DOING YOUR BEST

When the first day of Rosh Hashana falls on a Shabbat, we don’t blow the shofar. Do you know why? You probably think the answer is that the Torah says you can’t blow shofar on Shabbat, so we don’t blow shofar when it’s Shabbat, even though it’s Rosh Hashana. It’s simple, right?

Actually, it’s not simple at all. As far as the Torah is concerned – and the Torah is God’s word – you can and should blow shofar on both days of Rosh Hashana, even if it falls out on Shabbat. That is God’s law. But the rabbis of the Talmud had other ideas. Indeed, the not-blowing-shofar-on-Shabbat law offers a fascinating insight into the workings of the Talmud, and into Talmudic law. The Mishna in Rosh Hashana (29b) states:

יוֹם טוֹב שֶׁל רֹאשׁ הַשָּׁנָה שֶׁחָל לִהְיוֹת בְּשַׁבָּת

בַּמִּקְדָּשׁ הָיוּ תּוֹקְעִין, אֲבָל לֹא בַּמְּדִינָה

מִשֶּׁחָרַב בֵּית הַמִּקְדָּשׁ, הִתְקִין רַבָּן יוֹחָנָן בֶּן זַכַּאי

שֶׁיְּהוּ תּוֹקְעִין בְּכׇל מָקוֹם שֶׁיֵּשׁ בּוֹ בֵּית דִּין

When the Festival day of Rosh HaShana occurs on Shabbat, in the Temple they would sound the shofar as usual. However, they would not sound it in the rest of the country outside the Temple. After the Temple was destroyed, Rabban Yoḥanan ben Zakkai instituted that the people should sound the shofar on Shabbat in every place where there is a court of twenty-three judges.

At first the Gemara suggests that the source for this is a scriptural verse (Lev. 23:24): שַׁבָּתוֹן זִכְרוֹן תְּרוּעָה – “a rest (day), memory of a blast” – which seems to indicate that on Shabbat you only have a memory of the shofar blast, but not the shofar blast itself.

But the Gemara immediately queries this suggested scriptural evidence. After all, argues the Gemara, if that were the case, why is shofar sounded on Shabbat in the Beit Hamikdash? If it is forbidden, it should be forbidden in the Temple as well? Also, if it is forbidden to blow shofar on Shabbat, because it is a musical instrument – you wouldn’t need a special verse to tell you it is prohibited.

Rava explains that blowing a shofar on a Rosh Hashana that falls on Shabbat is not prohibited by Torah law. But, says Rava, quoting his teacher Rabba, the rabbis were concerned that because only an expert can sound the shofar blasts, it might happen that a non-expert who wants to hear the shofar on Rosh Hashana might carry the shofar four cubits in a public domain to get it to an expert who would then blow it for him. But by doing so, no doubt in the pursuit of fulfilling the mitzva of shofar, they would desecrate the laws of Shabbat – and therefore the rabbis banned shofar blowing on Shabbat.

Meanwhile, in the Temple, which is an enclosed place – the shofar was sounded; and in a city with a major Beit Din of 23 dayanim, where there will certainly be a shofar-blowing expert on hand for everyone, the shofar was also sounded. According to most commentaries, once Yavneh was disbanded, about a century after the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple, the shofar stopped being blown on Shabbat – and so the law has remained to this day, and until the rebuilding of the Beit Hamikdash.

It is a remarkable fact that Chazal, the Sages of the Talmud, had the authority to suspend a Torah law.

This authority is rooted in the verse that instructs: עַל־פִּי הַתּוֹרָה אֲשֶׁר יוֹרוּךָ וְעַל־הַמִּשְׁפָּט אֲשֶׁר־יֹאמְרוּ לְךָ תַּעֲשֶׂה לֹא תָסוּר מִן־הַדָּבָר אֲשֶׁר־יַגִּידוּ לְךָ יָמִין וּשְׂמֹאל – “You shall follow the word they give you, from the place chosen by God, ensuring you act according to all their teachings.”

Various Hassidic commentaries note that it would be unimaginable for the Sages to deny the blessings of one of our most cherished mitzvot – blowing shofar on Rosh Hashana – merely because of concerns over a few people who might make the mistake of desecrating Shabbat laws.

Which must mean that the Sages recognized that somehow, whatever it is that we achieve by blowing and hearing shofar on Rosh Hashana is not required if falls on Shabbat. In other words, whatever the shofar typically achieves is naturally accomplished by Shabbat itself.

I love that idea and believe it must be true. But the rationalist in me is still conscious of the fact that the shofar obligation is suspended, but not abolished – which means that if these fears didn’t exist, the obligation would still prevail, and we would have to blow shofar on Shabbat.

As far as I’m concerned, this undeniable fact only adds to the incredible sensitivity of Chazal to the value of any mitzva that any of us might do, or more precisely: the negative impact of any violation of the Torah that one of us might find themselves committing inadvertently – the possibility of such a violation is so concerning to Chazal, however unlikely it is to happen, and however infrequently, that all of us no longer hear the shofar on Shabbat until the Beit Hamikdash is rebuilt.

Isn’t that incredible? Think about it – had Chazal not instituted this restriction, how often over the course of hundreds of centuries of Jewish history do you think this violation might have occurred? Half a dozen times? A dozen times? In tens of thousands of locations across the world! And yet, Chazal saw fit to institute this ban. That, my friends, is how important it is to them that no one ever drifts across the red line into “aveira” territory.

Sometimes we think we are doing our best, and we think we’ve covered all the bases. But is that really true? Are we matching up to the guiding light of Chazal? For them, every loophole needed to be closed, and every possibility of failure had to be addressed. Novices who study the Talmud are always taken aback at the rabbis’ obsession with even the minutest details of Jewish law. We live in a big-picture world where if something is more-or-less ok, then it’s ok. But each of us, in our own field, know that this isn’t true.

If you’re a doctor, you can’t be “more-or-less ok” at diagnosing or treating disease – the smallest mistake can cost someone their life, or their mobility, or their eyesight, or their general health. If you’re an accountant, you can’t be “more-or-less ok” at filing tax returns. If you leave just one line out, or get the numbers wrong – it’s a disaster, and potentially a criminal offense. If you’re a lawyer, you can’t be “more-or-less ok” at representing your client. Every detail of the law needs to be considered in putting together a good lease, or formulating the best legal strategy. You’ve got to do your best.

And our conduct as faithful servants of God is no different. We can’t be satisfied with being broad-brush Jews who are “more-or-less ok”.

We must be the best that we can be. No detail is too small, and no possibility of failure can be overlooked as immaterial. The lesson of not blowing the shofar on Shabbat is that even the smallest chance that we might not do something properly has to be a foremost consideration. In fact, it’s not good enough to do your “more-or-less ok” best – you have to dig deeper, and find the real “best” in you, so that you are truly at the top of your game.

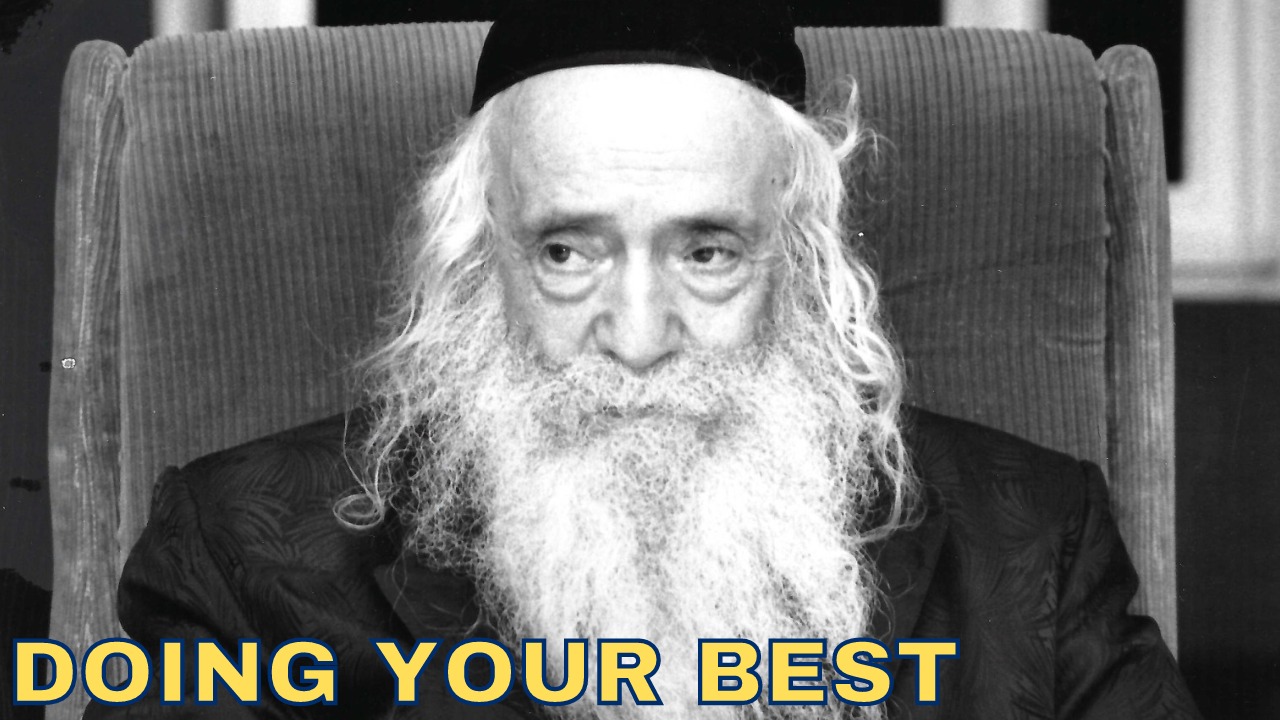

On that note, I would like to end with a story about the Klausenburger Rebbe – Rabbi Yekusiel Yehudah Halberstam. In times of deep darkness and amidst the most harrowing trials of life, there are some souls that shine brighter than the stars, emerging as legends of unwavering spirit and resilience. Such a soul was the Klausenburger Rebbe.

Born in 1905 into the distinguished Sanz Hasidic dynasty, the Klausenburger Rebbe rose to spiritual leadership at a very young age. As the rabbi of the strictly-Orthodox prewar community in Klausenburg (Cluj), he provided guidance and wisdom. He was also an outstanding scholar, whose knowledge of rabbinic literature and Jewish law was simply outstanding.

Tragically, in 1944, with the Nazi takeover of Hungary, his world turned into a stormy sea of chaos. His life was forever shattered when the Nazis ruthlessly slaughtered his wife, and ten of his eleven children – the eleventh died soon after the war in a refugee camp – and most of his followers. And yet, although the Rebbe was imprisoned within the cold, barbed-wire fences of these evil concentration camps, his spirit, like an unextinguishable flame, burned even brighter.

He would often recall one particularly chilling story from those grim days. The Rebbe was with a group of Jews who found themselves trapped under the scorching summer sun. They were thirsty to the point of losing consciousness, and no one was giving them water to drink – they expected to die. But the Rebbe’s heart was filled with unwavering faith, and he urged his comrades to dig into the earth. God intervened, and water miraculously sprouted forth from the ground, quenching their thirst and reigniting their lost hope. “In our darkest hour,” the Rebbe told his companions, “God still shows His love for us.”

Time after time the Klausenburger Rebbe escaped death. A Nazi bullet once pierced his arm, and he expected to die from the untreated wound. But he was determined not to give up and used a leaf to staunch the bleeding. That day he made a solemn vow: if God allowed him to survive, he would channel his entire being into saving others who were in dire straits, and one day he would build a hospital to save his fellow Jews from death. He was true to his word, and after the war he built Laniado Hospital in Netanya, which continues to save lives every day – to this day.

Emerging from the war’s shadow, the Klausenburger Rebbe’s battle scars did not deter him. With a mission burning inside him, he set out to rebuild, brick by brick, building by building, person by person, the Jewish communities that had been ravaged.

His quest eventually led him to America, where he was introduced to a range of Jewish philanthropists by his acolytes – so that he could ask for their assistance in his quest to rebuild the Jewish world after it had almost been destroyed.

One of the philanthropists the Klausenburger Rebbe met was Mr. Sam Feuerstein. Samuel C. Feuerstein (1893-1983) was a New England textile manufacturer, best remembered as a generous supporter of Jewish educational causes. In 1943, Mr. Feuerstein was one of the founders of Torah Umesorah, and he was chairman of the board of the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America (the “OU”).

The Klausenburger Rebbe did not hold back at their meeting. He shared his grand vision with Mr. Feuerstein: how he was going to build communities, schools, hospitals — a range of institutions that would breathe life back into the lives of all the broken Jews who had survived the Holocaust. The Rabbi’s physical frailty was evident. He was in his 40s, but he looked as if he was in his 60s. And yet, his eyes blazed with the hope of youth, and they reflected galaxies of dreams. His enthusiasm that day, as always, was infectious.

Mr. Feuerstein was visibly impressed and moved, and he wanted to help – really, he did – but at the same time, he knew that the calls on his charitable foundation were abundant. So, he shook the Klausenburger Rebbe’s hand and told him, “Rebbe, I’ll try my best.”

The Klausenburger Rebbe kept his grip on Mr. Feuerstein’s hand, leaning forward with burning intensity. “When I was the rabbi of Klausenburg,” he told Mr. Feuerstein, “I was treated like royalty. I was like a king. Every step I took, people rushed to assist me. I never had to carry a bag, there was always someone to carry it for me. I never had to walk more than a block, there was always someone ready to drive me. I always thought that I was “trying my best” – and in a sense, I was doing it, kind of: I did whatever I had to do, and I got everything done.”

“But when I arrived in concentration camp, I learnt what “trying my best” really meant. It meant carrying 50-pound sacks on my back for miles, wearing only torn clothes and torn shoes. It meant staying alive with no food and no sleep. Mr. Feuerstein: my muscles ached, my feet bled, and my soul was in tatters. And yet, every day I found new reserves, so that I could do my best. That, Mr. Feuerstein, is what “trying my best” actually means. It means going to your limit, and then going beyond that limit.”

Mr. Feuerstein was silent. The Rebbe’s words had touched him deeply. And from that day on he became one of the Rebbe’s most generous supporters.

The message of the Shofar not being blown on Shabbat is that whatever you think is your best may not be your actual best. Maybe there is a detail you overlooked. Chazal wanted to remind us that your “more-or-less ok” best is never quite good enough.

Let it never be adversity that teaches us this life lesson. Rather, let it be the powerful legacy of Jewish tradition, which demands that we excel and do our real best in every given situation – so that we meet our maximum potential for ourselves, for our families, for our community, and for God.