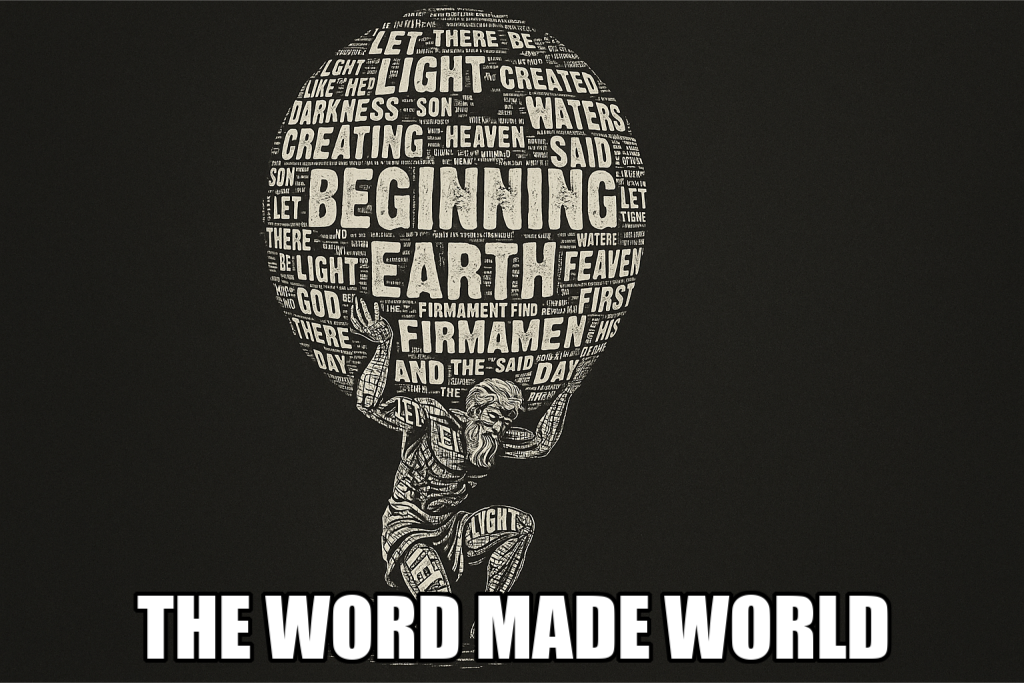

THE WORD MADE WORLD

“Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?”

Those nine words were spoken more than eight hundred years ago by King Henry II of England — and they changed history.

Henry was a brilliant, forceful monarch who ruled in the twelfth century, a time when kings and popes wrestled for supremacy. Henry was determined to modernize his kingdom and bring the Church under royal control, so he appointed his trusted friend and confidant, Thomas Becket, as Archbishop of Canterbury. It was a strategic move — if you put your ally in charge of the Church, then the Church will do what you say.

But the plan backfired spectacularly. The moment Becket put on the archbishop’s robes, he underwent a transformation. The easygoing drinking buddy became a pious defender of the Church’s independence. He resisted the king’s interference in ecclesiastical affairs and argued vehemently for the Church’s right to self-govern. What began as a political trick to subvert the church’s control of England’s national affairs devolved into a bitter feud between the king and his former friend.

Years of confrontation followed. Henry grew increasingly infuriated by Becket’s defiance. And then one day, surrounded by his knights and courtiers, the exasperated king reportedly shouted, “Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?”

Whether he meant it literally or not we simply don’t know. What we do know is that four knights took his words seriously, and they galloped to Canterbury, burst into the great cathedral, and cornered Becket as he was saying evening prayers. When he refused to back down on his anti-Henry stance, they killed him — right there, in the house of God.

The shock reverberated through Europe. Becket was instantly venerated by the catholic church as a martyr. Pilgrims flocked to his tomb in Canterbury, and within three years the pope canonized him as Saint Thomas Becket.

Henry II was blamed for the crime, even though it was unclear if he had meant his words as a royal command. He was publicly very remorseful, and he even performed a public act of penance — walking barefoot through the streets to Canterbury Cathedral and allowing the monks to flog him. His reign survived, just about, but his reputation never recovered.

And what caused it all? Nine words, shouted in anger, set off a chain of events no one could control.

Why am I telling you this? Because I want to convey to you the power of words. The terrifying — and awe-inspiring — power of speech. Words may seem small, they may seem insignificant, but they create realities. A thought is private, but a word is public. Once spoken, it takes on a life of its own.

And that, if you think about it, is exactly how the Torah begins.

The world doesn’t start with God hammering out mountains or carving rivers. It begins with speech.

וַיֹּאמֶר אֱלֹקִים יְהִי אוֹר — “And God said, ‘Let there be light.’”

וַיְהִי אוֹר — “And there was light.”

The Sages in Pirkei Avot (5:1) tell us: בַּעֲשָׂרָה מַאֲמָרוֹת נִבְרָא הָעוֹלָם — “With ten utterances the world was created.”

God could have created the universe in total silence. Guess what: no one was there to hear Him. But He didn’t create it in silence. He chose to speak it into being. Do you know why? Because He wanted to teach us that speech itself is divine. Words are not just tools for communication – they are instruments of creation.

And that’s why, in Jewish thought, everything in existence falls into four categories: דומם (domem) — the inanimate; צומח (tzomeach) — the growing; חי (chai) — the living; and מדבר (medaber) — the speaking.

Only human beings are called medaber. It is our ability to speak words and to communicate via words that elevates us above all of creation. Because our power to use words is what makes us godlike. That is the message of the creation narrative at the beginning of Bereishit.

It is through dibbur — speech — that not only do we bring things into being, but we create meaning, we shape relationships, and we build societies.

The Torah’s first lesson is that the most divine quality within us is not strength, not even intellect, and it’s definitely not emotion — it is the ability to speak, and through our speech, to create.

And that is exactly what happens next in the story of creation.

After the heavens and the earth are formed, after light and darkness are separated, after land and sea and all living creatures are brought into being — God introduces the final element of creation: humanity.

And what do you think the very first task assigned to the very first human being was? Not farming. Not building. Not even praying. No, it was speaking.

וַיִּצֶר ה’ אֱלֹקִים מִן הָאֲדָמָה כָּל חַיַּת הַשָּׂדֶה וְאֵת כָּל עוֹף הַשָּׁמַיִם, וַיָּבֵא אֶל הָאָדָם לִרְאוֹת מַה יִּקְרָא לוֹ; וְכֹל אֲשֶׁר יִקְרָא לוֹ הָאָדָם נֶפֶשׁ חַיָּה, הוּא שְׁמוֹ

“And God formed out of the earth every beast of the field and every bird of the sky, and brought them to the man to see what he would call them; and whatever the man called each living creature, that became its name.” (Bereishit 2:19)

The Midrash (Bereishit Rabbah 17:4) elaborates: when Adam looked at each animal, he understood its essence and gave it a name that expressed its inner nature. He called the ox שור (shor) because it isשורר — it gazes firmly ahead. He called the dog כלב (kelev) because it is כולו לב — “all heart.” And so on.

These names that Adam came up with weren’t random labels, they were acts of perception and definition. By naming each animal, Adam didn’t just categorize creation — he completed it. He transformed physical existence into a moral and spiritual reality.

In that moment, God effectively said to Adam: “I have created the raw materials of the world. Now you must use words to give them meaning.”

And that’s the human mission in a nutshell. To take the formless and give it form, using words. To take the meaningless and give it meaning, using words.

Every time we speak, we do what Adam did: we name, we define, and we shape reality.

If you call someone a failure, then they are a failure. If you call someone a loser, then that’s what they are. But if you call them brave, you help them become brave. One word can destroy confidence or, alternatively, it can awaken courage.

According to Jewish tradition, the world is not only made of words — it is sustained by them. As the Zohar says, בְּאוֹרַיְתָא בָּרָא קוּדְשָׁא בְּרִיךְ הוּא עָלְמָא — “With the Torah — with the words of Torah — God created the world.” And so too, our Torah — our words — sustain the universe.

When our speech is kind, honest, and encouraging, we uphold the fabric of creation. But when our speech is cruel, deceitful, or cynical, we tear it apart.

Henry II’s angry words unleashed chaos. Adam’s deliberate words brought order.

And every generation since creation has had this power. Their words can either be destructive or redemptive.

If there’s one figure in recent history who embodied the creative and redemptive power of speech, it was Sir Winston Churchill.

In 1940, Britain was on the brink of annihilation. France had fallen. Hitler’s armies controlled Europe. The Luftwaffe was bombing London nightly. The United States had not yet entered the war, and the Soviet Union was still allied with Germany. Britain stood entirely alone.

Its army was battered, its navy stretched to the limits, and the Brits were weary and afraid. On paper, the war was over. Great Britain was done for.

But Churchill understood something profound: that even when your weapons are depleted, your words can still win battles. He became Prime Minister in Britain’s darkest hour, and he gave the nation something that tanks and planes could not provide — he gave them words.

In his very first speech to Parliament he said, “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, and sweat.” Words spoken with courage and conviction. Words that inspired a nation.

And then, as the German invasion loomed, he delivered words that would define him, and quite possibly words that saved the free world:

“We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets… we shall never surrender.”

Churchill’s speeches didn’t merely describe courage — they created it. His words turned despair into defiance, and fear into faith. The British people believed they could win because his words drove that belief into them.

Churchill once said, “Of all the talents bestowed upon men, none is so precious as the gift of oratory. He who can speak may command the hearts of men.”

Churchill’s real weapon wasn’t the RAF, or the British Army, or the Royal Navy. It was words. The very same power that God used to create the world and that Adam used to define it. Words.

And if it is true to say that Henry II’s careless words destroyed his world, then we can say that Churchill’s purposeful words saved civilization.

And that brings us back, beautifully, to those words right at the beginning of the Torah: וַיֹּאמֶר אֱלֹקִים יְהִי אוֹר — “And God said, Let there be light.”

When we speak with purpose — when our words are truthful, hopeful, and kind — we bring light into darkness.

That’s why the Torah begins with speech. It’s not just telling us how God created the universe — it’s teaching us how we are meant to live in it.

Each of us is a medaber, a being whose words create worlds. Every blessing, every compliment, every kind greeting, every thank you, every word of encouragement – sustains the creation that began in Bereishit.

God created the world with words. Adam named it with words. Churchill saved it with words.

The question, as we begin the Torah anew, is: What will we do with our words? Because the world we speak… is the world we live in.