ALL THE PLEASURES OF THE WORLD

The story of Purim, as recorded in Megillat Esther, is a very unusual religious scripture.

Many aspects of the narrative make no sense when considered from a faith perspective. They seem to be distractions from what is surely the main theme of the story – the Jewish nation’s miraculous escape from a devastating state-sponsored genocide in ancient Persia.

Had the author of Megillat Esther wanted to deliver the salient points of this saga, he should probably have begun with a brief description of the Persian Empire, its mighty king, Ahasuerus, and followed that with a description of Esther’s elevation to royalty, as well as Mordechai’s role and his relationship with Esther.

He should then have described Haman, his plot, and the series of events that led to his downfall. And finally, he should have depicted Haman’s downfall that was followed by the appointment of Mordechai to a prominent position at the Royal Court.

After all, these are the details that encapsulate the essence of the story.

So why does Megillat Esther begin with such a detailed description of Ahasuerus’s parties and revelry? Who cares? Ancient kings and princes partied all day, every day. What possible significance do these details have in terms of the core narrative?

Moreover, why is the celebration of the first Purim festival described at the end of Megillat Esther in such detail? And why do we celebrate this festival so differently to the way we celebrate other Jewish festivals?

There is a strong stress on parties and revelry, on food gifts, and on giving charity. This kind of celebration is not evident anywhere else in the Hebrew scriptures as the formal way to celebrate a Jewish festival. What makes Purim so different?

The answer cuts to the very heart of the Purim story. Human beings are born into a world that is fully material, and all our senses are attuned to the very physical, very material world around us. We are instinctively hardwired to get the best out of that material world, and to do everything to ensure that we are fed, clothed, housed, and stimulated.

It is this reality that unlocks the meaning of the seemingly superfluous details at the beginning of Megillat Esther. The narrative deliberately records exactly how Ahasuerus reacted to his superlative success and supreme power — by endless debaucherous partying.

And it was not just any party; it was a party to end all parties. He was the mighty king, and he was intent on enjoying every moment.

Then, suddenly, Ahasuerus’s wife rebelled and became a party-pooper. No problem! Let’s get rid of that wife and find another wife.

Then, out of the blue, someone offers Ahasuerus mounds of cash to kill a bunch of people. No problem! Let’s kill some people and get really rich.

Megillat Esther’s King Ahasuerus absolutely personifies an absolute materialism that totally excludes God from the equation.

Meanwhile, the Jewish faith represents the polar opposite of this wanton hedonism. Although we, too, are human beings, beholden to our senses, and to the physical and material world, we are nonetheless charged with being ‘holy’ (Lev. 19:2). God expects us to be different. He expects us to relate to the Divine, despite being material beings, and as material beings.

And so, at the end of Megillat Esther, the Jewish nation are put in exactly the same situation as Ahasuerus had been in at the beginning of the story. They suddenly find themselves the powerful victors and are thrust into indescribable wealth and success.

What does their reaction look like? Do they turn into Ahasuerus? Or are they what God wants them to be?

Megillat Esther conveys the appropriate reaction — using material success as a way of getting closer to the Divine, rather than as a wedge that divides us from God.

Herein lies the most difficult challenge of material success. We can turn into Ahasuerus and Haman, or we can become Mordechai and Esther, and the Jews of ancient Persia.

We could revel and party, or we can turn our success into an opportunity to share, to become God’s partners in his material world by thanking God through using that material world.

We can give food gifts to our friends, and we can give charity to the poor.

We can have a festive feast with our family and friends with the primary focus of thanking God.

None of this has anything to do with showing how great and mighty and powerful we are; rather it is a demonstration that we recognize how our success is God’s success.

And that is why the detailed descriptions of Ahasuerus’s parties at the beginning of Megillat Esther are such an essential part of the narrative. Without these details we would not understand the end of the story, which records how the Jewish community of ancient Persia reacted to their victory and success.

Ahasuerus’s parties and fondness for self-serving materialism are offset by the Jewish reaction: turning material success into a vehicle for spirituality and Godliness.

What a powerful message, and how apt that this message is one that has been carried by Jews wherever they have lived since that time.

So how can we best be true to this ideal?

The answer is simple. Purim is about using materialism to connect us to each other.

People can party for the sake of selfish pleasure, or they can eat together and become closer to each other.

People can give gifts to patronize and feel good about themselves, or they can give gifts because they want other people to have what they have.

People can give charity and tell themselves how terrific they are, or they can give charity to ensure that those not as lucky as them can also benefit from their success.

That is the message of Purim. Megillat Esther is all about showing us the two alternatives, and telling us howwe should behave as Jews, as opposed to those who don’t get the message.

This week is the anniversary of my late brother Benzi’s tragic passing in 2008. Benzi died just a couple of days after Purim, when he had distributed over two million pounds to hundreds of individuals who had come to him for financial help.

Of course, in reporting his tragic death, the newspapers described how rich he was, citing the sums of money he had recently given away, as well as the size and location of his house, and the make of his car.

But as his brother I know that none of these things really mattered to him if he would not have been able to share them with others.

Benzi epitomized the message of Purim, always seeing his wealth as a means of getting closer to God, rather than as a vehicle for material pleasure. May his memory be a blessing.

Mir Yeshiva Tribute to Benzi Dunner z”l

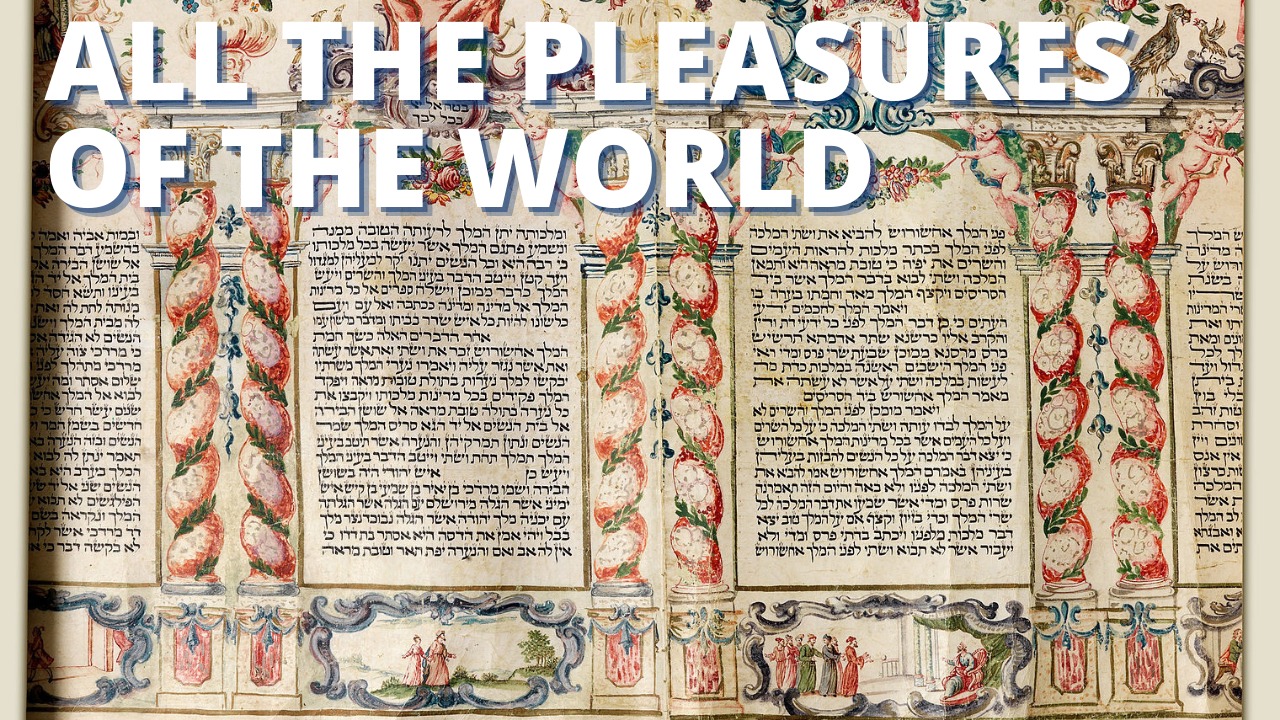

Image: Antique Megillat Esther parchment scroll (Public Domain)