BEWARE OF THE GOLDEN CALF

There have been countless unnecessary deaths and critical infections in the Orthodox Jewish community during the coronavirus pandemic. There, I said it. You’re all thinking it, but I’ve said it. And now that it’s out there, I would like to explore this topic, not because I wish to pursue some kind of vendetta, but rather because I want to do whatever I can to prevent any more unnecessary deaths. So please read this article carefully, and act accordingly. Your life, and the future of our ancient faith, could depend on it.

One of the anomalies of Jewish survival has always been the fact that we have danced between the raindrops, and that we are culturally preprogrammed to be non-conformist. When everyone else in the world blindly marched in one direction, we stubbornly marched in the other, snubbing our nose at accepted wisdom and established convention. And truthfully, in the final analysis, this characteristic has served us well – after all, here we are after thousands of years, survivors against all the odds.

But ironically, what has historically been among our greatest strengths has over the past few weeks proven to be our most dangerous weakness. And most jarringly of all, it has been the more committed and most devout Jews among us who have unfortunately suffered the worst, with the percentage of coronavirus victims in the Haredi community exceeding averages by numbers that are so shocking, that the entire Jewish world, both within and beyond that community, is reeling with dismay and pain.

And although the Haredi world has now by-and-large fallen into line with stay-at-home orders or enforced quarantine, the cost in lives and health among Haredi Jews to date has been unbearable, and even now there remains those on the fringes who insist that all attempts to shut down public life in order to stem the tide of COVID-19 and the death toll that follows in its wake are the work of evil satanic forces.

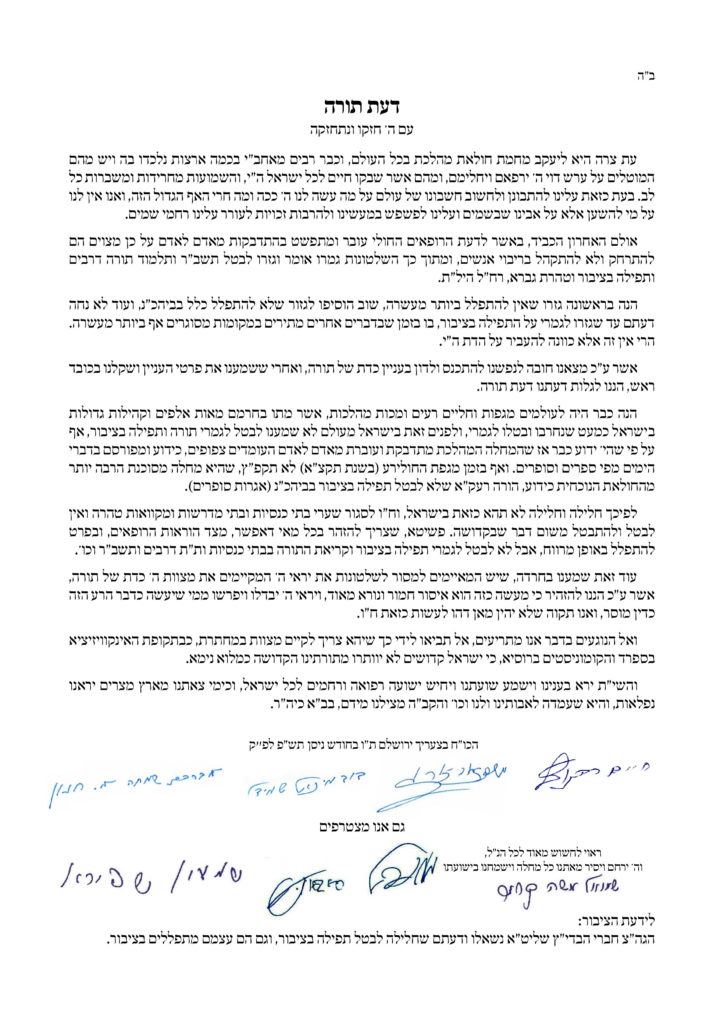

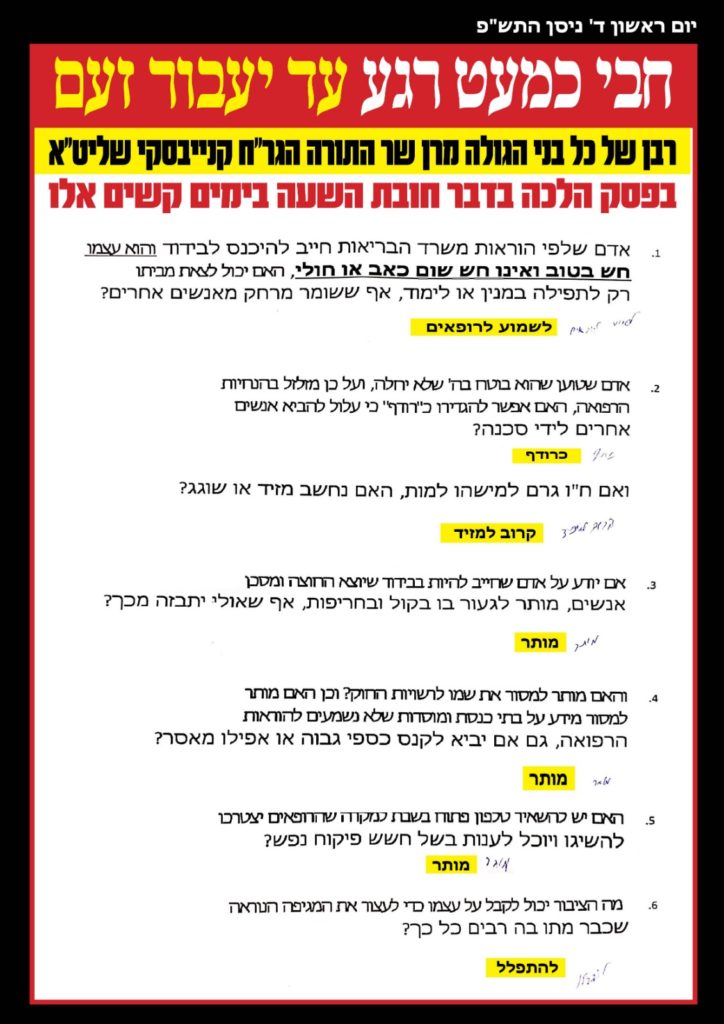

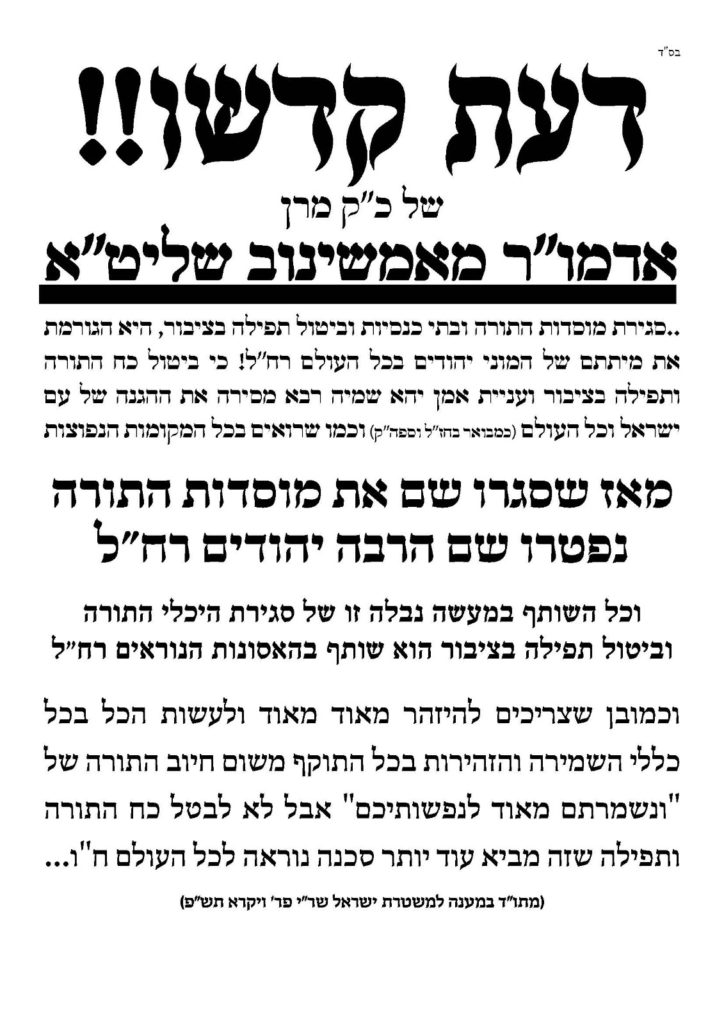

In fact – and bear with me here – I would like to interrupt the flow of this article to call these people out. Last week, for example, the Satmar dayyan in Jerusalem, Rabbi Moshe Zev Zorger, spoke out publicly against shutting down synagogues and schools, telling his audience that “closing synagogues and preventing thousands of Jews from answering amein yehei shmeih rabbah and praying as a congregation is itself a great and fearsome danger, more grave than any other danger, especially at a time of plague.”

Zorger went on to suggest that the secular administration in Israel was deliberately targeting religious Jews – an absolutely ludicrous claim – and warned against “people leveraging the verse ‘you must safeguard your souls’ (Deut. 4:15) in order to destroy souls.”

Frankly, extremist drivel from a so-called rabbi like Zorger (who may very well be a Torah scholar, which only makes matters worse) would never normally merit my attention, nor indeed any reaction from those who consider his utterings to be the rantings of a fanatic. Usually, one would just shrug and move on. But in this situation ‘careless talk costs lives’ – and yes, this vicious campaign by Zorger and his vile fellow-travelers has actually cost lives. Real people have listened to them and then died, or passed on the infection to others who have died.

Another extremist fanatic in Israel, Rabbi David Michael Shmidel, told supporters last week that keeping Orthodox Jewish schools open was worth any risk: “Think about it – if the danger is that the virus is carried in the air, why not just tell people to stop breathing altogether? Do you know why? Because then people will die. And that is exactly the point – we will all die if we stop children studying Torah together.”

This mind-boggling ‘logic’ has since been published in Shmidel’s name, demonstrating just how far removed from reality both him and Zorger actually are. (Incidentally, Zorger and Shmidel have been engaged in a smoldering feud for years – proof, if you need it, that they are both addicted to hatred, and hatred is never confined to ideological enemies.)

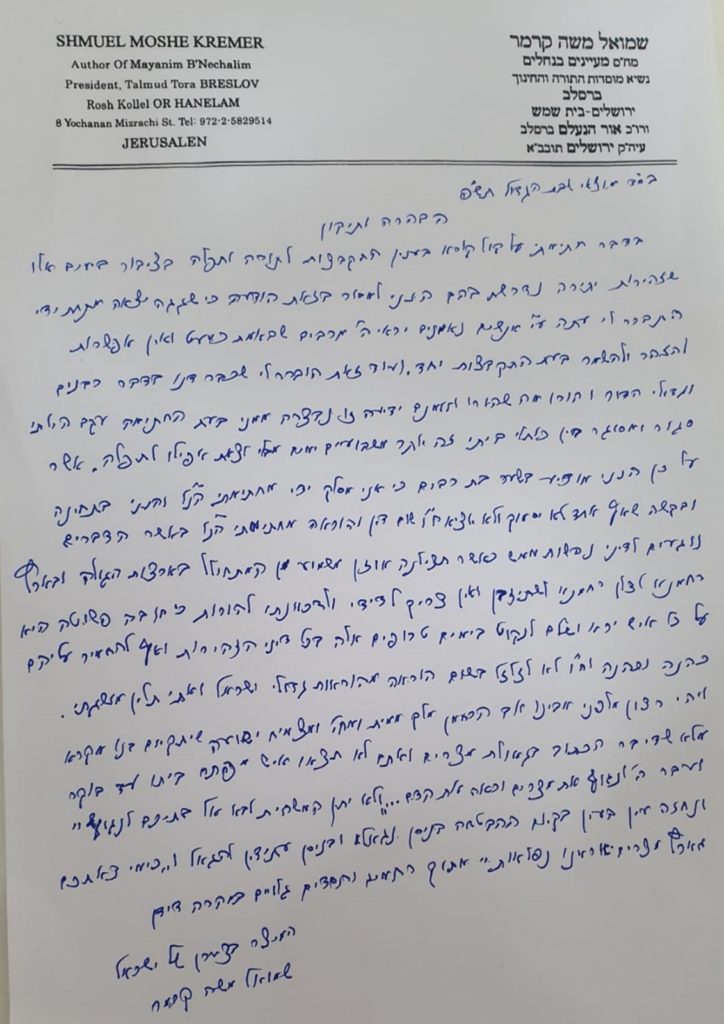

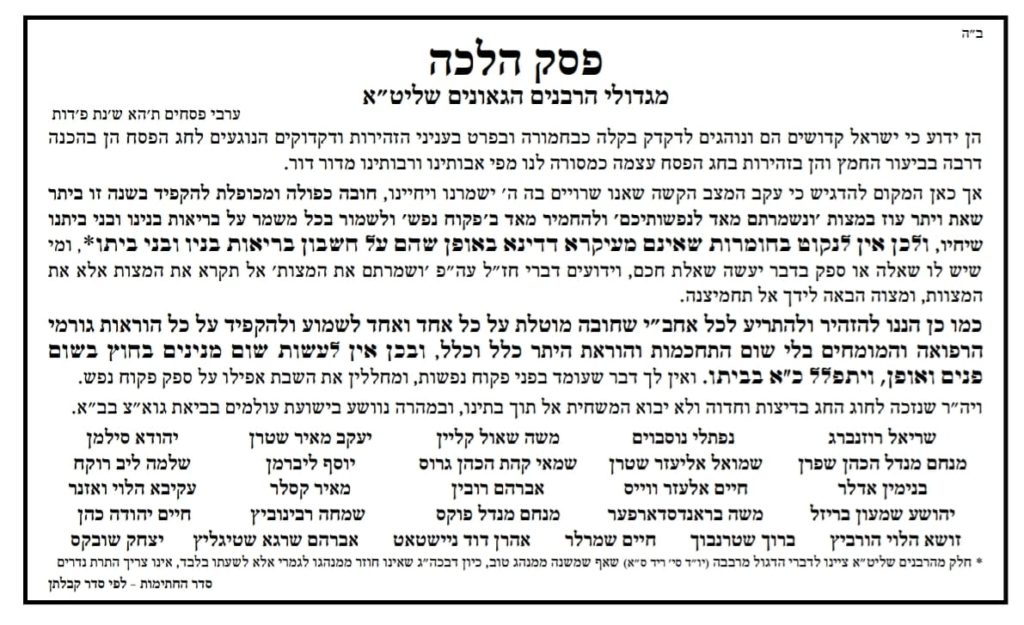

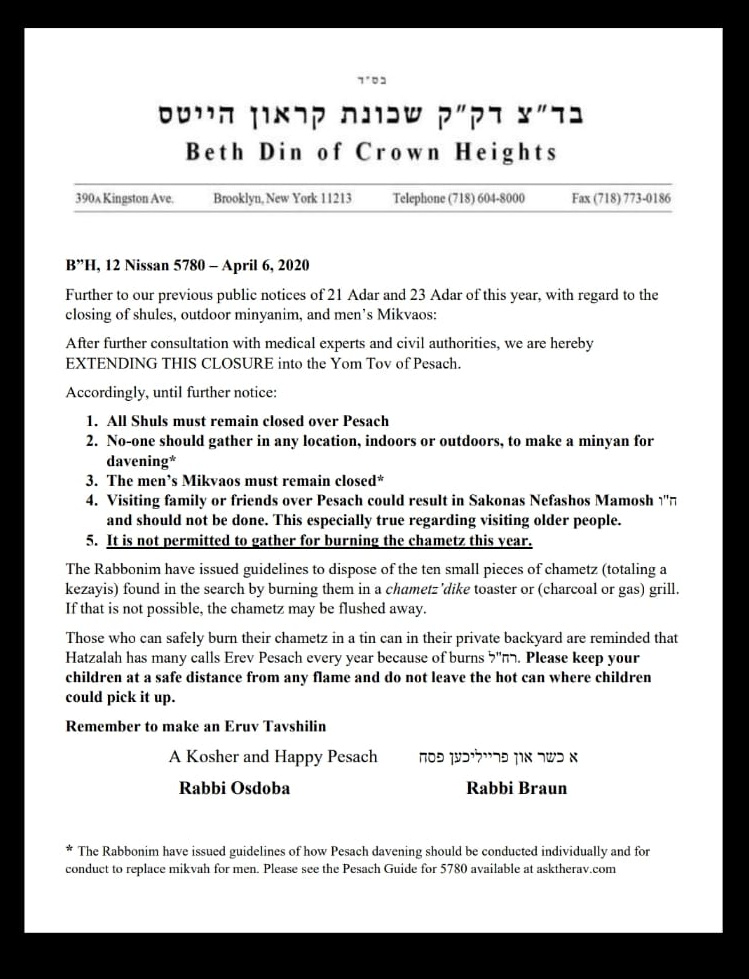

Of course there are significant Haredi rabbis who have publicly urged their communities to stay indoors and not to pray with a minyan — in Israel there is Rabbi Yitzchak Ehrenfeld, Rabbi Eliyahu Schlesinger, Rabbi Tzvi Weber, Rabbi Yisrael Bunim Schreiber, among others; in the UK, Dayan Chanoch Ehrentreu and Rabbi Shraga Feivel Zimmerman, among others; and in the United States Rabbi Elya Brudny and Rabbi Mordechai Dovid Ungar of Bobov-45, among others; all of whom are currently isolated and themselves praying without a minyan. Recently, Rabbi Chaim Kanievsky of Bnei Brak sent out a strong note to forbid public gatherings, after having earlier allowed them – a development that will hopefully significantly change the playing field.

In any event, despite all the evidence proving that coronavirus is both deadly and extremely contagious, and despite significant rabbinic opposition to these gatherings (albeit after too much procrastination, and not across the board), backyard and porch minyanim continue to meet, even as infections rise at a rapid pace and bodies pile up in makeshift morgues in New York.

And foolishly, funerals of some of the rabbis who have died from coronavirus are announced and then attended by hundreds of mourners, none of whom are wearing masks or are socially distanced from each other, resulting in a draconian police response on the spot, and who knows what else in the weeks that lie ahead.

Catastrophically, and not unrelatedly, the Haredi community is exponentially overrepresented in hospitals and ICUs – in Israel, and in cities with Haredi communities across Europe and the United States. Evidently, in a closed world where everything you do or don’t do is governed by assent or disapproval from your leadership, a wink is as good as a nod, which is as good as a full-blown endorsement.

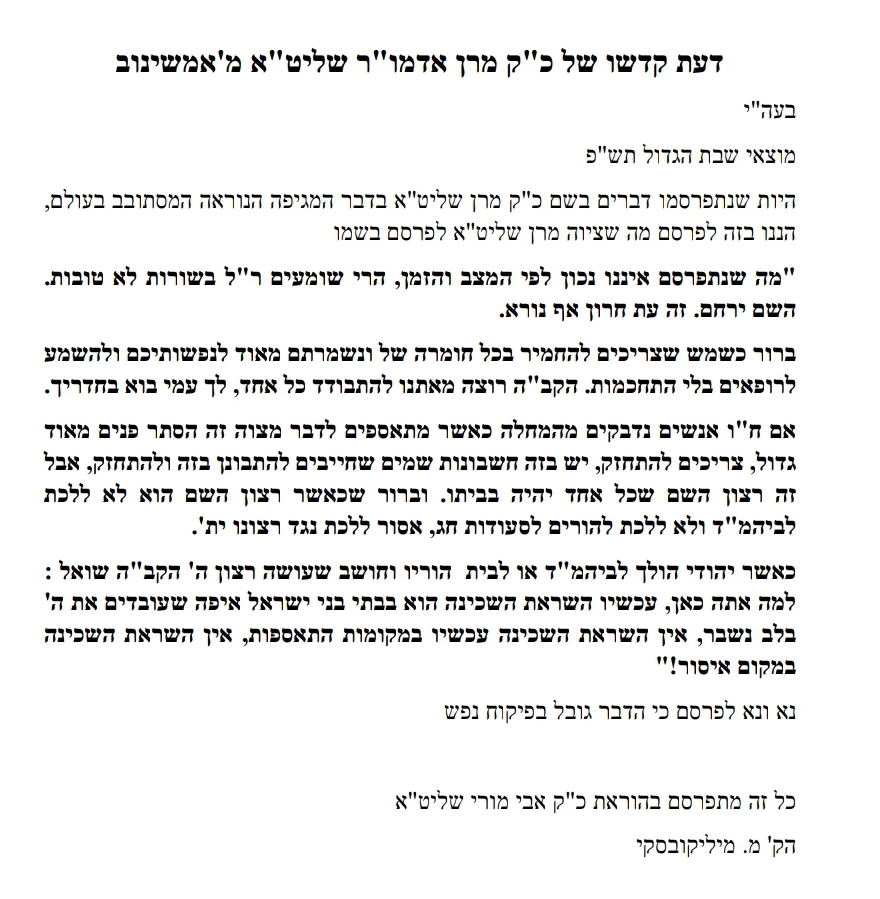

Finally – thankfully!! – in the past day or two, activists in the Haredi community have prevailed on their leaders in Israel and the United States, who have issued sternly worded letters to their communities and followers to discourage gatherings – even for family members who wish to join each other for the Seder.

Of course it is never too late to save lives, but consider the fact that these pronouncements come some three weeks after government and local authorities shut down social interactivity, which itself took place at least a week after many individuals and groups had opted to do it themselves, without any kind of mandatory obligation, just based on emerging evidence.

I believe that in the fullness of time there will be – and should be – a difficult reckoning regarding the failure of meaningful rabbinic and lay leadership in the midst of this crisis as it unfolded. But as we all struggle with an ongoing reality that is agonizingly difficult to bear – with our community and family lives upended beyond recognition, especially with the upcoming festival of Pesach which will involve multiple adjacent days of confinement without phone or electronic communication, or indeed any ordinary social interaction, I would like to offer a hallowed Jewish perspective based on traditional sources – one which demonstrates that not only is what we are doing to save ourselves from death and ill-health correct, but that those who protest to the contrary are misrepresenting Judaism, warping it beyond recognition into something that is utterly unacceptable to God.

Let me begin by quoting the Hasidic master Rabbi Chaim of Czernowitz – author of Be’er Mayim Chaim and a follower of Rabbi Yechiel Michel, the Maggid of Zlotchov – in a piece that addresses the opening verses of the third chapter in Kohelet (Ecclesiastes). This series of verses is an arresting passage describing the dialectic choices open to man at different times in his life, including ‘a time to embrace’ and ‘a time not to embrace’.

What exactly does Kohelet mean by ‘a time not to embrace’? And how are we to reconcile this negative moment with our duty towards God that surely requires us to be in full embrace with Him on an ongoing basis?

The Be’er Mayim Chaim explains it beautifully:

“And so, God, who desires our physical and material preservation – as the verse states (Lev. 18:5) “[you shall] live by them [i.e. the mitzvot]!” – also created an aspect of limitation [in our relationship with Him]. Sometimes [He] encompasses the aspect of “a time to embrace” [while at other times He reflects the aspect of] “a time to distance from embrace” (Eccl. 3:5). All of it is there for the good and benefit of humanity, so that they can survive while still actively doing His worship. When there is great intellectual and spiritual resoluteness (‘gadlut hamochin’), it is fine to express one’s love and reverence for God abundantly, with full force. But at a time of uncertainty (‘katnut hamochin’), the only thing that matters is to sustain one’s bodies. And this [should] all [be done] with the love and reverence [for God that is relevant] to this aspect. Behold, this aspect [of our relationship with God] is like a screen dividing a person from the pure Light, which is too bright to look at all the time, to enable sensible decisions, by which the person will go on to live and survive.”

There are times that – for reasons we do not necessarily fathom – closeness to God using the embrace methods with which we are all so familiar, is actually not what God wants from us. And, most importantly, this situation is for our own good. Perhaps it is similar to the idea I once heard from Shlomo Carlebach about breaking the matza into two pieces at the beginning of the Seder, only to eat that broken piece at the end of the Seder to signify that the Seder meal is complete.

“Unless something is broken,” he told me, “you will never truly value it when it is complete. Only through experiencing brokenness are we able to gain an understanding and an appreciation of what we have when we have it all.”

The broken matza at the beginning of the perfect Seder is the ideal symbol for Pesach, the moment when we emerged from the brokenness of slavery into the perfection of being God’s Chosen People. Without the first, the second would not have been possible.

But the broken matza is also a universal symbol of our relationship with God. Our ‘time to embrace’ is juxtaposed by ‘our time to not embrace’ so that the embrace has value that could have never been achieved without the lack of embrace. And most strikingly of all, as the Be’er Mayim Chaim indicates, if you insist on embracing God at the wrong time you will ultimately cause yourself immeasurable harm.

Which means that those who insist on retaining every aspect of their Jewish lives even in the face of incontrovertible proof that now is not ‘a time to embrace’ are defying God, and are certainly not demonstrating their faith.

And actually, what they are doing is even much worse than that. The Talmud in Menachot (99a-b) quotes Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish: אמר ריש לקיש פעמים שביטולה של תורה זהו יסודה, דכתיב ‘אשר שברת’ – אמר לו הקב”ה למשה יישר כחך ששברת – “Reish Lakish says, Sometimes the dereliction of Torah is its foundation, as it is written: “[the Tablets] which you broke” (Ex. 34:1). God said to Moses: ‘Yishar Kochacha!’ (your strength is true)”

The verse quoted by Reish Lakish is drawn from Ki Tissa, in the narrative of the Golden Calf. While Moses was at the top of Mount Sinai communing with God, the Jewish nation decided to create a Golden Calf to replace him. Without telling Moses exactly what had happened, or how he should react, God told him to hurry down the mountain and address the developing crisis.

Moses descended as quickly as he could with the two tablets in his hands; but as soon as he discovered what the nation had done, and without referring back to God for instructions, he shattered the tablets – the precious record of the Ten Commandments personally given to the nation by God only a few weeks earlier. And then, only once he had done that, he began the process of resolving the situation.

To the untrained eye, this extraordinary act of destruction seems to be the epitome of sacrilege. And yet, not only does Reish Lakish cite God’s approval, but he stunningly presents this act as the very foundation of Torah.

Seemingly, the second pair of tablets emerged out of the destruction of the first, which is why the very verse that records God’s instruction to make new tablets is used by Reish Lakish as proof of His assent for what Moses had done to the first set, to underscore this exact idea – that the Torah’s continuity, as represented by the second pair of tablets, was contingent on him having broken the first pair. Indeed, Rabbeinu Gershom comments that the word ‘foundation’ used by Reish Lakish really means ‘perpetuation’.

Moses realized that whatever the nation had heard at Mount Sinai, clearly the desperate need for there to be a Moses at their helm, or his proxy in the form of a Golden Calf, undermined the very notion of monotheism. That version of the Torah was not God’s Torah at all, and it needed to be cast aside while the nation recalibrated and understood the error of creating it in the first place.

To be sure, there were always going to be those who could not and would not abandon the concept of a Golden Calf, those who thought they could not last for even a moment without this aspect of their faith – the absence of which could only end with their utter obliteration. But by shattering the tablets and grinding up the Golden Calf, Moses irrefutably proved that this was not the case at all.

Fascinatingly, Moses remained the leader and point of inspiration for the Jewish people over the next forty years, and indeed for all time, which seems to show that it was not that they had been mistaken about him being important, only that they had been wrong to turn him into a Golden Calf. Once this mistake was corrected, exemplified by the shattering of the first tablets and the creation a second pair, the foundation of Torah was saved, like a corrupted file on a hard drive that with some slight modifications is back where it should be – and with that act, the Torah could be perpetuated.

This profound teaching of Reish Lakish has echoed throughout Jewish history. From time to time, for one reason or another, Jews have drifted away, however slightly, from the foundational principles of Torah, and created Golden Calves for themselves, all of them rationalized as intrinsic to Jewish continuity. But time and again we have seen that such man-made impositions have backfired for their champions, resulting in circumstances that have threatened their existence or indeed precipitated their oblivion.

Right now we are at exactly such a moment. Moses is crying out to us “Whoever is for God, [come] to me!” (Ex. 32:26) – beseeching us to abandon our Golden Calf so that we can live on to perpetuate the Torah, just as we have done until now, but from here on without those Golden Calf aspects that have trapped us into self-destruction.

Too many have already died in the vain attempt to keep the first tablets intact. What God wants from us is to embrace the second pair of tablets, so that when we emerge from this horrific nightmare we will have clarity of faith and will be able to embrace Him with true gadlut hamochin, expressing our love and devotion in the close proximity that we so crave, but which for the moment is just beyond our reach.

I know that time is close, and in the meantime I am urging you not to flout stay-at-home or quarantine rules, even if this means sacrificing some valued aspects of your religious lives, such as praying with a minyan or being with your family for Seder or yomtov meals. The evidence all points to the fact that it is what God wants. May it be His will that this is all over very soon, so that we can all be back together again, celebrating every aspect of our Judaism, among family, friends and community.