IT’S ALL ABOUT THE RELATIONSHIP

Every year, for one full 25-hour day, Jews across the world reflect and pray. That day is called Yom Kippur.

On Yom Kippur, one’s fate for the coming year is sealed, and as part of our deference to the seriousness of this auspicious day, the Torah requires that we fast.

But Judaism, being the very practical religion that it is, prohibits us from fasting if doing so endangers life.

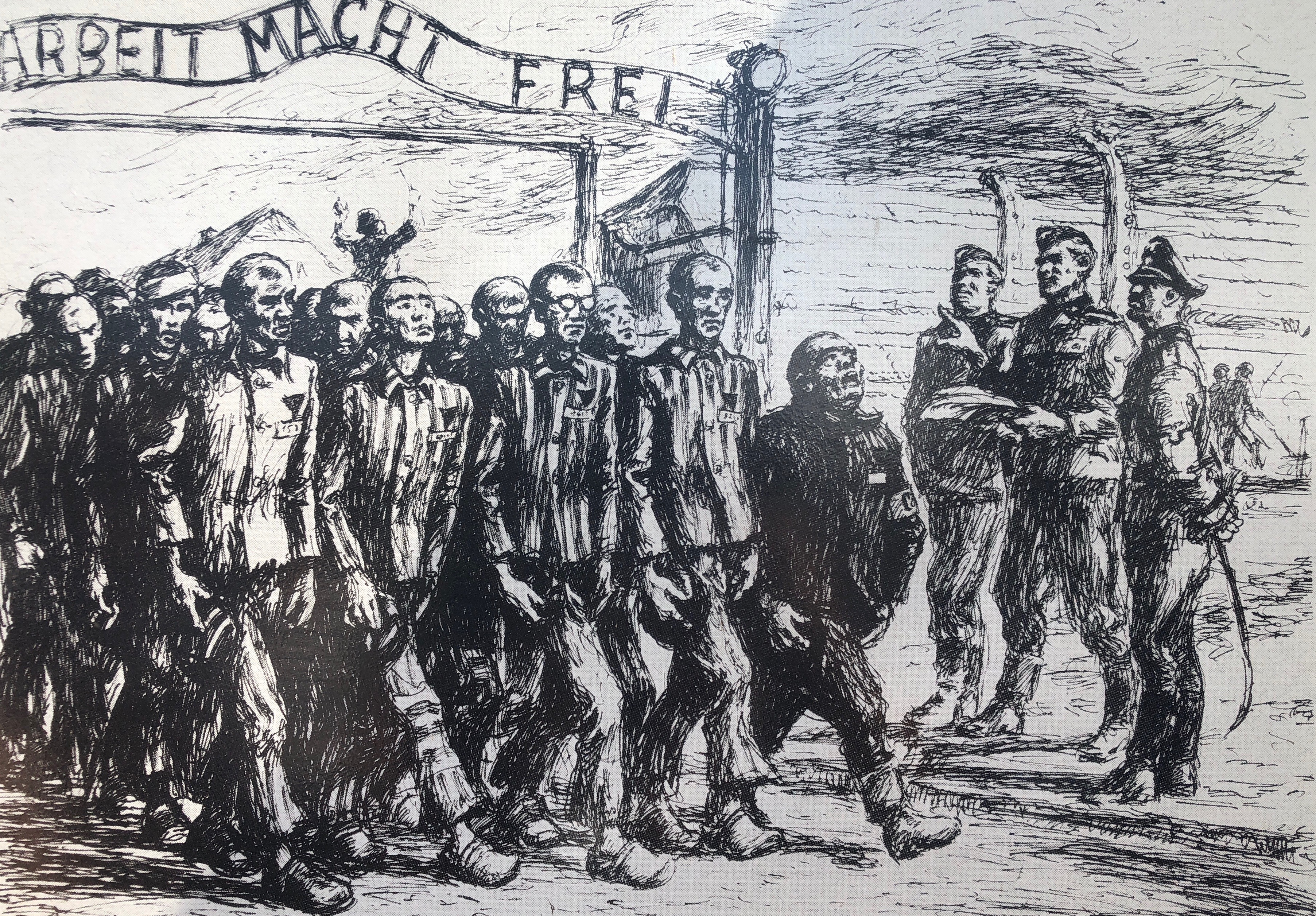

Seventy-five years ago, as Yom Kippur approached, the Jewish inmates of Auschwitz-Birkenau debated whether or not to fast. They were, after all, starving — each of them hovering close to death.

Among the inmates was a teenager called Elie Wiesel, just three days shy of his 16th birthday. He would later write of the debate he witnessed that day in Auschwitz.

“The question was hotly debated … in this place, we were always fasting — it was Yom Kippur all year round. But there were those who said we should fast anyway, precisely because it was so dangerous to do so. They said that we needed to show God that even here, locked up in hell, we were capable of singing His praises.”

What I find most striking about this passage by Wiesel is the purity of faith that it communicates — starving men debating about fasting on Yom Kippur as if their life or death depended on the outcome of the discussion, while in real life they were dying from starvation in the pit of Hell.

Wiesel tells us that he did not fast that Yom Kippur. In part, this was because his father forbade him from doing so.

But there was another reason, as he later recalled. He ate on that Yom Kippur as “a symbol of rebellion, of protest against God.” For the young teenager, eating that Yom Kippur was not an act of denial, rather it was an act of faith.

Ultimately, Yom Kippur demands of us that we engage in a relationship with God. The greatest threat to our existence as Jews is if we abandon God and deny His existence. Our purpose, our mission, is to include God in our lives and to nurture our relationship with Him, making it meaningful in every situation, good and bad.

With God at our