MY FOND MEMORIES OF MORDECHAI “PUPIK” ARNON

I was 8 years old when I met him for the first time; truthfully, he was the first real “showbiz” star I ever encountered.

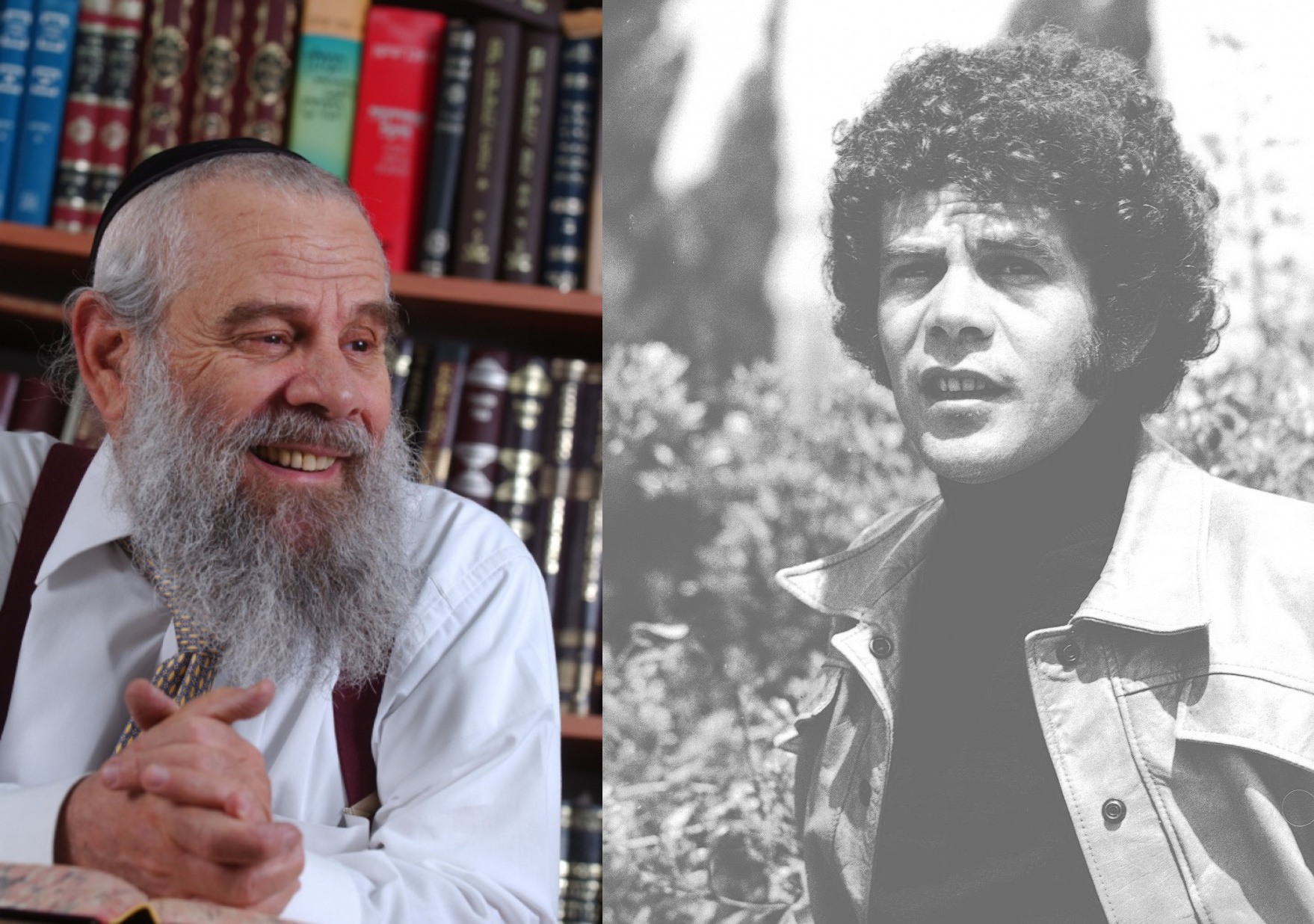

In his heyday, Mordechai “Pupik” Arnon – who died last week aged 78 after a difficult battle with cancer – was one of Israel’s most beloved stars. His moment in the spotlight was during the 1960s and 1970s, when Israel was experiencing its major post-independence explosion of art, film, music, and literature.

Pupik is Yiddish for navel, a nickname Arnon picked up because of his diminutive size, but although he was physically tiny, he was always the biggest personality in the room. He was a singer and an actor, but more than anything else Pupik was absolutely hilarious, a first-class comedian in whose mouth every story was funny, and every punchline was perfect.

His close friends included Chaim Topol, with whom he costarred in the 1964 Israeli movie Sallah Shabbati, a whimsical social satire about Jewish immigrants directed by Ephraim Kishon and produced by Menachem Golan – all of them at the very beginning of careers that would propel them to international fame and celebrity.

During the Yom Kippur War of 1973, Pupik performed for Israel’s beleaguered troops alongside the legendary Canadian singer Leonard Cohen – the soldiers had never heard of Cohen, and were apparently more eager to watch Pupik perform.

He was truly a rising star, with a bright future ahead of him. Hollywood and Broadway beckoned, nevertheless Pupik chose a different path, one that meant he would completely disappear from the public eye, despite his extraordinary talent and prodigious energy.

Pupik grew up completely secular and had no social contact with religious Jews whatsoever. Then, in 1975, at the height of his success, he suddenly began to feel that his life was devoid of meaning – or as he put it: “I needed to find out why I existed.”

In desperation, he struck up a conversation with a group of religious Jews in Jerusalem, mainly to prove to himself that religion had nothing to offer that would enhance his life.

“I asked them many difficult questions,” he later told Maariv newspaper, “but they asked me even more difficult questions – questions that I could not answer. It was then that I realized I needed to examine my life more deeply. I tried many philosophies and ideas to answer my questions but realized that if I did not also examine Judaism seriously, I might end up living a lie.”

Within a few months Pupik dropped out of public sight and went to study at Ohr Someach yeshiva in Jerusalem. When he reemerged, he was a fully committed orthodox Jew, a commitment he fervently maintained for the remainder of his life.

Such was the impact of his startling metamorphosis, that several of his high-profile friends followed in his footsteps and also became religious – most notably the renowned actor and director Uri Zohar, and the celebrated artist Ika Israeli.

Having rejected his showbiz career, Pupik moved from Tel Aviv to the religious Shaarei Hesed neighborhood in Jerusalem, where he became a familiar fixture at the GR”A Synagogue. He devoted the rest of his life to raising an orthodox family, and to creating religious education programs for secular Israelis, often involving clever movie shorts and various other unusual gimmicks.

My family got to know Pupik after he randomly knocked at the door of my parents’ home during the Shavuot of 1978. I don’t recall the reason he suddenly turned up out of the blue; all I can remember is that he had us all in stitches with his spontaneous sketches and riotous routines.

Thereafter he came every year, often together with Ika Israeli, occasionally with Uri Zohar – and I can even recall a fundraising event at my parents’ home with Chaim Topol. The money Pupik raised all went to fund his groundbreaking educational projects.

Even as a fundraiser Pupik was original and creative. On one occasion a philanthropist was playing hard-to-get and not returning Pupik’s calls, so he went to a passport photo booth and took dozens of photos of himself making different faces, stuck them to sheets of paper and faxed them to the philanthropist with a note saying “I am trying to reach you – these photos are just in case you’ve forgotten what I look like.” It was so unique – classic Pupik.

The portion of Vayechi records the death of Jacob, or at least so it seems. At first we are told that he is old and sick; Jacob then tells Joseph he is going to die; soon afterward Jacob gathers his sons together for a final deathbed meeting and he blesses them; and finally Joseph and his brothers “saw that their father had died” and take him to be buried in Hebron, the last person to be interred in the Cave of Machpelah.

But there is a problem with that narrative – the Torah never actually informs us that Jacob has died, instead telling us (Gen. 49:33): וַיֶאֱסֹף רַגְלָיו אֶל הַמִטָה וַיִגְוַע וַיֵאָסֶף אֶל עַמָיו – “he drew his feet into the bed, he expired, and he was gathered to his people.”

There is no direct mention of his death using the standard Hebrew word ‘vayamat’, and it is this anomaly that prompts the Midrash to say: “our forefather Jacob did not die”. But this is quite a curious statement, bearing in mind that we later read of Jacob being buried.

Jacob is seen as the founding father of the Jewish nation. His alternative name, Israel, would later become synonymous with the nation that emerged from his descendants.

Although his father Isaac and grandfather Abraham had a part in the foundation of Jewish nationhood, they also fathered other nations through their other children. But while these nations may have existed for centuries, their collective rejection of God rendered them lifeless even as they thrived, and part of Abraham and Isaac died with them.

Jacob’s descendants, on the other hand, by being the standard-bearers of God’s mission and of God-belief in a world that rejects God, ensured that Jacob remained alive even though he was physically gone.

My friend Pupik made a remarkable life choice at the pinnacle of his career. Fame and fortune are ephemeral, he decided, a flash-in-the-pan that will not ensure eternal life.

And so he abandoned his certain path to a life of stardom, and instead chose to be like Jacob – a choice to live on even after he had died, through a legacy of commitment to Judaism and a Jewish future that will long outlive his tiny physical presence on this earth.