tongue from evil and my lips from speaking deceit” and therefore I have got nothing left to talk about, the Torah advises that person to “turn from evil and do good”, by which the Talmud means that the person should use his redundant mouth for “good”, namely the study of Torah.[45]

But Shapotshnick interpreted the passage slightly differently. In his distorted version, refraining from evil gossip and doing good means that a person’s redundant mouth could be used for good by engaging in talk that ensured the propagation of Torah, and the furtherance of Judaism, and if it was not used in this way, then the owner of that mouth was actually doing “evil” by saying nothing. In light of this inaccurate interpretation of the Talmudic homily, Shapotshnick impudently asked:

Why is the Hafetz Hayyim silent about the teaching of Bible criticism in schools in the Land of Israel? Why is he silent about so many issues? Why does he not stand side-by-side with those who seek the truth? The Hafetz Hayyim is an ish tam (“a gentle man”), yet he is noge’ah kemo mu’ad (“gores like a marauding ox”).[46]

Shapotshnick was trying to say that when good people say nothing, bad people get away with murder. But his mode of expressing this sentiment was utterly unacceptable, seeing as the Hafetz Hayyim was the object of this criticism. Then there was the irony that Shapotshnick was using an aggadic text to criticize the Hafetz Hayyim halakhically, which was the very crime he had accused the Hafetz Hayyim of being guilty of in his book.

But the biggest irony of all was that Shapotshnick had only found himself coming up with all of this because he had personally been the object of a public criticism by the Hafetz Hayyim, which meant that not only was he articulating himself inappropriately, and not only was he guilty of doing exactly the same thing that he had found wrong with the Hafetz Hayyim – but he had completely missed the point! Clearly the Jewish world’s primary promoter of careful speech had absolutely no problem using his mouth to denounce someone like Shapotshnick, nor did he feel when he was doing it that he was transgressing any of the laws he propagated by doing so.

RABBI HAYYIM OZER GRODZINSKI IS DESCRIBED AS A ‘ZAKEN MAMRE’

Shapotshnick’s attack against Rabbi Grodzinski, which followed immediately afterward his attack on the Hafetz Hayyim, was far worse. Without even giving him the title ‘rabbi’, he accused him of being a ‘sinner of Israel’. Clearly livid that Rabbi Grodzinski had disrespected him by not bothering to refute the reasons for his rulings in Likro la’asurim dror, choosing instead to condemn him personally, Shapotshnick suggested that his critic was ‘among those who disgraces Torah scholars,’ adding that if Rabbi Grodzinski had lived during the days when the Sanhedrin were in charge, he would have been declared a ‘zaken mamre’ (rebellious elder). The diatribe then descended into a bilious tirade:

Let me state clearly that if Chaim Ozer Grodzinski would touch wine, I would not drink the wine as it may have become yayin nesekh,[47] as anyone who does not accept the words of our sages, their wine [is not kosher]. Woe is to the city of Vilna that it has a rabbi who is not a rabbi who helps [people], rather is [instead] a rabbi who sins.[48]

If the attack on the Hafetz Hayyim was ill-advised, the attack on Rabbi Grodzinski was nothing short of professional suicide. There was no way a rabbi who operated in the strictly-Orthodox community could write so viciously against a man who commanded worldwide awe and respect in a newspaper directed towards and read by this very community, and then expect to be taken seriously by that same community.

Rabbi Grodzinski, who led Orthodoxy in a city and country that was at the center of Jewish life at that time, was recognized well beyond his region as an ultimate halakhic authority and was often the last word on political and social issues for communities on every continent. For all his knowledge and self-proclaimed pedigree, Shapotshnick was an obscure rabbi from London, a remote community in terms of Orthodox Jewish life, and was simply not in the same league as Rabbi Grodzinski. Even had the criticism of Rabbi Grodzinski been temperate and measured, it would still have been badly received. But the fact that Shapotshnick laced his criticism with insults meant that it would be automatically dismissed by everyone as the rantings of a foul-mouthed madman.

Shapotshnick also responded to the charges that the rabbis who had co-signed his rulings were minor and inconsequential, and their opinion did not count next to those of the Hafetz Hayyim or Rabbi Grodzinski by vigorously refuting this claim, and he went to great pains to prove that every rabbi who had co-signed for him was a rabbinic expert of the highest caliber.

One of the rabbis who endorsed [my rulings] is ten times greater than the Hafetz Hayyim. [This man] is a scholar who is not well-known to ignorant oafs, or repulsive reporters, only to genuine intellectuals, rabbis, righteous people and geniuses of our generation, and [the man] I am talking about [is] … R. Eleazar Sagal Mishel, chief rabbi of Turka.[49]

To show that Rabbi Mishel was as great as the late Rabbi Yitzchak Elhanan Spektor of Kovno, Shapotshnick reproduced a selection of superlative honorifics that had been used by rabbis who had approbated Rabbi Mishel’s published work, Mishnat Eleazar. But the idea that these honorifics were of any meaningful significance was totally ridiculous. Letters of approbation issued by rabbinic colleagues for insertion into a new book are often preceded by hyperbolic honorifics, and even when the most inflated terms are used, they do not mean that the recipient is one of the era’s leading rabbis. Claiming that Rabbi Mishel was ten times greater than the Hafetz Hayyim, or could be compared in prominence to Rabbi Spektor, demonstrated yet again that Shapotshnick was completely divorced from reality, and that Rabbi Hillman’s determination to bring him down was entirely justified.

Shapotshnick also reproduced the honorifics used in praise of several of the other rabbis whose names could be found as signatories on his rulings, in a further pointless attempt at using this method to prove that his supporters were world-renowned halakhic authorities whose signatures gave the dispensations credibility and clout. In truth, though, his opponents were right, as although many of the rabbis were no doubt great scholars, none of them had what it took to give these rulings the kind of authority that they needed in order to be taken seriously.

THE FINAL ACT IN THE SHAPOTSHNICK SAGA

Rabbi Grodzinski’s response to Rabbi Hillman’s letter in the wake of this offensive diatribe by Shapotshnick, if there was one, is not extant. But it is no coincidence that just over a week after Rabbi Hillman appealed to Rabbi Grodzinski for help, an article appeared in Die Tzeit that reported a ‘tremendous uproar’ in Warsaw regarding the ongoing controversy.

Quoting the Warsaw-based Yiddish tabloid Unzer Ekspress, Die Tzeit informed its readers that the Rabbinical Association of Poland had held an urgent meeting to discuss Shapotshnick’s misdeeds and had agreed on the text for a protest letter. Furthermore, the article reported the shock waves that had reverberated throughout the Jewish community in Poland when news had emerged of the letter of support sent to Shapotshnick by the Ostrovtza Rebbe. The elderly Hasidic leader was not someone who was easily dismissed, and his backing for Shapotshnick’s agunot activities gave them legitimacy, whatever his critics said.

According to the report, community leaders had traveled to Ostrowiec and arranged to meet with the ailing rabbi so that they could ask him why he was supporting Shapotshnick and his activities. They emerged from the meeting with the following statement explaining what had happened:

The London-based R. Shapotshnick recently approached the Ostrovza Rebbe to ask how he could improve Jewish religious life in London. The Ostrovtza Rebbe replied with the letter [later published by Shapotshnick]. The London rabbi then used the Ostrovtza Rebbe’s letter, which had been written about a totally different subject, to boost the campaign he is currently and energetically pursuing in relation to the agunot issue.[50]