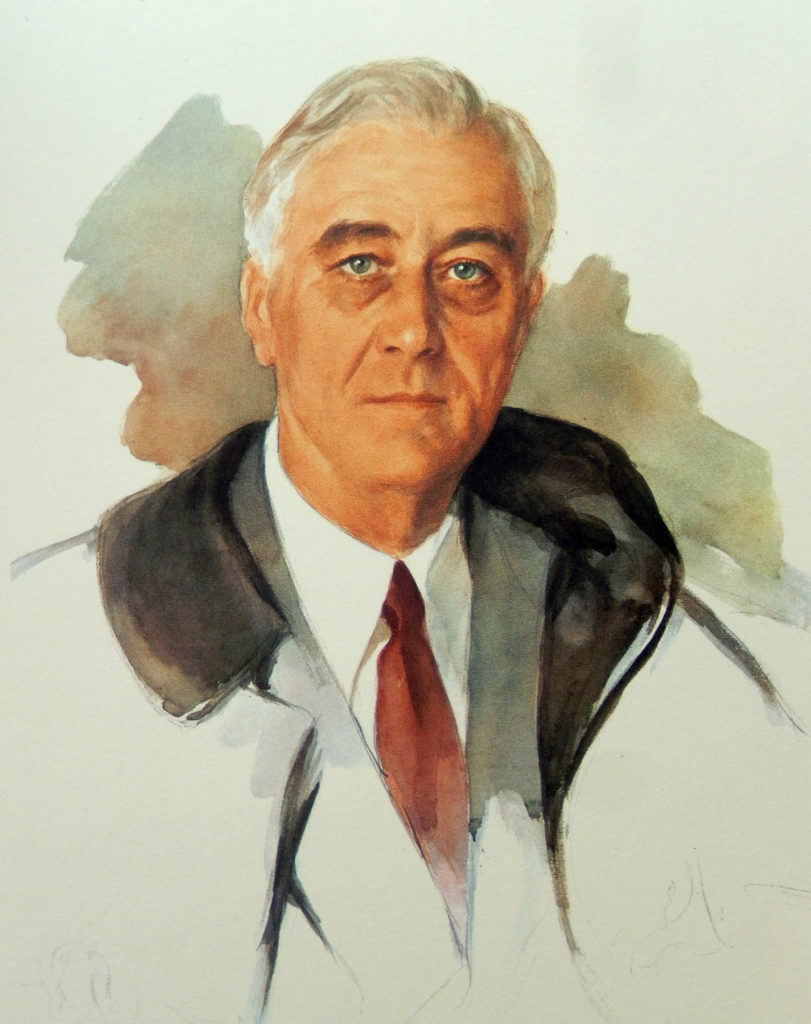

AN UNFINISHED WORK OF ART

On April 12, 1945, the Russian-born American artist, Elizabeth Shoumatoff, began work on a portrait painting at a sleepy private vacation retreat in Warm Springs, Georgia, known as the “Little White House”.

It was noon, and her subject was Franklin Delano Roosevelt, recently elected for his fourth term as president of the United States.

An hour later, over lunch, the president complained of a severe headache, and slumped over, unconscious. The attending physician confirmed the president had suffered a cerebral hemorrhage, and by

Understandably, Shoumatoff’s portrait was never completed. It remained a partial depiction, becoming known as the Unfinished Portrait, and today it hangs on the wall at the Little White House, now a President Roosevelt memorial museum. Curiously, it joins numerous other unfinished works of art, music and literature considered by scholars to be an intriguing but important marginal element of the creative world.

Perhaps the most famous example of this phenomenon is Franz Schubert’s “Unfinished Symphony”, while the most jarring is undoubtedly the bizarre portrait by Benjamin West of the delegates at the Treaty of Paris in 1783, which, as a result of the British delegates refusing to pose with their American counterparts, is a painting with half the canvas totally bare.

Interest in this unfinished phenomenon has gained quite a bit of traction over the past few years, and was the subject of a major art exhibition at the Met Breuer in New York, in 2016.

The exhibition included over 190 artworks, many of them left incomplete by their makers for reasons unrelated to the art itself, but in that state offering insights into the creative process along with other aspects of the artist.

Also featured as part of the exhibition were works considered

But Renaissance-era

One such piece presented at the exhibition – Lick

After completing the busts using a rough mold, Antoni “unfinished” them by licking the ones that were made of chocolate and using the soap ones when she washed, “stopping once she had arrived at her distinctive physiognomy.”

As with much of this kind of modern art, I am not quite sure what to make of it, but I am definitely very taken with this idea of

Kelly Baum, one of the curators of the Met exhibition, suggested that

“an unfinished picture is almost like an X-ray, [allowing] you to see beyond the surface of the painting to what lies behind … [it] demands your creative and imaginative investment in a picture, because you have literally to fill in the blanks.”

It is exactly this that makes the unfinished art so compelling, and it is also this that offers a wonderful insight into the temporary nature of the Mishkan, and particularly to explain a strange contradiction in the Torah regarding the final sum collected by Moses in his fundraising campaign for the Mishkan building project, described as both “enough” and “too much” (Ex. 36:7).

Rabbi Chaim ibn Attar,

The Midrash teaches that the Mishkan needs to be seen as a microcosm of the world, and the process of constructing the Mishkan is compared to the creation of the world.

The Mishna in Avot (5:6) declares that “

The idea that God ran out of time as Shabbat approached is patently ridiculous, as noted by Maharal, who proposes that the statement in Avot is only there to teach us that the world is incomplete – not because God was unable to complete it, but because God wanted it that way.

Just like the modern version of

We must constantly be aware that our world – as beautiful as it may be as a piece of art, and even if we feel utterly filled with faith in God – is missing some element, however tiny, that we just cannot quite get to no matter how hard we try.

The Mishkan reflects this reality – it is beautiful and has everything it needs, but it is still temporary and incomplete. Even though the nation brought everything that the Mishkan needed, and completed the construction of every element, there was still more

Our lives are also like the Mishkan:

Unfinished painting: Treaty of Paris by Benjamin West, 1783 (Public Domain)