BEAUTY IS IN THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER

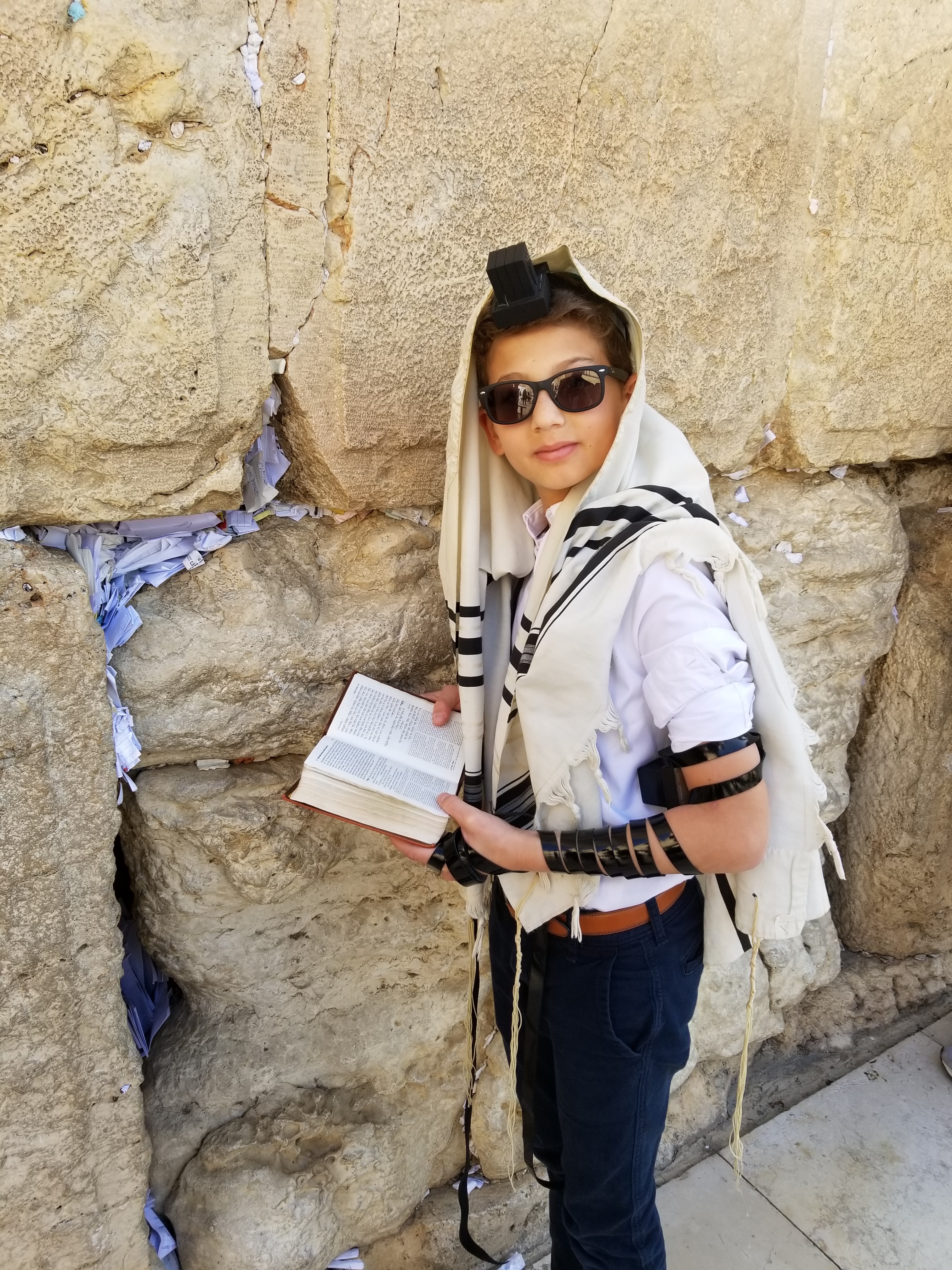

A few weeks ago, at the Western Wall in Jerusalem, our youngest son Uri put his Tefillin on for the first time.

In May he will turn thirteen, the age of adulthood for Jewish boys. In anticipation of that milestone moment – when he will become obligated to observe all those mitzvot that until now have merely been educational experiences – Uri prepared himself for the mitzva of Tefillin, which he will don every day for the rest of his life.

What more appropriate place to initiate him into this primary religious obligation than at the most sacred site of Jewish tradition – the location of our Temple in Jerusalem.

But why are Tefillin considered so important? The odd-looking black boxes with attached leather straps are undoubtedly the most enigmatic religious accessories in Judaism—not only because they are purely ritual, but also because they occupy such an elevated place in our tradition and heritage.

The mitzva of Tefillin is the first mitzva mentioned in the Shema prayer that we recite each morning and evening, when we declare our faith in God, and promise to love Him in every possible way. That the first method of demonstrating this love is expressed through wearing Tefillin conveys just how central this mitzva is to our faith.

And not a month goes past without an inspiring Tefillin story. Just last week, the Jewish Journal reported the miraculous reunion of a 91-year-old Polish Holocaust survivor, Al Kleiner, with his Holocaust-victim brother’s Tefillin, brought by his cousin from Poland to Israel after the Holocaust, where they remained forgotten until last year.

Out of the blue, Al’s cousin’s daughter discovered the little red velvet bag with embroidered initials and immediately realized whose they were. She sent them to Al’s family in Los Angeles, and, amidst great emotion, he put them on for the first time since having been in hiding from the Nazis in 1943-4.

Some years ago, I was in Northbrooke, Illinois, for High Holydays, and the synagogue president told us how he had recently sent his late Holocaust-survivor father’s Tefillin to New York to have the parchments checked.

These were Tefillin that had remained hidden with his father throughout his time in concentration camp, which he had diligently put on each day, from his thirteenth birthday until his passing.

The sofer called a few days later, his voice trembling.

These are the most perfect Tefillin parchments I have ever looked over during my entire career as a sofer – and for them to be decades old, and to have gone through the hell of Auschwitz – your father’s father, who purchased these Tefillin, must have been an extraordinary man, because I can assure you these Tefillin did not come cheap.

The late Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, famously launched a “Tefillin campaign” in the weeks leading up to the Six-Day War, to ensure that as many post-barmitzva Jewish boys and men as possible put on Tefillin each day.

This remarkable campaign has since resulted in millions of Jews putting on Tefillin in thousands of locations all over the world, often after being stopped in the street, or in some other public place, by intrepid young Lubavitch yeshiva students.

During the early stages of the computer revolution, Rabbi Schneerson was once asked where computers could be found in the Torah. He replied simply, “Tefillin” – and went on to explain that the essence of computers was efficient thinking and enhanced connectivity, and Tefillin are the same, enabling us to think more spiritually, and connecting our heart, our hands and our brain at the start of each day so that they unite with each other with the sole purpose of serving God.

In the Torah portion of Ki Tissa, Moses is granted a glimpse of God’s “back” after being told he would not be able to see God’s “face” (Ex. 33:23).

Rashi, quoting the Talmud, explains that Moses was shown the knot of God’s Tefillin, that for us is located at the nape of the neck when Tefillin are worn. This mystical allusion is understood to mean that only part of the link between man and God was revealed to Moses, while everything else remained concealed.

According to another Midrash, a more complete vision was granted to the second century sage, Rabbi Akiva, and his contemporaries. Using a source text in Job (28:10), the Midrash underscores Rabbi Akiva’s supremacy: וְכָל יְקָר רָאֲתָה עֵינוֹ – “all of your glory my eyes have seen”, and tells us that “this [verse] refers to Rabbi Akiva and his friends—things which were not revealed to Moses were revealed to them.”

Commenting on the use of the word “yekar” (glory) in Megillat Esther, the Talmud in Megillah (16b) informs us that this word refers to Tefillin.

How are we to understand that Moses only saw the back of God’s Tefillin, while Rabbi Akiva was able to see God’s Tefillin in all its glory? Embedded in Judaism is the idea that Moses was the greatest prophet who has ever lived, and Rabbi Akiva, notwithstanding the fact that he was a great rabbinic leader, was not even a prophet.

The innovative nineteenth-century Hasidic master, Rabbi Mordechai Yosef Leiner of Izbitza, suggests an astonishing distinction between Moses and Rabbi Akiva. Moses transmitted the foundational text of the Torah, and therefore had to convey the bad along with the good, specifically punishments for transgressing the word of God, acknowledging the possibility of human failing, and a rift between man and God.

Meanwhile, the Mishna in Makkot (7a) records a statement of Rabbi Akiva and his friend Rabbi Tarfon, who said: “had we been members of the Sanhedrin, no person would have ever been executed.”

As far as they were concerned, no Jew could ever be so distant from God that they would potentially be liable for capital punishment.

And, according to Rabbi Akiva, “Love your neighbor as yourself” (Lev. 19:18) is the most important principle of the Torah (JT Nedarim 30b).

If we understand that Tefillin represents the potential perfection in every Jew and our duty to love every Jew notwithstanding any disconnection with Judaism, Rabbi Akiva’s view of God’s Tefillin was complete, unmarred by any doubt or cynicism, while Moses’ view was somewhat less favorable.

During the month of Adar, and specifically the festival of Purim, we are expected to see everyone as if they are resplendent in Tefillin, Judaism’s representation of God’s essence in all of us. It is our faith’s version of seeing the glass half-full, as opposed to seeing it as half empty.

Photo: Uri Dunner puts on Tefillin for the first time at the Kotel in Jerusalem