AND FINALLY, THE MIRACLE OF CHANUKAH

You will be forgiven for never having heard of Chaim Selig Slonimsky.

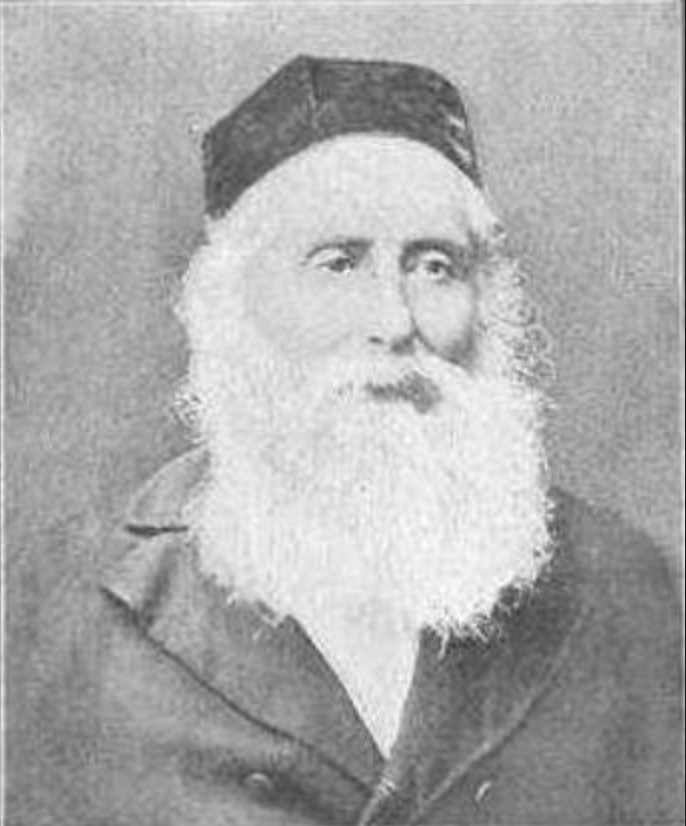

A minor celebrity in nineteenth-century Eastern Europe, he was an avuncular man with solid credentials as an astronomer and scientist, notorious for his traditional Jewish appearance, and particularly for his expansive white beard.

In an age when secular studies were universally frowned upon in strictly-orthodox circles, Slonimsky was considered safe – a committed observant Jew who excelled in the world of science, but whose convictions were firmly in the right place.

Legend has it that Slonimsky stumbled on the formula for duplex telegraphy in 1859, but rather than patenting it, he filed his discovery away, telling his wife “now let us see how long it will take them to figure it out!”

And although American scientist Moses Gerrish Farmer had successfully demonstrated a rudimentary form of duplex telegraphy in 1856, it was not until 1871 that Joseph Barker Stearns figured out a serviceable version that was almost identical to Slonimsky’s proposal, and his system was then further improved upon, and more importantly, commercialized, by Thomas Edison in 1874, paving the way for the modern telephone.

Remarkably, Slonimsky’s innovation would never have come to light had Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin not tried to use it as part of an anti-American propaganda campaign in 1952, when a pair of distinguished Russian scientists published a paper which essentially said “Russia got there first!”

Slonimsky’s stellar reputation in the traditional Jewish world took a severe knocking in late 1891, when he published a short article in his newspaper, Hatsefira, which questioned the veracity of the celebrated miracle of Chanukah, namely the discovery of a cruse of uncontaminated oil for the Temple menorah which should only have lasted 24-hours, but which lasted a full eight days, the time period required to produce new oil.

Citing Maimonides’ omission of the particular words in the Talmud that convey this miracle (see: Hil. Chanukah 3:2), Slonimsky suggested that Maimonides was clearly of the opinion that the “miracle” of Chanukah was not in fact supernatural. Rather, the victorious Hasmoneans lit the Temple Menorah each night in front of the crowds celebrating their God-assisted triumphant victory, but once people had left, the priests extinguished the flames so that enough oil remained to light up the menorah each subsequent night until new oil was produced.

Slonimsky’s article set off a firestorm of protest among traditional rabbis, and countless articles and pamphlets were published to refute his thesis. Critics claimed Slonimsky was an irredeemable heretic and challenged him to recant.

But he was unintimidated and responded defiantly, refusing to retract even the smallest detail of his radical proposal. Ultimately the excitement died down, and Slonimsky went on to live to a ripe old age, dying in Warsaw at the age of 94.

Slonimsky’s detractors were certainly right about one thing – that his dismissal of this story would lead to a general ambivalence towards both the festival of Chanukah, and towards the authenticity of Talmudic legends. As recently as this past October, an article appeared in the Huffington Post under the headline ‘The Truth(s) About Hanukkah’, in which the (Jewish) writer trivializes every aspect of the festival, and particularly the miracle story.

Nevertheless, it is an unavoidable fact that the account of the miraculous oil was first recorded hundreds of years after the Hasmoneans stormed Temple Mount and reclaimed the sacred site for the Jews. If it happened immediately following the victory, why was it not included in the two contemporaneous accounts of the rebellion against the Greeks, Maccabees I and Maccabees II?

While both these books speak of the Temple having had to go through a ritual cleansing process, neither of them mentions anything about a single cruse of oil lasting eight times as long as it should have. Surely this emblematic miracle was worthy of at least a single reference?

As if this is not puzzling enough, one must also wonder why we choose to focus on what is such a minor miracle, notwithstanding its supernatural aspects, when the headline story is surely the astonishing victory of a ragtag bunch of rebels against a professional army of trained combatants? Why did the Talmud feel the need for another hook to hang this festival on, when the success of the Hasmoneans was itself so extraordinary?

Numerous scholars have grappled with these questions and come to different conclusions to the one Slonimsky suggested.

Rabbi Dr. David Berger, for example, notes that Maccabees I has no record of any miracles whatsoever, while Maccabees II is brimming with miracles far more impressive than the long-lasting oil. On that basis, the omission of the oil miracle in a book totally devoid of miracles is hardly surprising, while the absence of a minor miracle in a book containing numerous superlative miracles is similarly predictable.

Other scholars point out that the Bimei Matityahu prayer, which summarizes the Chanukah story and was composed far earlier than the account in the Talmud, focuses exclusively on the military victory and omits any mention of the oil having lasted longer.

My own thoughts on this matter are rather more prosaic. When the victory was still fresh in people’s minds, and bearing in mind that the victors were all highly devout, the miracle of the oil, while undoubtedly noteworthy, took second place to the incredible – and miraculous – success of the Hasmoneans against the Hellenists’ bid to destroy Judaism.

But after the fall of Jerusalem to the Romans, and the later brutal crushing of the Bar Kochba revolt, the sages of the Talmud sought to refocus the Chanukah festival onto what had previously been seen as a minor detail – namely, a miraculous demonstration of God’s personal imprimatur on what occurred.

The miracle of Chanukah was ingeniously revived by the sages of the Talmud to bolster a festival that might easily have evolved into a God-free event, no different to the frequent anniversary celebrations of ancient military victories prevalent at the time. But by celebrating the miracle of the oil we are assured that this festival remains religious, and we are compelled to acknowledge Divine involvement in what was essentially a military victory against the Greeks.

This important point appears to have eluded Slonimsky, but to me it stands out loud and clear.

Photo: Chaim Selig Slonimsky, 1810-1904 (Public Domain)