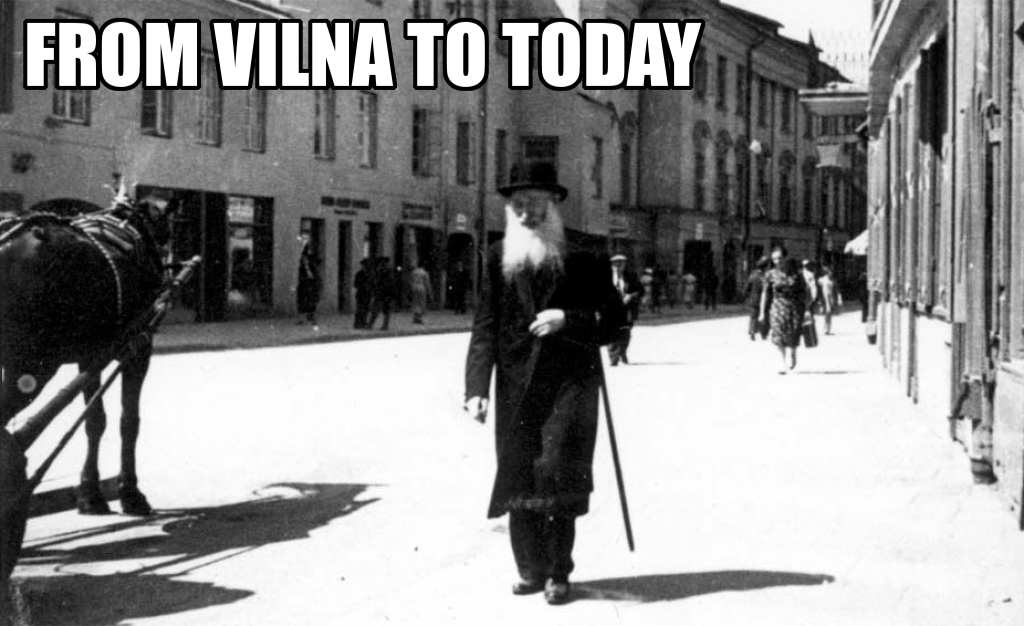

FROM VILNA TO TODAY

There’s a line I once heard that has stayed with me: “We scrutinize our esrogim to make sure they are kosher — but we don’t always scrutinize our middos to see if they are kosher.”

The 25th of Shevat is the yahrtzeit of Rav Yisrael Salanter, founder of the Mussar movement. I have a personal connection to Rav Yisrael Salanter: I learned in Yeshivas Ner Yisroel in Baltimore, which was named after him.

Rav Yisrael was the rebbi of the Alter from Kelm, Rav Simcha Zissel Ziv. The Alter from Kelm was the rebbi of the Alter from Slabodka, Rav Nosson Tzvi Finkel. The Alter from Slabodka was the rebbi of Rav Yaakov Yitzchak Ruderman, the founding Rosh Yeshiva of Ner Yisroel.

In 1983 — the 100th yahrtzeit of Rav Yisrael Salanter — Rav Ruderman made a memorial gathering in the yeshiva. In his address, he told a story about a coincidence. But in Jewish tradition, there are no “coincidences.”

Rav Yisrael Salanter passed away in 1883 on Friday, Erev Shabbos Parshat Mishpatim. There wasn’t enough time to bury him before Shabbos, so the levayah was delayed until Sunday — the beginning of Parshat Terumah. Two parshiyos. Mishpatim and Terumah. Death on one. Burial in the other.

At the funeral, the Alter from Kelm gave the hesped. And he said something extraordinary. It is no coincidence, he said, that Rav Yisrael Salanter passed away on Erev Shabbos Parshat Mishpatim and was buried at the beginning of Parshat Terumah.

Why? Because Parshas Mishpatim is the parsha of bein adam l’chaveiro. Civil law. Damages. Loans. Judges. Workers. Servants. Responsibility. Sensitivity. Integrity.

And Rav Yisrael Salanter’s life mission was to elevate the mitzvos of bein adam l’chaveiro — to make people understand that how you treat another human being is no less important than how you treat Shabbos, Kashrut, or your esrog.

Let’s be honest. We will drive across town for a better hechsher. We will spend hours researching the most mehudar matzah. We will pay a premium for a flawless esrog.

But will we spend that same energy making sure we didn’t embarrass someone? That we didn’t cut someone off mid-sentence? That we didn’t speak sharply to a spouse or child?

Rav Yisrael Salanter saw this imbalance. And he made it his life’s work to correct it.

And that’s exactly what Parshat Mishpatim is about. The parsha opens with the words: “וְאֵלֶּה הַמִּשְׁפָּטִים” — “And these are the laws.”

Rashi famously comments: Whenever the Torah says “eleh” — “these” — it excludes what came before. But when it says “v’eleh” — “and these” — it connects what comes after to what came before.

What came before? The Ten Commandments. Har Sinai. Thunder. Lightning. Revelation. And now? Damages. Servants. Property disputes.

Rashi says: Just as the Ten Commandments were given at Sinai, so too these civil laws were given at Sinai. In other words: Don’t dare think that how you treat your neighbor is “less holy” than how you keep Shabbos. Don’t dare think that business ethics are somehow secondary to ritual observance. In the eyes of God — Sinai is Sinai.

That’s why the Alter from Kelm said it was perfectly fitting that Rav Yisrael Salanter passed away during Parshas Mishpatim. His life was Mishpatim.

But why was he buried during Parshat Terumah? Because Parshat Terumah begins with the Aron Habrit — the Ark that housed the Luchot. And the Alter said: Rav Yisrael Salanter himself was like an Aron Habrit . The Luchot weren’t just in a golden box in the Mishkan. They were engraved into his personality. And it was precisely his devotion to bein adam l’chaveiro that made him worthy of that comparison.

Now let me take you one step further down this chain of transmission. Rav Yechiel Mordechai Gordon, the Rosh Yeshiva of Lomza — a talmid of the Alter from Slabodka — gave a hesped for his rebbi. And he asked a fascinating question. Why does Parshat Mishpatim begin with the laws of an Eved Ivri — a Hebrew servant?

Think about it. The laws of Eved Ivri would only apply when the Jubilee year laws were in force. That wasn’t going to happen for generations. There were dozens of more immediately practical laws the Torah could have opened with. So why start here?

Rav Gordon said something brilliant. Who is an Eved Ivri? He’s not the pride of the community. He’s a thief. And not even a successful thief. If he had money, he’d pay back what he stole. Instead, he’s sold because he has nothing.

He is, socially speaking, at the bottom of the food chain. And yet look how the Torah commands us to treat him. You cannot humiliate him. You cannot assign him degrading labor. You must provide him with the same standard of living as yourself. If there is only one pillow in the house — it goes to him.

The Gemara in Kiddushin says: “Kol hakoneh eved ivri — k’koneh adon l’atzmo.” Anyone who acquires a Hebrew servant has acquired a master for himself.

Is this how you treat a thief? Answer: Yes. Because he is created b’tzelem Elokim – in the image of God. And that, said Rav Gordon, is the Torah’s opening shot in Mishpatim. If even the lowest rung of society must be treated with dignity, how much more so every other human being.

And Rav Gordon didn’t just say this. He lived it. Here’s a story about him. When he was living in New York, in the late 1940s, his nephew was coming from Eretz Yisrael and telegrammed that he would arrive at midnight. Then, due to various delays, he only arrived at 3:00 AM.

And who was standing outside waiting for him? Rav Gordon himself. The nephew was stunned. “You could have left the door unlocked! You could have left a note!”

Rav Gordon shook his head, and said, “I needed to tell you something before you meet my wife. I want you to call her ‘Auntie.’ She’s not technically your aunt, but she takes such good care of me. I don’t want her to feel like an outsider.”

He had waited three hours in the cold, until the early hours of the morning — just to protect someone’s feelings. That is Mishpatim. That is Mussar. That is Torah engraved into a human being.

And let me tell you one more story — this one from Rav Ruderman’s childhood in Minsk. It was Hoshanna Rabbah. The chazzan went up to pray — but the shammes had forgotten to bring him the kittel. The president of the shul publicly berated him. Humiliated him.

Rav Ruderman later reflected: Wearing a kittel is a custom. Embarrassing a fellow Jew is prohibited by the Torah. Which one do you think weighs heavier in God’s pecking order?

But somehow, we get confused. We act as though the kittel is inviolable — and a person’s dignity is negotiable. And that confusion is exactly what Rav Yisrael Salanter came to fix.

The chain is clear: Parshat Mishpatim → Rav Yisrael Salanter → the Alter from Kelm → the Alter from Slabodka → Rav Ruderman → and us. You and me. This is our mesorah, our tradition.

We need to know that Sinai doesn’t end with thunder. It continues every day in how you speak to your spouse, your children, your friends, and your acquaintances. It continues in how you answer an email. It continues in whether you are willing to forego a kittel and not embarrass someone in public.

You can be meticulous in ritual and careless in character — and you will have missed the entire point of Torah. Because the Torah begins its civil code not with the successful businessman, not with the respected scholar — but with a failed thief. Because if you can see the image of God there, you can see it anywhere.

That is the Torah of Mishpatim. And that is the Torah we are meant to carry — not in an Ark of gold — but in the way we treat every single human being who walks through our door.

(This article is based on a parsha shiur given by Rabbi Yissocher Frand)