MAKERS OF HISTORY WHO ARE MADE BY HISTORY

This week saw the launch of my debut book, “Mavericks, Mystics & False Messiahs”, marking the end of a long and enjoyable literary journey.

Late last year, when I was putting the final touches to the book, I decided to add quotes before each section, in an effort to capture the essence of what followed.

For the book’s introduction I chose two quotes. The first is from Harry Truman, whose lifelong love of history originally stemmed from his having been excluded from sports activities as a child, due to his poor eyesight, which ironically resulted in his obsession with reading, particularly history books.

The quote I chose – “There is nothing new in the world except the history you do not know” – uses a clever play on words to deliver a powerful message about the relationship of the present with the past. Truman’s quote skillfully conveys the idea that concepts and events which appear novel and unusual in the present have generally played themselves out numerous times in the past, and the only reason they seem original is due to the ignorance of the observer.

The French have a saying for this: plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose – “the more it changes, the more it’s just the same thing.” Each successive generation wants to believe that they have an advantageous edge over previous generations. But those who know history see things quite differently.

As the charming Yiddish comedian Shimon Dzigan once quipped, “the only thing new in this morning’s newspaper is the date.”

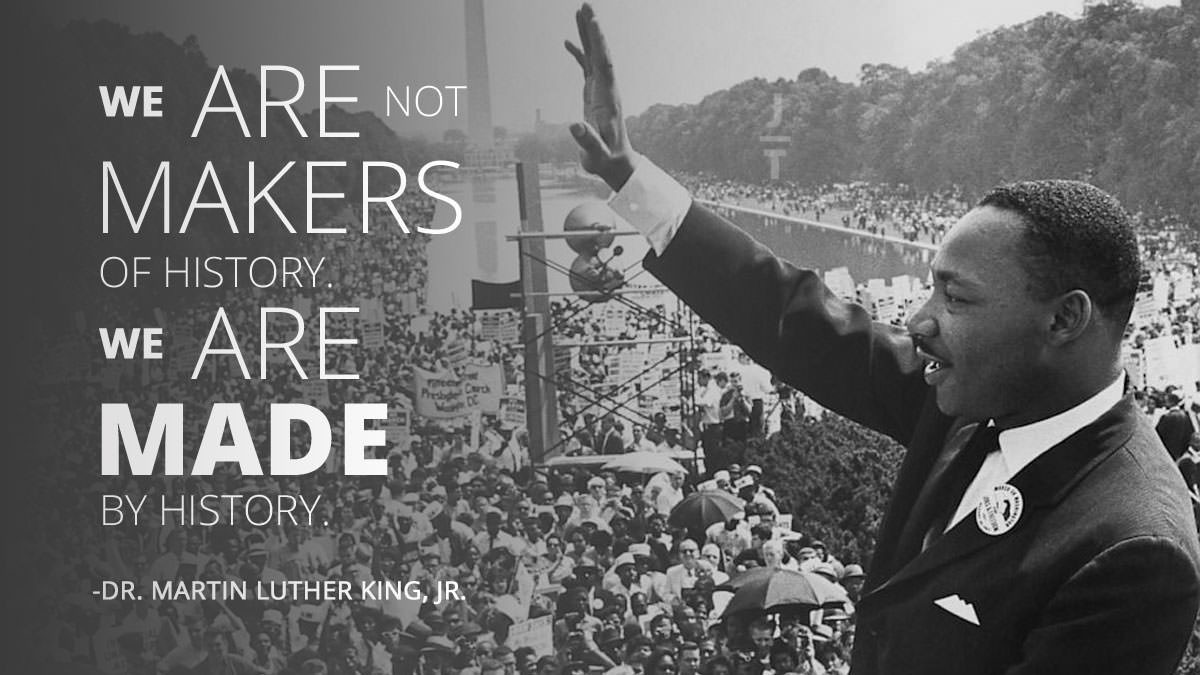

My second introductory quote is from Martin Luther King Jr. “We are not makers of history, we are made by history,” he told his congregation in 1954 – a declaration that went on to become one of his best-known lines.

Usually understood to mean that humanity is subject to the forces of history whether we like it or not, and that the winds of change will sweep away those attempting to shape history to fit in with their warped worldview, in reality King was reproaching his flock for not being more proactive in their battle for civil rights. Never allow yourself to become a victim of history, he was telling them – we are only “made” by history if we allow ourselves to believe that we are helpless to change its trajectory.

But I prefer a third interpretation – neither the way this quote is generally understood, nor the way King actually meant it. Rather, we are only makers of history as a result of being made by history – in other words, we are neither original, nor predetermined.

Those who attempt to forge an original path, ignoring the direction of history which led them to the present, will surely be frustrated in their efforts, which will be inevitably short-lived and abortive. And those who refuse to be proactive in the present in the mistaken assumption that no effort will alter their predestined path, will have abandoned their responsibility and missed their own unique opportunity to contribute to history.

At the beginning of Parshat Toldot, we are introduced to the sad predicament of Isaac and Rebecca, who remained childless after several years of marriage. The bereft couple pray fervently for a reversal of fortune (Gen. 25:21): וַיֶעְתַּר יִצְחָק לַה’ לְנֹכַח אִשְתּוֹ … וַיֵעָתֶר לוֹ ה’ וַתַּהַר רִבְקָה אִשְתּוֹ – “Isaac pleaded with God on behalf of his wife… and God responded to his plea, and his wife Rebecca conceived.”

In the previous verse, before informing us of Isaac’s prayer, the Torah had reminded us that Rebecca was the daughter of Bethuel and the sister of Laban – seemingly superfluous information as we are already fully aware of her family dynamics.

According to Rashi the Torah only mentions Rebecca’s iniquitous father and brother in order to praise Rebecca, who was brought up in their home and was nonetheless a righteous woman. And yet, just one verse later we are informed that it was Isaac’s prayer that was answered by God, not Rebecca’s, and the very same Rashi informs us that this was due to her poor lineage as compared to Isaac’s illustrious parentage.

Rabbi Moshe Teitelbaum of Ujhely, author of the Yismach Moshe commentary, has a radical interpretation of the words “l’nochach ishto” in the verse, which he suggests means “on the basis of his wife’s merits.”

Isaac had always seen himself as living in the shadow of his father. He believed himself to have been made by history (Gen. 25:19): “These are the generations of Isaac son of Abraham; Abraham begot Isaac.”

Meanwhile Rebecca was a maker of history; she had forged a new path for herself, different from that of her family, Bethuel and Laban.

Isaac was certain that Rebecca had a distinct advantage over him, as she had overcome the potentially crippling weakness in her background to become who she was. He therefore prayed to God “l’nochach ishto” – on the basis of her merits, and to the exclusion of his own, which he reckoned were utterly inadequate by comparison.

But God’s response is very revealing. Rather than responding to Isaac as the son of Abraham, he responded to Isaac as himself – “va’yetar lo.” With this powerful statement God acknowledged Isaac’s own originality even as he closely emulated his father.

The Torah’s lesson is that Isaac was a maker of history who had been made by history. Rather than merely acting out an empty echo of his father’s life, he had been able to forge his own path despite the weight of history, no less of a feat than that of his wife.

And particularly when it pertained to prayers for children, God wished to convey the importance of family precedent, as well as the importance of forging one’s own independent path in the shadow of that very same family precedent, keeping the traditional path fresh and dynamic, neither abandoning it nor submitting to it.

And although that may not have been what Martin Luther King Jr. actually meant in 1954, it certainly makes much more sense.