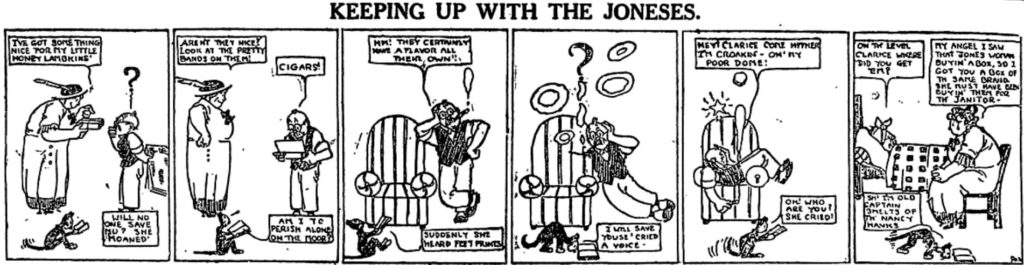

KEEPING UP WITH THE JONESES

On November 10, 1987, artist Arthur R. Momand died in New York at the age of 100 years old.

Although a short obituary appeared in the New York Times, his passing went largely unnoticed. Truthfully, this is hardly surprising, as even in his heyday he was hardly a household name – and his heyday ended almost 50 years before he died.

Nevertheless, Momand ought to be celebrated for having made an indelible mark on both the English language and popular culture as the originator of the idiom “keeping up with the Joneses”.

Fondly referred to as “Pop”, Momand was a strip-comic artist originally hired by the New York World in 1905. A talented satirist, he succeeded in producing a number of popular strip-cartoons which were syndicated across the country.

After his marriage in 1910, and flushed by his moderate success, Momand moved from New York City to Cedarhurst in Nassau County, where he soon found himself struggling to make ends meet as he attempted to stay materially on-par with his neighbors. As he later admitted, “we were living far beyond our means in our endeavor to keep up with the well-to-do class”.

By 1912 he had given up the fight and moved back to Manhattan, where he and his wife lived in a cheap rented apartment.

Momand was so affected by his encounter with the social-climbing fast-lane, it inspired him to launch a comic-strip to share his experiences. Originally conceived as “Keeping Up with the Smiths”, the strip ended up being called “Keeping Up with the Joneses” and ran weekly from 1913 until 1938, charting the life of the fictional

The comic’s main focus was the family’s endless efforts to “keep up” with the lifestyle of their neighbors, the never-seen but often-mentioned Jones family.

The public loved it, and “keeping up with the Joneses” entered English vernacular, where it remained long after the cartoon was forgotten. The phrase is still used, describing those who compulsively engage in social competition.

The Hungarian game theory pioneer John Harsanyi,

More notably he added that “this concern for social status is perhaps more conspicuous in those societies, like the American, where the ruling ideology encourages a striving for upward social mobility, for movement to higher social status positions.”

The sages of the Talmud were rather more direct, pithily observing (Kohelet Rabba 1:13) that: “he who has one hundred will want two hundred, and he who has two hundred will want four hundred.” The commentaries add that even when one hundred is enough, those who need to keep up with the Joneses will never be satisfied if others around them have two hundred.

The Torah portion Metsorah records the purification process for a person afflicted by

Tsara’at was a disease afflicting those who engaged in slanderous gossip and it resulted in an enforced period of quarantine. After seven days of isolation, the priest would sacrifice a guilt-offering on the person’s behalf and then wipe some of the blood on his or her right ear, thumb and big toe, as part of the rehabilitation process.

This unusual ritual has just one parallel in Jewish law—the inauguration of a new priest into active service.

But why would a process marking the elevation of a priest, Judaism’s most auspicious religious position, be echoed for an individual who has been ousted from society as a result of their antisocial behavior?

The Talmud (Sotah 9a) records the sin of the primordial serpent in the Garden of

But because the serpent “placed his eyes on that which was unfit for him, and desired that which was not given to him, what was in his possession was taken away from him.”

The serpent is often used as a symbol of slanderous gossip; here it is told by God that it would never enjoy its food, an idea seen as a metaphor for the uselessness of slander as a tool for personal growth.

According to the Talmud (Bava Batra 165a), only a minority of people stumble into a life of wanton immorality, although the same cannot be said about theft. However, no one – not one person – is immune to the temptation of lashon hara.

This curious observation flies in the face of any rational understanding. Humans are primarily motivated by gratification, hence the fatal attraction of promiscuity and theft. But why would anyone be attracted to petty gossip if there is no material benefit?

It seems that our Talmudic sages understood human psychology only too well. Every person craves

But “keeping up with the Joneses” is a slippery slope. Instead of developing our inner potential we forge a path based on the success of others. Worst of all, we might resort to pushing others down so that we can rise above them. But rather than feeling accomplished, success in the rat race only results in us feeling vacant and needy – we may have one hundred, but we end up wanting two.

Our desire for self-worth results in lashon hara, in the mistaken belief that denigrating others will somehow elevate us. But lashon hara is a compulsion that drives us off our beaten track, diminishing our self-worth rather than building it up.

The ordained priest of ancient Judaism was meant to embody the pinnacle of spiritual achievement, and the ordination ceremony confirmed that he was an outstanding individual. Using the very same ritual for those emerging from

Rather than keeping up with the Joneses, you could just be yourself.

With grateful thanks to Rabbi Yochanan Zweig of Miami.