HOW TO AGREE TO DISAGREE

The most significant political revolution of the modern era is the idea that dissent is not rebellion.

The prevailing view for thousands of years was that a society cannot tolerate dissidents in its midst. The result was unbearable suffering for anyone suspected of deviating from the norm. Perceived as traitors and therefore a grave danger to society-at-large, dissidents were universally targeted, discriminated against, tortured and killed.

Jewish history is full of such persecutions, and we are all familiar with the attempts by ancient Persians, Greeks, Romans, Christians and Muslims to eliminate Jews and Judaism simply because Jews refused to accept the authority of a dominant power or creed.

But we are not unique. The Romans were equally brutal with early Christians, who themselves turned out to be completely intolerant of any kind of dissent. Christian “heretics” were executed by Christians as a matter of course for centuries, the last one hanged by the Spanish Inquisition as late as 1826.

Meanwhile, Muslim dissenters continue to be murdered by their co-religionists to this day.

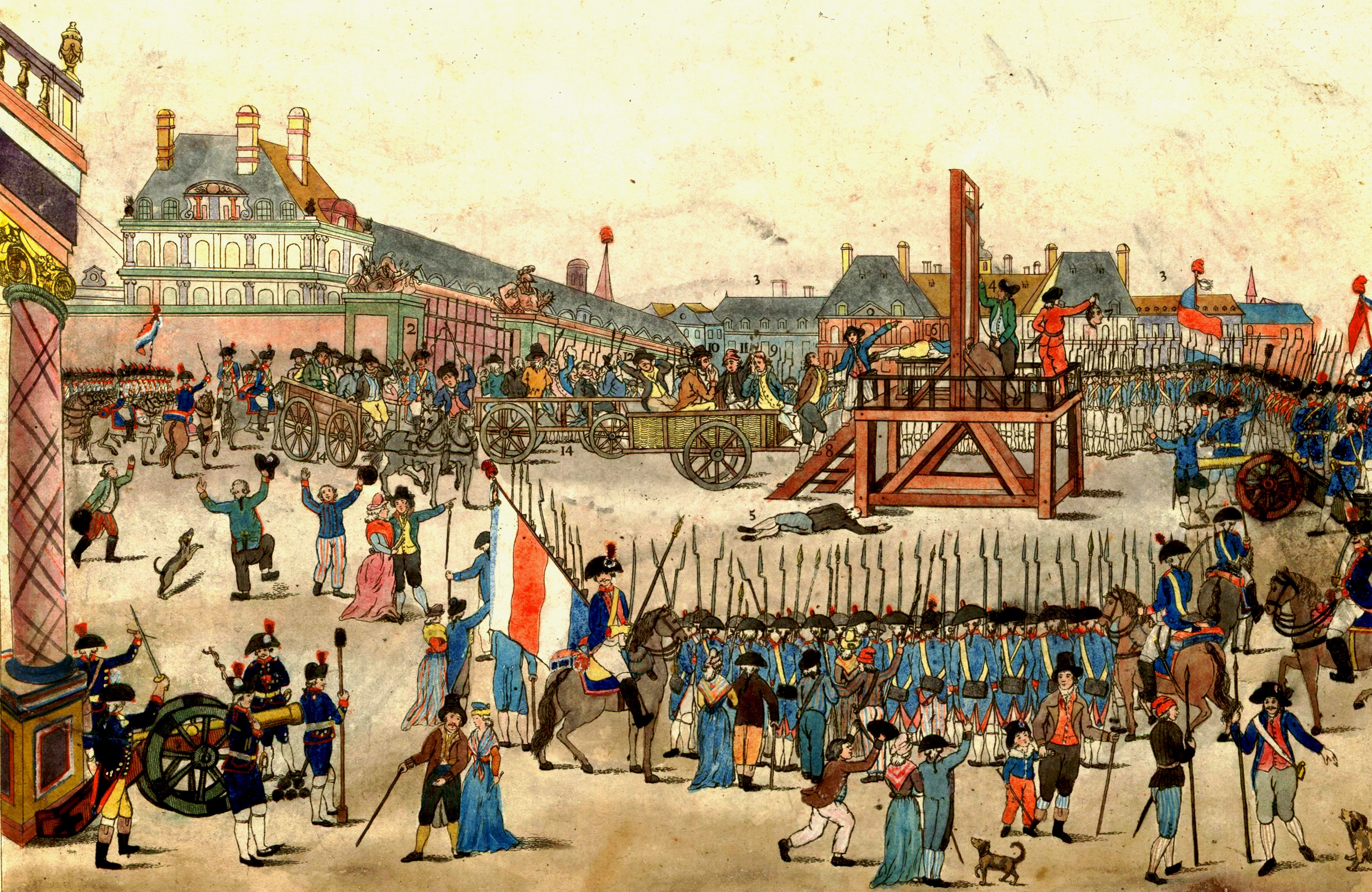

And people were not just killed for religious dissent. During the French Revolution’s yearlong “reign of terror”, more than 16,000 were guillotined – all of them for expressing viewpoints that clashed with the views of those in power.

Eventually France came to its senses, and with the execution of the killing frenzy’s primary advocate Maximilien Robespierre in 1794, the idea that vocal opposition amounted to an existential threat was abandoned in favor of freedom of belief and expression, ideals that have become the hallmark of a free society.

Three years earlier, the United States added the First Amendment to its constitution. This supplement to the country’s foundation document was added to prevent Congress from ever getting in the way of individual freedoms, such as the freedom to practice a religion, the freedom to speak freely and publicly on any subject without fear of official sanction, and the freedom of the press, among others.

The effect of this revolutionary idea has been profound. We can all immediately recognize an oppressive regime when we see one, using the First Amendment as our yardstick. We have also come to accept that people are entitled to live in and benefit from a society, even if they profoundly disagree with some fundamental aspect of that society’s ideals.

Or, as one of the founders of Methodism, George Whitefield (1714-1770), put it, “we can agree to disagree,” a phrase that entered popular culture after it was quoted as part of a generous-spirited eulogy delivered at his funeral by one of his most staunch opponents, John Wesley (1703-1791).

But are there limits to this axiom of modern values? The answer is tentatively, yes, and there have been rare instances in which it became clear that First Amendment freedoms cannot be treated as a blank check, most famously in the 1919 United States Supreme Court case, Schenck v. United States, when Judge Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. established that the First Amendment did not protect speech that encouraged people to resist military service in a time of war, or as he famously put it, “the most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic.”

In my view there is an additional limitation that should be applied to freedom of speech, one that does not revolve around constitutional rights, but is nonetheless equally important.

The modern State of Israel was founded on the same principles of democratic rights and individual freedoms as are found in the rest of the western world. You only need to glance at the Israeli press, or familiarize yourself with Israel’s national discourse, to see how this ideal has been embraced to its core.

And yet there is something palpably uncomfortable about the freedom of expression in Israel that undermines the viability of that freedom, and even of the state itself. I am referring to the unbridled aggression and bristling discord that threatens to tear the country apart.

The Torah portion of Kedoshim contains one of the most powerful expressions of human compassion ever composed (Lev. 19:18): וְאָהַבְתָּ לְרֵעֲךָ כָּמוֹךָ אֲנִי ה – “you shall love your neighbor as yourself, I am God.”

The great Talmudic sage, Hillel, informed a prospective convert not to do to others that which he did not want done to him, telling him that this principle was all he needed to know, as it contained the entire Torah. A century later, R. Akiba called the ideal of loving your neighbor as you do yourself the most important Torah principle of all.

But what does it really mean? If someone is your friend, why would you need an instruction to love them? And if they are not your friend, why should you love them? Besides, how is it possible to love someone as much as you love yourself? What exactly does loving yourself actually mean?

There are several Hebrew words for ‘friend’, but the one chosen for this directive is curious in that it contains the same letters as the Hebrew root word for ‘bad’. Perhaps the Torah is telling us that although we may not be perfect, and our views or way of life may seem wrong to others, we nonetheless expect to be treated with respect, compassion, and even love, by those who are different or think differently to us.

For this reason, to the extent that any of us feels the need to express our disagreement with others, God directs us to be mindful of how we articulate those opinions by instructing us to reflect on how we would want those who disagree with us to articulate their disagreement.

We are entitled to our opinions, and to disagree with others. We are also entitled to express our opinions, even if they are a minority view. But confrontation and hostility must always be completely out of bounds.

We may agree to disagree, but we must remain agreeable.

Photo: The execution of Robespierre and his supporters on 28 July 1794. (Source: Gallica Digital Library, available under digital ID btv1b6950750j, Public Domain, Link)