BE HONEST WITH YOURSELF

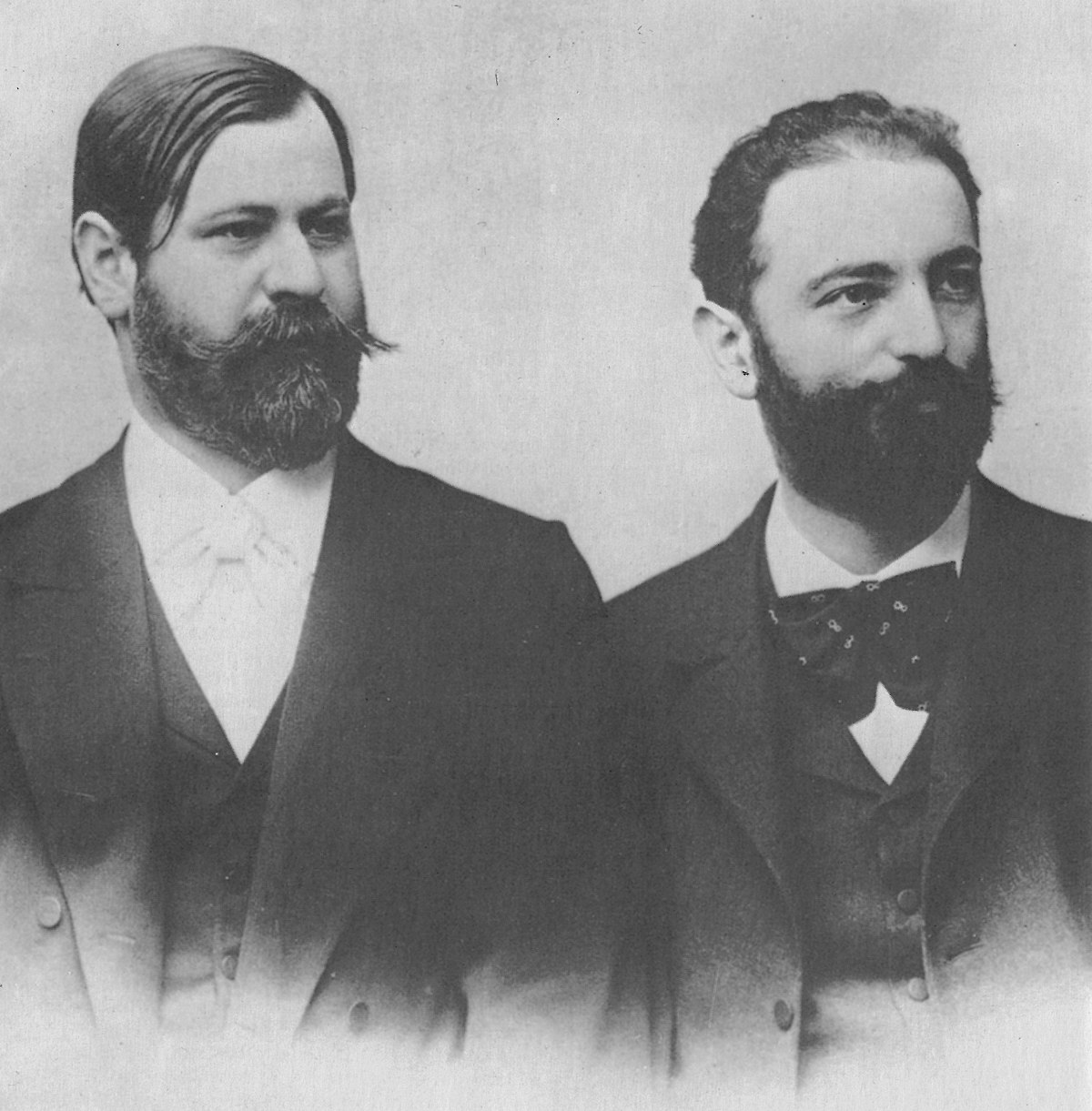

In October 1897, Sigmund Freud wrote to his close friend and confidant, the idiosyncratic German-Jewish otolaryngologist Wilhelm Fliess, inter-alia telling him that “being entirely honest with oneself is a good exercise.”

This piece of advice, among many others Freud gave Fliess before falling out with him in 1904, might have been lost to posterity had those Freud trusted followed his strict instructions to destroy all their correspondence.

Luckily, Freud’s copies of these important letters were saved by his acolyte Princess Marie Bonaparte, who was herself a psychologist, as well as being a great-grandniece of Emperor Napoleon I of France.

The importance of the Freud-Fliess correspondence cannot be overstated; the letters chart the development of psychoanalysis in its earliest stages, ideas later expanded upon and formalized by Freud.

But the most important detail of Freud’s vision of psychoanalysis and its goals is the quote I mentioned earlier about self-honesty being the ultimate aspiration and guarantor of positive mental health.

Peeling away every level of detail about one’s life only has true value if it leads to a point when one can be “entirely honest with oneself.” In other words – not just honest, but “entirely honest.”

One of the greatest and most influential figures of modern Jewish history was a rabbinic educator called Nota Hirsch Finkel, better known as the “Alter of Slabodka” Rabbi Nosson Tzvi Finkel.

Rav Finkel lived more-or-less contemporaneously with Sigmund Freud, although I doubt he was familiar with the founder of psychoanalysis. And yet, Rav Finkel’s educational philosophy seems to have intuitively followed similar lines to Freud; he aimed to get to the essence of each of his students, so that they could maximize their strengths and work on their weaknesses.

Basing himself on the Mussar (Jewish ethics) ideals he had picked up and honed during his youthful studies at Kelm yeshiva, in the late 1800s Rav Finkel founded and quietly led a yeshiva in Slabodka, a nondescript suburb of Kovno, today Kaunas in Lithuania. His fame grew, and many of Slabodka’s students went on to become significant religious leaders and educators in the Jewish world.

In 1924, Rav Finkel dramatically announced he was moving his yeshiva from Lithuania to Palestine, and later that year most of the faculty and student body moved to Hebron, where they remained until the horrific Arab massacre of Jews in Hebron in 1929, after which they relocated to Jerusalem, where his yeshiva remains to this day, thriving and successful.

Slabodka and Hebron yeshiva graduates include some of the greatest orthodox rabbis of the twentieth century, such as Rabbis Aharon Kotler, Yitzchak Hutner, Yaakov Kamenetzky, and Eleazar Menachem Man Shach, along with countless other influencers and leaders – Ezriel Carlebach, founding editor of both Yediot Ahronot and Maariv newspapers; Professor Saul Lieberman of Jewish Theological Seminary; and Chaim Herzog, sixth President of Israel.

As far as Rav Finkel was concerned, “Gadlut Ha-Adam – ‘a person’s greatness’ – can only ever be achieved through self-awareness, which more-often-than-not requires painful self-honesty.

Partial self-awareness is insufficient, as unless you have got to the bottom of who you are, you will never be the greatest version of yourself that you can be. And this ideal is beautifully illustrated by Rav Finkel’s insight on Parshat Toldot.

It is immediately evident that Esau is the villain, although the narrative does not offer any hard facts as to why that should be the case. Yes, he was red and hairy at birth, and yes, he was an outdoors guy and a hunter. But why is that bad?

Perhaps it is because being a “man of the field” is a rejection of spiritual pursuits. But, to be fair, there are plenty of farmers and hunters who are good people, faithful to God and responsible providers.

What makes Esau so bad? Not everyone is cut out to be a spiritual trailblazer. Meanwhile, without much explanation, Jacob leverages Esau to part with his birthright for a mere bowl of lentil soup.

Unusually, Rav Finkel devotes a lot of attention to Esau’s personality, analyzing his strengths and weaknesses so that we can better understand why the Torah regards him as such a villain.

In discussing Esau, Rav Finkel poses a profound but important question: how did Jacob know Esau was willing to sell his birthright?

Esau had returned home to find everyone mourning for Abraham, while Jacob was cooking lentil soup, a traditional mourning food. But Esau was hungry, and all he wanted to do was eat, prompting him to demand “give me that red stuff now.”

Rav Finkel notes that whenever anyone prioritizes something material without pausing to reflect, no amount of intervention will help, and it is this weakness that is Esau’s hallmark.

Self-awareness is all about cultivating one’s consciousness to pause before acting. But Esau was totally impulse-driven, a trait that undermined the responsibilities of his birthright. Remarkably, Esau was self-aware enough to realize that he lacked the discipline to be the person his role required of him, and this was how Jacob knew he could negotiate the sale.

But here comes the kicker, a unique insight that only someone of Rav Finkel’s profound understanding of human nature can ever reveal.

Esau believed his birthright unworthiness was the result of him not being an elevated person – in itself, one might think, a great feat of self-honesty – but at the same time he was not aware that he was a bad person, nor did he recognize any real need for self-improvement.

Had Esau been truly honest with himself, he would have admitted that his “self-honesty” was not actually so honest, and in actual fact he had sold his birthright for instant gratification. But, as it turns out, even when Esau was being honest, he was not being completely honest.

The greatest test of self-awareness is not admitting your weaknesses, because even then you could be using contrived “self-awareness” as a cover to delay facing up to who you actually are.

Or, as Freud wrote to Fliess in 1897, it is not being self-honest that is crucial, it is being “entirely” self-honest.

Image: 1890s photograph of Sigmund Freud (left) and his friend Wilhelm Fliess (right).