MARK TWAIN VISITS THE HOLY LAND

In 1867, a young man called Samuel Langhorne Clemens set sail from New York, bound for Europe, Africa, and the Middle East.

Clemens is better known by his pen name, Mark Twain, although in 1867 he was still an obscure journalist who had somehow convinced a California newspaper to fund this spectacular trip abroad, in exchange for regular updates from different stops on his journey.

Twain’s two most famous books, Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, were still many years away, and much rested on the success of his travelogue. As it turned out, the five-month cruise was a gamechanger, and the resulting book, The Innocents Abroad (1869), sold 70,000 copies in its first year, and was Twain’s bestselling book during his lifetime.

Twain carefully constructed his reports to reflect the reactions of an average layperson visiting exotic lands far away from home, and specifically a person who would not allow preconceptions and mythology to overwhelm the reality of what he saw.

The result was refreshing, and highly unusual for the nineteenth century.

Lake Como in Italy was nice, Twain said, but Lake Tahoe back home in the United States, was nicer. Mount Vesuvius was unimpressive when compared to the Kilauea volcano in Hawaii. Although Twain was enthralled by the grandeur of Milan, Venice, Florence and Rome, he was disgusted by the vast economic gap between rich and poor in Italy, particularly as it was evident that all available resources had been invested in architecture and edifices, instead of the impoverished population.

The most important leg of the journey for Twain and his fellow passengers was their visit to the Holy Land, then known as Palestine, at the time a minor outpost within the Syrian province of the Ottoman Empire.

Most of the tourists on Twain’s trip were devout Christians on their first pilgrimage to the land of the bible, and Twain, who was brought up Presbyterian, was undoubtedly swept up by the excitement and anticipation of reaching the Promised Land, spurred on by his distaste for almost everywhere else he had visited along the way.

But just about every myth and expectation was dashed by the reality Twain confronted when he arrived.

“The word Palestine always brought to my mind a vague suggestion of a country as large as the United States,” he began, “I do not know why, but such was the case. I suppose it was because I could not conceive of a small country having so large a history.”

Unlike the grandiose palaces and churches Twain had encountered in Europe, along with the teeming cities and towns of Turkey and Syria, the land of the bible was not just a jarring contrast, it was inconceivable in light of the rich history with which it was associated. Western civilization owed itself to countless centuries of events that had occurred in this exact geographic location, and yet it was a veritable wasteland, whose inhabitants – of all faiths and cultures – were primitive and unsophisticated.

“Palestine sits in sackcloth and ashes. Over it broods the spell of a curse that has withered its fields and fettered its energies.”

Twain described in vivid, unfiltered detail, the squalor and desolation he witnessed in every place he visited across the country, and his description of Jerusalem, once the crown of Judea, is particularly disturbing.

“Renowned Jerusalem itself, the stateliest name in history, has lost all its ancient grandeur, and [has] become a pauper village; the riches of Solomon are no longer there to compel the admiration of visiting Oriental queens; the wonderful temple which was the pride and the glory of Israel, is gone.”

The state of Jerusalem’s inhabitants only underscored just how much this once glorious city had sunk into decline.

“It seems to me that all the races and colors and tongues of the earth must be represented among the fourteen thousand souls that dwell in Jerusalem. Rags, wretchedness, poverty and dirt… abound.”

Twain was particularly struck by how barren the country was, and how few people there were. As he traveled through the Jezreel Valley, he noted “there is not a solitary village throughout its whole extent – not for thirty miles in either direction…. [and] one may ride ten miles hereabouts and not see ten human beings.”

With hindsight, this was hardly surprising. The population of Palestine in the 1860s was 350,000; compare that to today’s 8.5 million.

Twain’s conclusion was that the Land of Israel was a bitter disappointment. It is “desolate and unlovely,” he wrote, although “why should it be otherwise? Can the curse of the Deity beautify a land? Palestine is no more of this work-day world. It is sacred [only] to poetry and tradition; it is dream-land.”

Twain’s final analysis was that the Holy Land was a fantasy for religious dreamers looking for ghosts in a cemetery that was trapped in eternal damnation.

But how wrong he was.

Approximately 2,600 years ago, the prophet Ezekiel prophesized (Ez. 36:8): וְאַתֶּם הָרֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל עַנְפְּכֶם תִּתֵּנוּ וּפֶרְיְכֶם תִּשְׂאוּ לְעַמִּי יִשְׂרָאֵל כִּי קֵרְבוּ לָבוֹא – “But you, mountains of Israel, will produce branches and fruit for my people Israel, for they will soon come home.”

According to the Talmud (Sanhedrin 98a) “there is no greater sign of the redemption than [the fulfillment of] this [verse].”

The Holocaust martyr, Rabbi Yissachar Shlomo Teichtal, in his seminal work Eim Habanim Semeicha, writes that the desolation of the Land of Israel, as described by Twain, is an essential component of that prophecy, a precursor to the flourishing renewal of the land in Messianic times.

Seventy years after the creation of the State of Israel, we have all personally witnessed the fulfilment of that prophecy, and as we contrast the highly developed, prosperous country with the dreadful place described by Mark Twain, and even with the struggling Israel that marked most of its formative years, let us all be acutely aware that the fulfilment of Ezekiel’s prophecy was highlighted by the Talmud as the greatest sign of imminent Messianic redemption.

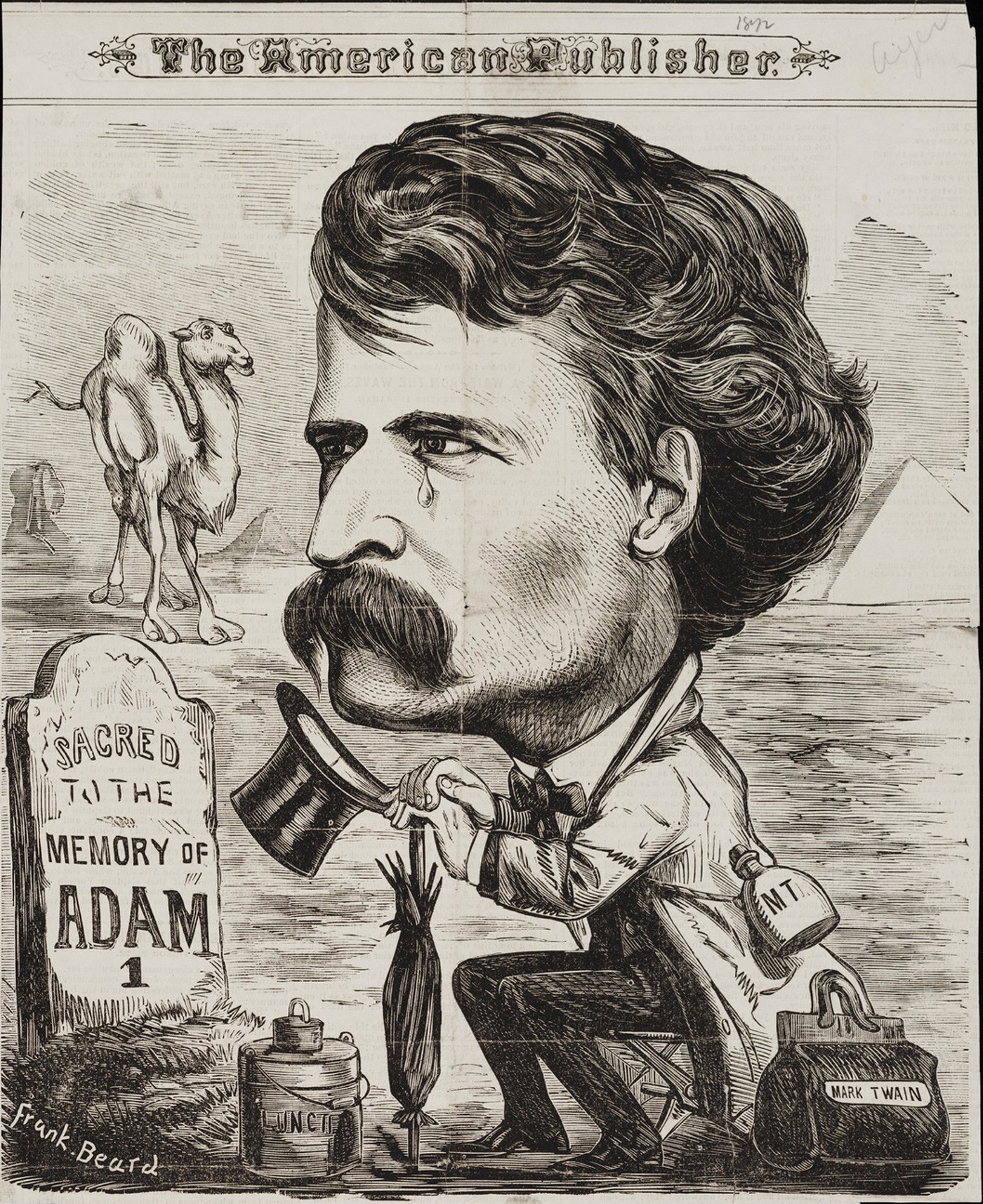

Photo: Mark Twain, “Sacred to the Memory of Adam”, cartoon based on an episode in The Innocents Abroad, published in The American Publisher vol. 3 (1872)