ON THE BRINK OF UNCERTAINTY

(For the SoundCloud audio, scroll to the bottom of the page)

Charles Ticho of Hackensack NJ, who died last year at the age of 95, inadvertently had a hand in the founding of Israel’s movie industry. In 1954, he was invited to Israel to assist in the production of the first locally produced full-length feature film, “Hill 24 Does Not Answer” – which brought to life personal stories of Palmach soldiers on their way to defend a strategic hill near Jerusalem during Israel’s 1948 Independence War.

In 1955, after the movie was released, Ticho returned to the United States to try his hand at movie production. But aside from one feature film in 1960, “The Prime Time” – a risqué coming-of-age movie – Ticho’s primary focus shifted to directing commercials and industrial films. In his later years, he specialized in organizing conventions and conference programs for the film industry.

Despite his devotion to the movie industry, the true love of Charles Ticho’s life was his Jewish faith and his Jewish identity. He never forgot his roots – through his mother Fege, Ticho was descended from Rabbi Moshe Schick, the influential nineteenth-century rabbi of Chust, Hungary.

In particular, Ticho never forgot his family’s miraculous rescue from the jaws of Nazi genocide, a journey that involved the unexpected personal involvement of Italy’s fascist dictator, Benito Mussolini.

Ticho’s fascination with his roots saw him become an amateur genealogist, and he delved deeply into his family’s history, tracing it back to the late 1600s. He chronicled their stories, along with his own experiences, in two published works: “From Generation to Generation: A Family’s Story of Survival,” which came out in 2007; and “Stops Along the Way,” a collection of articles Ticho penned for the Jerusalem Post Magazine that appeared in 2022.

Ticho’s life began in Brno. After the First World War, Brno, the capital of Moravia, was part of Czechoslovakia, and home to a thriving textile industry. The Jewish presence in Brno dates back to the 13th century, although full Jewish residency in the city was forbidden until 1848.

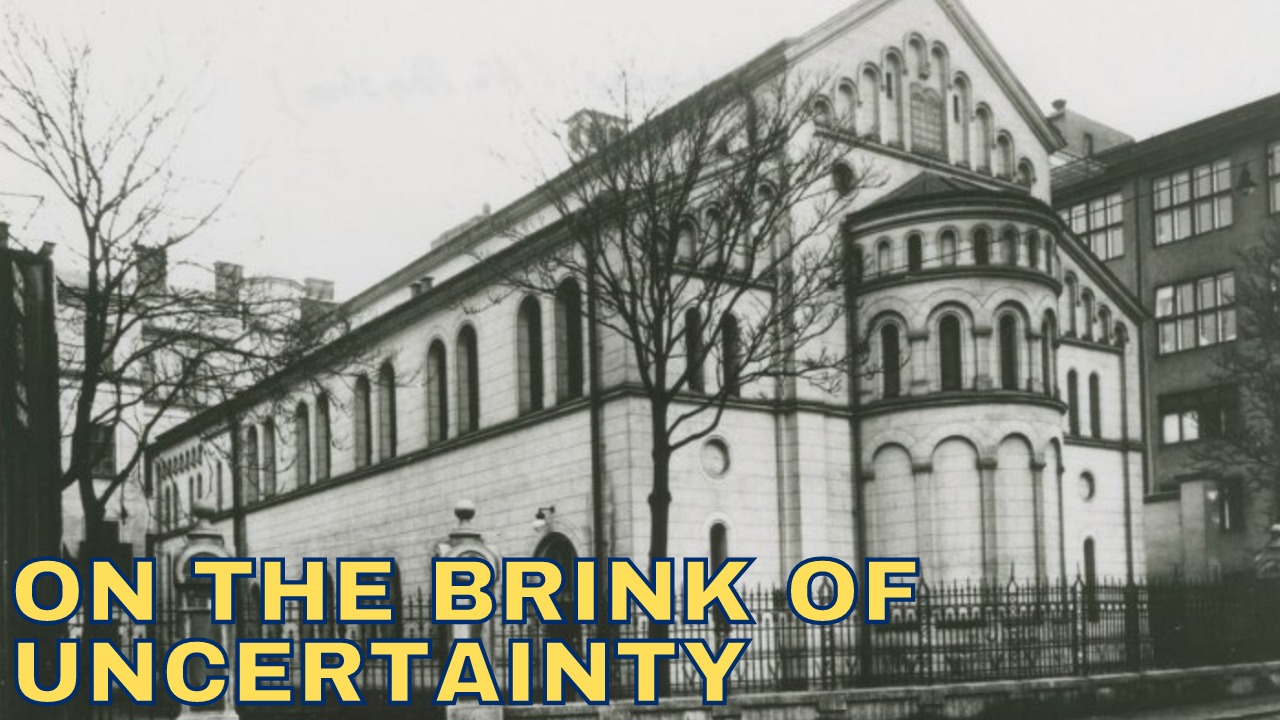

In March 1939, immediately after the Nazis marched into Bohemia and Moravia, they burned the main Brno synagogue to the ground with the cooperation of local fascists. The Jewish community in Brno then numbered just over 10,000 souls; most of them were murdered in the Holocaust.

In a touching article published in 2020, Ticho described Rosh Hashana in Brno in 1939, just a few months after the main synagogue was destroyed, and in the ominous shadow of Nazi occupation. He was just 12 years old.

“This was, by no means, just a usual Rosh Hashanah. There were many things unique even about this already very special holy day. It had been six months since the Germans invaded Czechoslovakia and many changes had taken place. For the moment, Jewish services were still permitted in two of our three synagogues. We did not know it at the time, but a few months later the doors to our “small temple” would be closed and locked, never ever again to hear the prayers of devoted Jews. After the war, it became a furniture warehouse and then it was torn down and a medical clinic replaced it. Today, only a small sign on a wall testifies where this grand synagogue once stood.”

“Other things made this evening unique. For the first time in my 12 years, my parents were not with me on this holiday. My father had been arrested by the Nazis and was being held in the Spielberg Prison in Brno. He would soon be sent to the Dachau concentration camp. My mother had departed for the United States about a year earlier in order to renew her American citizenship. On her return trip she reached as far as Zurich, Switzerland, where she remained. My older brother, Harold, was also no longer with us. He was now living in Chicago. My little brother and I were watched over by two elderly Uncles, Jacob and David.”

“One day in the future, in August 1940, little eight-year-old Steven and I would travel alone, through war-torn Europe to Switzerland and meet our mother after a two-year separation… [But right now,] there was so much tension all around. Things were so different from previous years, and throughout the services I became aware that this might just be my last Rosh Hashanah service in Brno. Regrettably, I was right… Little did I realize at that time, what horrendous challenges we would have to survive during the next five years. But survive we did.”

Charles Ticho and his family may have survived, but most of those with whom he prayed that year on Rosh Hashana did not. The mass deportation of Jews from Brno began on in November 1941, when 1,000 Jews were sent to Minsk ghetto. A further 2,000 were sent to Theresienstadt that December, and 7,000 more were deported to Auschwitz during the first few months of 1942, where the majority were either killed or died.

Brno’s vibrant community was decimated. The tragedy of this vibrant community did not end there. Efforts to revive the community after the war foundered, and today there are just 300 Jews in Brno, a fraction of the numbers that once formed this historic community at the heart of Europe.

The story of the Jewish community in Brno, and of Charles Ticho and his family is a story of persecution and displacement, and of severe trauma and cold-blooded murder. It has echoes in every location where Jews have ever lived, across the span of Jewish history.

Every Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur we refer to the uncertainty of our existence in an ancient prayer during which we pose the questions: “Who will live? Who will die? Who in their right time? Who before their time?” The prayer lists a range of gruesome deaths that might befall us, although, year after year, we imagine that we are immune to the dangers that are so vividly enumerated.

And yet, over the past few years, it has become ever clearer that the safety of our world is not only under threat, but that these threats are not somewhere yonder. The safety net of a stable democracy and protection from the extremes is no longer an ironclad guarantee.

I imagine that the Jews of Brno in the 1920s and 1930s, living in their own version of a democratic paradise, believed that no threat could upset their existence to the extent that the survival of their community was in doubt and their lives were in danger. By the time they woke up to reality, events had overtaken them.

The Talmud records the sage Rabbi Eliezer as saying, “Repent one day before your death.” His disciples were puzzled and queried his statement. “Does a person know on which day they will die?” they asked. To which he replied, “That being the case, let them repent today – for perhaps they will die tomorrow.” (Avot 2:10; Shabbat 153a).

In a world that often teeters on the brink of uncertainty, Charles Ticho’s final Rosh Hashana experience in Brno eerily dovetails with the stark words of our High Holidays prayer. They remind us to never forget the fragility of our existence, and to therefore use every day wisely – devoted to God and helping others – so that our fate, whatever it may be, is anticipated and mitigated to the maximum extent possible.

At the very least, may our awareness and our desire to do the best we can act as a blessing for us to be inscribed into the Book of Life.

Photo: The New Synagogue of Brno, where Charles Ticho prayed on Rosh Hashana in 1939. By kind permission from The Jewish Museum of Prague.