AN INTERESTING CAST OF CHARACTERS

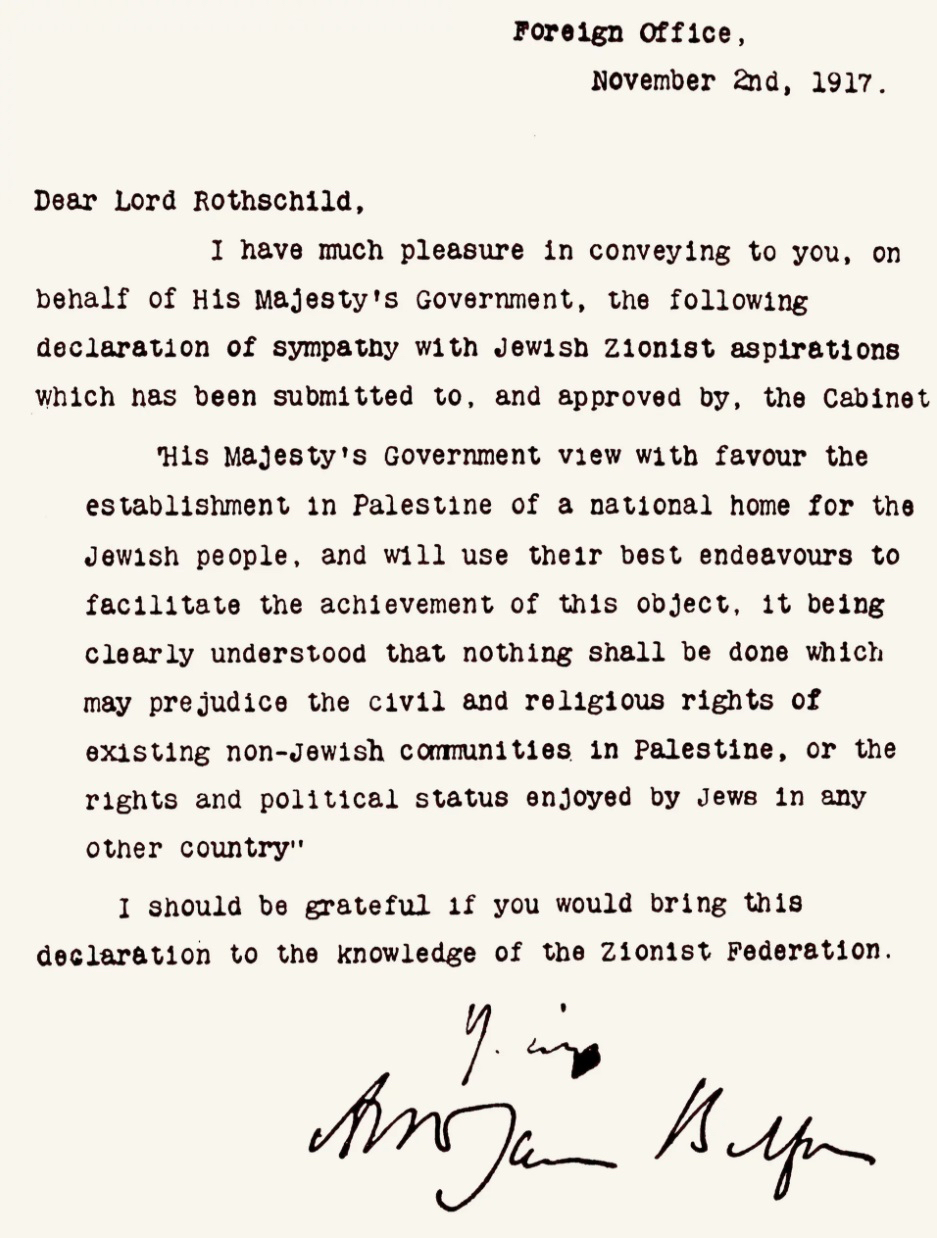

A century ago this week, Lord Arthur Balfour, British foreign secretary and former prime minister, dispatched his now famous 67-word letter to Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild, addressed to the latter’s residence in central London.

Rothschild was hardly known for his political activism. Although he had been a member of parliament for eleven years, his primary interest was zoology, and in 1908, at the age of 40, he resigned his post at NM Rothschild & Sons, his family’s legendary bank, and for the rest of his life devoted himself full-time to collecting and cultivating species of animals and birds from around the world.

Notwithstanding his fascination with zoology, Walter was the scion of the world’s preeminent Jewish dynasty, and even while burying himself in his personal obsession he was unable to escape his Jewish leadership obligations.

Nonetheless, that this should have been expressed as enthusiasm for Zionism was by no means a foregone conclusion. The vast majority of Great Britain’s Jewish aristocracy – known as the “Cousinhood” due to multiple marriages between the various families – were deeply opposed to Zionism, and considered any expression of Jewish nationalism as a form of disloyalty to their British identity.

Two things influenced Walter’s enthusiasm for Zionism, the first personal, the second political, both seemingly random.

Towards the end of 1914, Chaim Weizmann, not yet the prominent Zionist leader he would soon become, met with Dorothy “Dolly” de Rothschild, recently married to James, the son of Baron Edmond de Rothschild of Paris.

The nineteen-year-old Dorothy was smitten by Weizmann’s charismatic charm, and promised to introduce him to her cousin Walter. Dorothy was true to her word, and the introduction was made, after which Weizmann and Walter established a warm friendship that would ultimately prove crucial to the Zionist cause.

The second, more political event to influence Walter’s enthusiasm for Zionism, and the catalyst that turned him into a proactive lobbyist for Balfour to issue his declaration, was a statement published in The Times of London on May 24, 1917, authored by the virulent anti-Zionist Jew, Lucien Wolf.

The statement represented the strident views of the Conjoint Committee of the Board of Deputies of British Jews and the Anglo-Jewish Association, bodies dominated by the “Cousinhood” and other assimilated Jews, who deeply feared the consequences of being labeled a nation rather than a faith.

Wolf summarily dismissed “the Zionist theory which regards all the Jewish communities of the world as constituting one homeless nationality, incapable of complete social and political identification with the nations among whom they dwell”, and went on to renounce the suggestion that Jews should have any elevated political rights in Palestine in relation to the non-Jewish communities that lived there.

This brazen attack on Jewish nationhood was the culmination of a long period of festering enmity between assimilated British Jews and the Zionists. Walter Rothschild found the statement particularly disturbing, partly, perhaps, because it broadly represented the views of those from among his own social circle, but mainly because Zionism’s opponents had taken an internal Jewish fight outside the community.

Upon reading it, he immediately fired off a letter to The Times; it was published the following day.

“Our opponents, though a mere fraction of the Jewish opinion of the world, seek to interfere in the wishes and aspirations of the larger mass of the Jewish people… I can only again emphasize that we Zionists have no wish for privileges at the expense of other nations’ laities, but only desire to work out our destinies side by side with other nationalities in an autonomous state.”

That we have the State of Israel today is down to a teenage girl’s fascination with an Eastern European Jewish political charmer, and a British Jewish grandee only nominally associated with Jewish life feeling the need to react to a public attack against his adopted cause by friends and associates.

Of course we know that it was not random at all, and in retrospect we can see God’s hand behind these events at every turn, resulting in the resounding endorsement of Zionist aspirations on November 2, 1917 by Lord Balfour, representing the British Empire, at that time one of the world’s dominant superpowers.

Stunningly, it was exactly this aspect of the Balfour Declaration that was picked up by a leading rabbi of the time, Rabbi Meir Simcha HaCohen of Dvinsk, who had never previously expressed enthusiasm for or opposition to Zionism, or indeed any political cause affecting Jewish life.

Orthodox Jewish leadership, with very few exceptions, had traditionally frowned upon any attempt to return to Eretz Yisrael, or to deliver political advantage for Jews residing in Palestine. They based themselves on a Talmudic passage in Ketubot (110b-111a), which records “three oaths” imposed by God on the world – two of them incumbent upon Jews, the third on gentiles. Essentially, the oaths banned Jews from returning en masse to the Land of Israel, and from rebelling against the nations of the world, while gentiles were warned against behaving too oppressively against Jews.

Until 1917, the dominant view was that this Talmudic source limited Jewish attempts to alleviate the excesses of exile, and also proscribed mass immigration to the Holy Land. The Talmud is the primary source of Jewish law, and notwithstanding the many prophetic statements in Hebrew scripture that painted quite a different picture, it was this rather depressing outlook that became the accepted norm.

Rabbi Meir Simcha saw things differently. The Balfour Declaration had shifted contemporary reality beyond the “three oaths”. Without a Talmudic source to guide him, he turned to Hebrew scripture, where he found a congruent situation – the declaration of King Cyrus of Persia, as recorded in Ezra and Chronicles. Cyrus was a gentile ruler of a superpower who issued an edict permitting Jews to return from exile, ultimately resulting in the repopulation by Jews of the Land of Israel, and the rebuilding of the Temple.

There is no record as to what prompted Cyrus to issue his proclamation, but no doubt there was a cast of characters behind the Cyrus Declaration that included someone wily and charming, like Chaim Weizmann, a starry-eyed heroine like Dorothy de Rothschild, an unlikely hero like Walter Rothschild, and a Jewish assimilationist sellout like Lucien Wolf.

Ultimately, they, like their modern day counterparts, were only footnotes in God’s greater plan.

Photo: The original Balfour Declaration, currently at the British Library in London (Public Domain)