NOT QUALIFIED FOR LEADERSHIP

“The most dangerous leadership myth is that leaders are born — that there is a genetic factor to leadership. This myth asserts that people simply either have certain charismatic qualities or not. That’s nonsense; in fact, the opposite is true. Leaders are made rather than born.” — Warren Bennis

Warren Bennis wasn’t a rabbi or a theologian. He was one of the most influential leadership scholars of the twentieth century, advising presidents, studying institutions, and asking a deceptively simple question: where do real leaders actually come from?

His answer, distilled over decades, was that leadership is not a birthright and not a personality trait. It is forged — often painfully — by experience, failure, and distance from comfort.

When you read Parshat Shemot, it’s hard not to think that the Torah got there first. Because if you were asked to design the ideal leader to take the Jewish people out of Egypt, Moshe Rabbeinu would be a baffling choice.

In fact, everything we know about him seems to disqualify him from the job.

He doesn’t grow up among his people. He is rescued from the Nile and raised in Pharaoh’s palace, surrounded by privilege, power, and Egyptian culture.

He does not share the formative experience of slavery. He doesn’t sound like the people. He doesn’t live like them. If authenticity and shared suffering are prerequisites for leadership, Moshe looks like the wrong man.

Then comes his first recorded attempt at public action — and it goes terribly wrong. He kills an Egyptian. The next day, when he tries to intervene in a dispute between two Hebrews, he is rejected outright: “Who made you ruler and judge over us?” That’s not hesitation. That’s dismissal.

And then Moshe runs. He flees Egypt entirely and disappears for decades. No organizing. No leading. No movement-building. He becomes a shepherd in Midian, far away from his people and their pain.

So the question almost demands to be asked: why Moshe? If anything, the obvious candidate should have been his brother, Aaron. Aharon stays with the people. He lives among them. Chazal describe him as a peacemaker, someone who knows how to speak, how to listen, how to bring people together.

Later he becomes the Kohen Gadol. He is trusted, beloved, embedded. If leadership is about continuity, connection, and legitimacy, Aharon looks like the natural choice. And yet, God chooses Moshe. Why?

Because the Torah is teaching a counterintuitive and deeply uncomfortable truth: sometimes the very things that seem to disqualify a person from leadership are what ultimately qualify them.

Moshe’s distance is not a flaw. It is the point. He understands Egypt precisely because he no longer belongs to it. He has tasted privilege and walked away from it. He has failed publicly, fled ignominiously, and lived in obscurity.

He is no longer dazzled by power, nor dependent on it. And that is why the burning bush does not appear in Pharaoh’s palace.

It appears in the wilderness. Moshe had to leave Egypt to understand Egypt. He needed not to be a slave in order to understand how to free his people from slavery. What’s remarkable is that this insight isn’t just biblical theory. It was recognized, painfully and honestly, by Jewish leaders living through catastrophe themselves.

In a letter discovered only recently, the Yabloner Rebbe reflected to a friend about the demands that he replace his father as Rebbe after his passing in 1920. With striking self-awareness, he writes that he knew he did not fit the traditional Hasidic mold.

“After the passing of my revered father, may his memory be for a blessing, a great fear and trembling fell upon me. I was broken in spirit and weakened in body, and my heart was not at rest. I did not see myself as worthy or fit to take upon myself the burden that had rested upon him, for who am I, and what is my strength, to stand in the place of such a man?

In the letter, he says that when his father’s followers put pressure on him to take the job: “I resisted them with all my might. I spoke of my youth, my weakness, my lack of preparation. I said that I was not equal to the task, and that I feared Heaven’s judgment more than the judgment of man.”

He was different — he was not like other Rebbes in Poland, and he knew it.

In a 1977 interview, given George Nagel, his decades long alias when he lived in Los Angeles, he recalled that as a child he had a tutor who introduced him to Russian and French literature – hardly the type of material for a future Rebbe to be studying. In an era when authority was measured by insulation from modernity, this alone should have disqualified him.

And yet, history tells another, devastating story. When the clouds gathered over European Jewry, many rebbes — men far more “qualified” by traditional standards — chose to stay in Poland. They were – at least by standards that were understood at the time – older, wiser, more learned, more deeply rooted in inherited patterns of Hasidic life. They loved their communities and believed, sincerely, that remaining was an act of faith and responsibility.

And they kept their flocks in Poland and Hungary. And they, together with those flocks, were wiped out.

The Yabloner Rebbe did something different. Precisely because he was not fully captive to convention, precisely because he did not see himself as the natural embodiment of the old order, he urged his Hasidim to leave and join him as a pioneer in pre-state Israel. He broke with instinct, with precedent, and with expectation.

Years later, after his own exile, survivors told him something extraordinary: it was because you were different that we survived. He thought his difference disqualified him. It turned out to be the very thing that saved lives.

And suddenly, Moshe looks very different. Moshe isn’t chosen by God despite being an outsider. He’s chosen because of it. Aharon is indispensable — but in a different role. He is the bridge to the people, the voice, the heart. Moshe is the one who can stand before Pharaoh and say “Let my people Go!” — because neither Egypt nor anyone owns him.

Warren Bennis was right. Leaders are not necessarily the product of convention. Often it is because they are unconventional that they can be so successful.

Moshe thought his background was a liability. The Yabloner Rebbe thought his difference was a weakness. The Torah — and history — tell us otherwise. Because when systems are breaking, continuity alone is not enough. Sometimes salvation comes from those who love their people deeply enough to step outside the mold — and act differently, before it’s too late.

So perhaps the question Parshat Shemot leaves us with is not only why Moshe, but whom we look for when we need leadership. Do we instinctively gravitate toward those who fit the mold, who speak the right language, follow the rules flawlessly, and reassure us with continuity? Or do we make room for leaders who think differently, who are willing to challenge convention, who see dangers and possibilities others miss precisely because they stand slightly apart?

And the question doesn’t stop with leadership selection — it turns uncomfortably inward. When faced with moral or communal failure, is it safer to be the insider who follows the rules to the letter, or the outsider willing to disrupt, to question, to act?

The Torah’s answer is bracing: history is not moved forward by those who fit perfectly, but by those who refuse to be owned by the system. Sometimes, the holiest thing a person can do is stop fitting in — and start shaking things up.

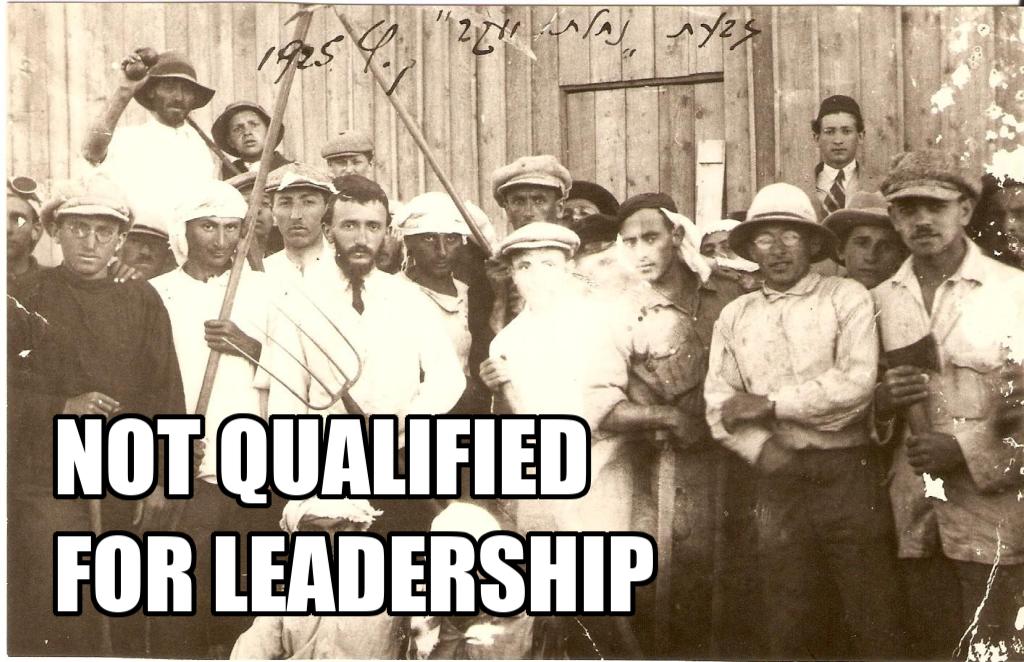

Photo: The Yabloner Rebbe, Rabbi Yechezkel Taub, together with his followers from Poland, in Kfar Hasidim, Northern Israel, in 1925.