INTELLIGENT EVOLUTION AND THE ORAL TORAH

One of the great puzzles of evolutionary theory concerns the existence in humans of higher intelligence, and an innate desire for morality and ethics.

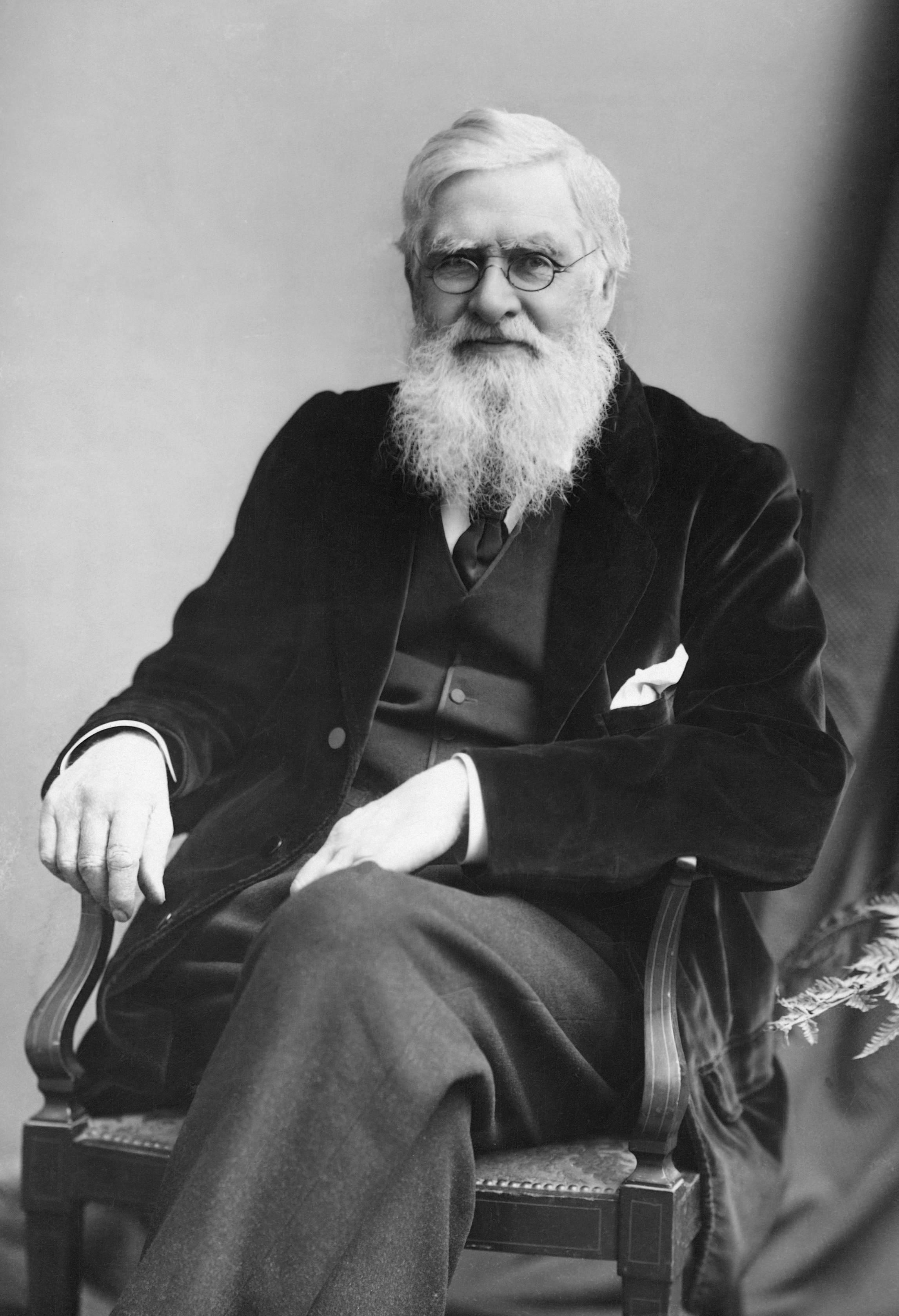

Charles Darwin (1809-1882) was compelled to publish a lengthy riposte to Alfred Wallace (1823-1913), his close collaborator and the celebrated co-proponent of his theory of natural selection, after Wallace advocated that evolution could not satisfactorily explain certain aspects of human development, which, among other things (such as hairless backs), included advanced intellect and moral instinct.

According to Wallace, “those faculties which enable us to transcend time and space, and to realize the wonderful conceptions of mathematics and philosophy, or which give us an intense yearning for abstract truth… are evidently essential to the perfect development of man as a spiritual being, but are utterly inconceivable as having been produced through the action of a law which looks only, and can look only, to the immediate material welfare of the individual or the race.”

Elsewhere he wrote, “let us not shut our eyes to the evidence that an Overruling Intelligence has watched over the action of those laws, so directing variations and so determining their accumulation, as finally to produce an organization sufficiently perfect to admit of, and even to aid in, the indefinite advancement of our mental and moral nature.”

Darwin was horrified, and immediately set about publishing his thoughts on the evolution of the human race, a subject he had deliberately omitted from On the Origin of Species, his 1859 magnum opus.

The result was The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex, which proposed, among other things, that morality is nothing more than an advanced form of social instinct rooted in our biological drive to survive.

Taken to its ultimate conclusion, this idea is very disturbing, to say the least. After all, if an alternative instinctively guided method can better guarantee the enduring existence of advanced humanity – such as a proactive eugenics program, or meticulously planned genocide – morality can surely be discarded in its favor.

Unsurprisingly, Darwin’s earliest acolytes went on to become the leading proponents of eugenics, including several members of his own family – his two sons, George and Leonard, led a eugenics organization in England, while his cousin, Sir Francis Galton (1822-1911), became the founder of the horrifically named “eugenics crusade”, a program that foreshadowed the Nazi obsession with eugenics, and the Holocaust.

But let me return to Wallace, and his belief that a conscience cannot be adequately explained using the theory of natural selection.

Even though he was feted during his lifetime, Wallace was dismissed by many fellow scientists as a spiritualist crank, and successfully marginalized by Darwinist purists, to the extent that he never entered popular consciousness, and most people have never heard him.

Considering that he never abandoned the concept of evolution, and certainly had nothing in common with ardent religious creationists of his era, such as Darwin’s most prominent critic, the pugnacious Bishop of Oxford, Samuel Wilberforce (1805-1873), how he reconciled scientific rationalism with his religious beliefs is both revealing and intriguing.

In recent years, the term “Intelligent Evolution” has emerged to describe a symbiotic partnership between natural selection and divine design.

Echoing the ideas first suggested by Wallace, Intelligent Evolution does not entirely dismiss Darwin’s principle of utility, namely that aspects of an organism will only develop if they give the organism a survival advantage.

Nevertheless, when dealing with elements of human physiology and intellect that present a challenge to the utility principle, Intelligent Evolution proposes that these advantages are the result of divine design, in place to be activated when required.

While this proposition is more complex than my short article could do adequate justice, it offers a glorious explanation for the theological conundrum posed by the biblical book of Deuteronomy. This book, the fifth volume of the Pentateuch, is stylistically distinctive from the rest of the Torah, in that it records the words of Moses, as opposed to the word of God.

Despite this startling difference, Deuteronomy shares equal status with the preceding four books, unlike those other books in the Hebrew Scriptures that record the words of a prophet, such as Isaiah, or Jeremiah.

Some of the commentaries are of the view that elevating Moses’ discourses to this supreme status was God’s ultimate gift to His most trusted servant, the man who brought the Jews out of Egypt, and who was God’s personal agent when they received the Torah.

But while this is a wonderful idea, it does not accord with the section in Va’etchanan (Deut. 5:1-22) that records Moses’ repetition of the Ten Commandments, first uttered by God at Sinai (Ex. 20:1-14). Had this section been a verbatim duplication, it would be fine. But it isn’t, and differs from the original in numerous places.

The medieval commentator, Abraham Ibn Ezra (1089-1167), devotes detailed attention to this anomaly in his longest single piece of Torah commentary, and concludes that Moses’ version of the Decalogue contained explanatory changes and additions.

Later commentaries augment this idea by proposing that the move from God’s word to Moses speaking introduces us to the concept of Oral Torah, which utilizes the Pentateuch as the foundation of a dynamic God-oriented system to govern society, and to maintain moral standards.

The idea of an evolving system that uses the raw words of Torah as its basis appears to be the theological parallel of Intelligent Evolution. Just as human beings have capacities and qualities that in early history exceeded our needs, but which were divinely placed there to be utilized when the need arose, the Torah contains information that was not evident to those who first encountered it, or perhaps, as Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch suggests, not yet relevant, but which was embedded there for future use.

Which is why it was so important that an augmented and embellished version of the Ten Commandments had to appear as part of the Torah, to establish this principle as an integral part of our theological system from its very inception.

Photo: Alfred Russel Wallace, circa 1895, fi